The Sound of a Positive Vibration

9/1/2019Was the matronly New Orleans stenographer who founded a French Quarter temple the guru everyone in the 1960s was seeking? At least one follower still believes.

by Michael Warner

The most memorable thing about the Maitreyans was their cry - OIA! - heard in the streets of the French Quarter in late 1960s and early 1970s. The call was pronounced OH EEE AH! - as three distinct words.

For many who heard it, this was a noise, a mystery, abruptly shouted by members of the counterculture and without apparent reason. And then there was the drumming and chanting, going on into the evening.

If the Maitreyans are still remembered by any, it is for these sounds. Who were they and where did they go?

The Maitreyans were a religious group based more or less on Buddhism, but they also incorporated threads of other systems: Hinduism, Catholicism, magic, mysticism and occultism. The group was founded by a woman named Genevieve Wirth Hooper.

Hooper was born Aug. 4, 1921, to Charles P. Wirth and Arabelle Allison, who lived at 1223 Moss St. in New Orleans. Charles made an upper middleclass living as a trust officer at Canal Bank and Trust Company in the Central Business District. Arabelle was a homemaker, and she kept busy raising Genevieve and her younger brother, Charles Joseph. As they grew up, the children attended Catholic school.

In September, 1940, barely at the age of 19, Genevieve married Harold Joseph Hooper, a railroad dispatcher, who was five years her senior. Later he became a mechanic at the Falstaff brewery on Gravier Street.

Over the next 18 years, Genevieve worked as a stenographer and secretary for certified public accounting firms, but in her spare time she nurtured an interest in mysticism and the occult. Immersing herself in these beliefs, Genevieve took on the name Kumi Maitreya. In Sanskrit, “Ku,” means “Sacred Feather,” and “Mi” is an inquiry: “Who?” Maitreya, according to follower Daniel Gordon, was “a name associated in Buddhism with a future Buddha.”

On April 30, 1958, Kumi forever left behind her profession as a secretary and started an “international esoteric school,” that she called Bodhi Sala: the “Temple of the Awakened.” She operated it from her home on Moss Street. In 1968, she opened her doors to the public, and it became the Externalized Ashrama of Kumi Maitreya.

Interest in the ashram was soon boosted by the birth of 1960s counterculture. The Order of Maitreyans grew rapidly as scores of hippies and Viet Nam war protesters flocked to New Orleans for warm weather and the alternative points of view that have always made the city famous.

Kumi expanded her operation into the French Quarter and opened the ashram in an apartment at 627 Ursulines St., near the city’s underground newspaper office, the NOLA Express.

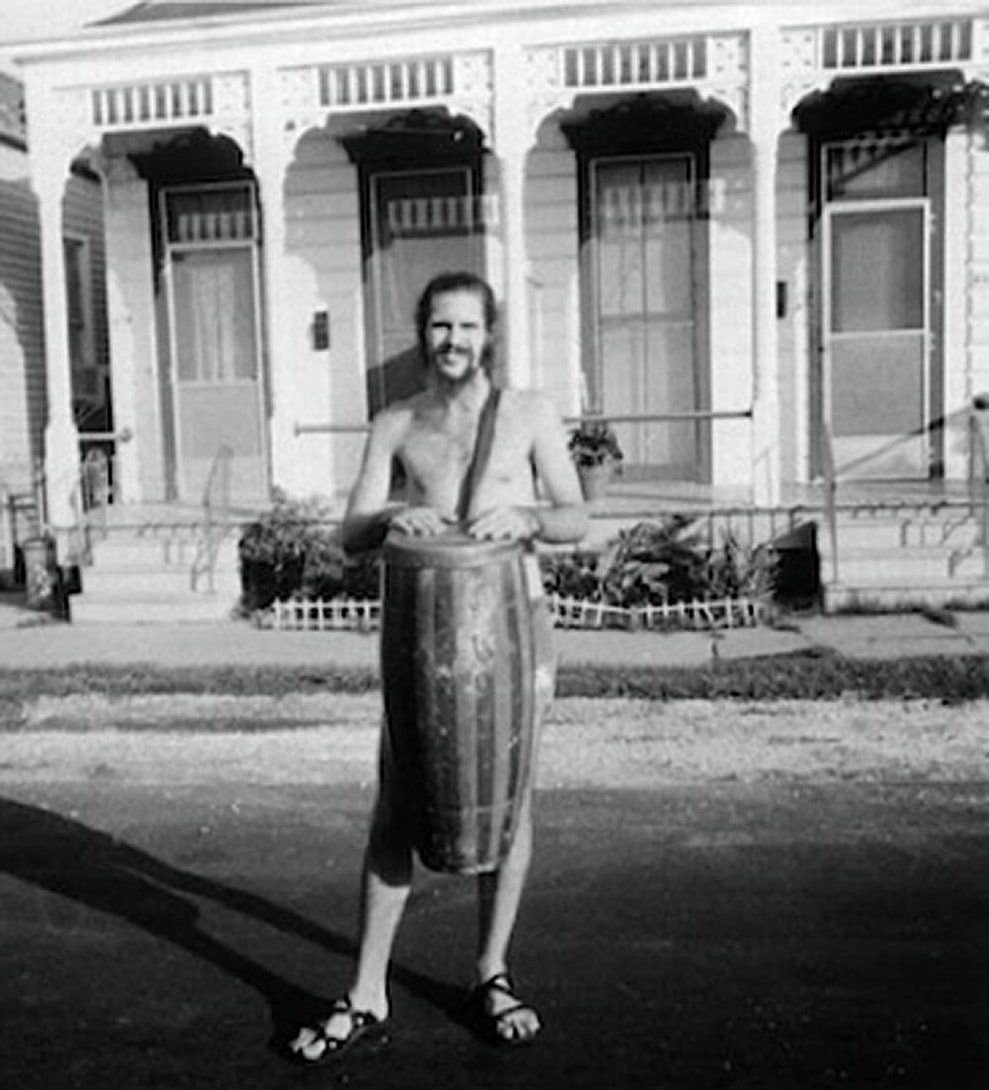

photo courtesy Douglas Gordan

To outsiders, the activities of the Maitreyans seemed to revolve around playing conga drums all day, handing out free LSD to passersby, and randomly calling their mantra, “OIA,” to one another in the street.

But those inside and near the group viewed it as a serious religious order.

According to NOLA Express reporter Darlene Fife, Kumi believed she was “the incarnation of the Buddha. . . . Kumi believed in herself as the avatar, in LSD, and in the U.S. Constitution. She gave each of her followers a new name.”[1]

Maitreyan follower Daniel Gordon, for example, was given the name Kutami. “Kumi also taught the American ideas of enlightenment from the Age of Enlightenment, such as the U.S. Constitution Bill of Rights as a moral code for a free man,” he said recently.

Fife expanded on this idea: “For the Maitreyans, freedom and joy were essential components of daily life.”

The OIA mantra was intended as an expression of this joy. Some have called it “the sound of a positive vibration.” Others have likened it to an expression of femaleness (O), maleness (I) and a blend of the two (A). Kumi herself called it “the natural sound.”

French Quarter artist and former Maitreyan Amzie Adams has a different interpretation of the meaning.

Kumi said you could take whatever you wanted from it. OIA, she got from the Wicked Witch of the West. You know, the little monkeys that would follow her. “OoEeOo. YeoooWum. OoEeOo. YeoooWum.”

That’s what I got from it. So, OIA, man!

One of the few Bodhi Sala books left in existence, according to Amzie. He keeps his in a protective plastic folder, inside a plastic bag.

Adams told the story of how he joined the Maitreyans.

I met these two girls and they took me to their house and they kept me for two weeks. And they said, Oh, you’ve got to meet Kumi. They were Bodhi Sala. So they took me. She looked like this little old lady from Metairie. Like a Yat from Chalmette or something. All white, white hair, she just seemed like everybody’s mom or something. And I thought, you’ve got to be kidding, man. She didn’t fit my guru mold.

But Adams, even now, is convinced Kumi was everything she claimed to be. He had gone on tours around the nation to meet gurus and mystics in other cities. Adams was unimpressed by them. “They were kind of like a cult of personality. To make money or something.” But Kumi “was the real deal. I traveled all over the world looking for the real deal, and the real deal was at home.”

One day they went to a Festival of Life celebration that the Maitreyans held every so often at Audubon Park.

I started dancing, and I wasn’t doing drugs or anything. I was just dancing, basically. And all of a sudden, I started hallucinating like crazy. I hallucinated a double black circle line. Other lines between two circles. And in between was a big star. And in the negative areas of the star were all the colors, like red, orange, blue, green.

And the colors were pulsating in and out, and the black lines in the circle were like moving and dancing. And inside of all that, inside the star was a black-and-white motion picture. And in the black-and-white motion picture, I saw me, kneeling down, and someone strangling me.

I thought, “Man, this is horrible. It’s really horrible.” And I keep hearing this voice, like the voice of God or somebody. And it kept going, “Time, space, energy and matter are one. They are not on a continuum as you perceive them.” Over and over again. While this visual is going on. It went on for an hour.

About two weeks later, Adams went to a Bodhi Sala ritual. Kumi was ordaining new members and giving them Maitreyan names.

So I’m sitting way in the back, you know, always being very critical, always looking at the whole thing. . . . But every time somebody goes up there, she says something to them, and they start looking like they stuck their finger in a light socket. They start hoppin’ around and screaming and yelling, and going into convulsions. They’ve got to drag them out. You know?

Adams was skeptical.

I’m like, “Really??” Well, if she calls my name and I go up there, I’m not going to do none of that crazy crap.

So finally she calls my name, you know? My old ex-Marine comes out. “OK, lady from Metairie. We’ll see about this. I ain’t going to be flipping out. You can just forget that.”

So I get there, and she looks at me. And she gives me what they call the Lama Kumi voice. She’s got the Lama Kumi voice. She tells me, “Son, kneel down.” So, OK, I can do the kneeling thing. I’m a Catholic. I know. So I kneel down.

And guess what she does — she grabs her hands and puts them around my neck. And she goes, “Time, space, energy and matter are one. Not on a continuum as you perceive them.” And she goes, “You little jerk, remember that? In the park two weeks ago? Remember that? I can do that at any time. All I got to do is look at you. I can come into your dreams and do that.”

And then she put her hands around my neck. I started feeling like I stuck my finger in a light socket. I started getting shocked and rolling around in a circle. They had to drag me out. And my heart was going [trill]. I’m a healthy young guy and that 60-year-old old lady just fried me, man.

Artist Amzie Adams describing Kumi's commanding voice.

The Maitreyans were also active in projects where they felt the city left gaps in the social safety net. In 1971, they became the first to organize off-street accommodations for cash-poor Mardi Gras visitors to sleep, eat and revel.[2]

Not everyone viewed the Maitreyans as a benevolent group, however. On multiple occasions, they had run-ins with the police.

For example, in March, 1972, Kumi was arrested for an activity that one waggish reporter called DWP - driving while preaching.[3]

Daniel Gordon was in the car when it happened.

That was a hoot. What it was, is that after our evening gathering, very often afterwards, we piled into her car. We had to shut down any drumming and chanting by 10 o’clock. And we’d all be worn out then anyway. And so we’d then all pile into her car. A blue Ford Fairlane station wagon. And then we’d drive around town because we’d check on these subtle energies. It was interesting, the things you could see at night, driving around New Orleans.

And we’d make that turn, and we’d all be going, “OH EEE AH!” as we’d make the turn. We’d make the connection there and we’d drive up the other end. And so [the police] saw us doing that, and they decided to say, whatever they decided to put up there, what was it? Driving unsightfully, or whatever it was they were talking about. I don’t know. But basically we were doing what was known as a religious ritual. And the street was empty. It was not like there were other cars.

That evening, Kumi chose to drive in circles around the neutral ground at the bottom of Esplanade Avenue, near Decatur Street.

The police arrested Kumi on a charge of reckless driving.

Weeks later, she told the traffic court judge that when arrested she was performing a “brief religious ceremony to safeguard the city through the night by the conscious expenditure of energy.” As a strong believer in the U.S. Constitution, she threatened to sue the city in Federal court, arguing that the arrest was a violation of her religious freedom.

The police testified that Kumi had circled the neutral ground “five or ten times and ran a stop sign every time.” But witnesses under oath said that Kumi circled the neutral ground only three times, because that number had religious significance.

The matter became even more complicated, much to the glee of the press, when Kumi refused to allow her court-appointed attorney to speak for her during the trial. Kumi told the judge, “I’m looking at all you dudes with respect, but I’m not about to sign over the proxy of my mouth to a lawyer.”[4] All the while, up to 30 Maitreyans sat in the courtroom to watch the proceedings.

Judge Lambert J. Hassinger apparently found Kumi’s witnesses credible and her argument sympathetic. Or perhaps he saw this as an intractable mess he didn’t want to deal with. In any event, he dismissed the case against Kumi.

The Maitreyans continued their activities in the French Quarter for a few years but in the mid-1970s began to fade away. Daniel Gordon explained it:

Eventually the library was sold off. It was a considerable library, too. Every kind of occult book you could think of. There were a few people that continued to attend. And I lost track of them on account of, I went off to college. . . . and then I went off trying to make a living. And that is what I think it was. The Viet Nam war was over, the whole culture had changed. It had moved away from that whole love and peace thing. That is where the change happened, really.

Kumi’s husband, Howard, passed away in 1981, and some years later she remarried one of the members of the ashram. Kumi died peacefully of natural causes on May 26, 1995, at 1223 Moss St., where she had resided for her entire life.

Today the Maitreyans are scattered across the country. A few still live in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast, though many have moved elsewhere.

But if you listen on a summer night on Ursulines Avenue, you might still imagine an echo of OH EEE AH! and the beat of drums.