Tennessee Williams and the French Quarter

Tennessee Williams, 1965, photograph by Orlando Fernandez, Library of Congress

10/23/2020A look at the famous playwright's complex and lifelong relationship with the neighborhood where he brought "A Streetcar Named Desire" into being.

- by Richard Goodman

On a cold February day in 1983, I was at the entrance of the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on Madison Avenue at 81st Street. I was there to see Tennessee Williams.

He had died a few days earlier at the Hotel Elysée in New York.

I opened the heavy door to the respectable-looking five-story building. I was met by a young man in a dark suit. He looked distracted.

“Are you here to see Mr. Williams?” he asked, looking away.

I said yes, I was.

“Take the elevator to the second floor.”

I walked out of the elevator, and another young man extended his arm in the direction of an almost-empty room. A few people were there, less than I expected. I walked to the far side of the room, and there he was. He was in a casket, dressed in a coat and tie, arms folded over his chest.

He looked so small. It didn’t make sense for the colossal things he’d done that he be so diminutive. I leaned closer. I could see the make-up on his mustache caked at the bristles’ ends. They could’ve done better than that, I thought. I also thought how he would have relished writing about this small indignity.

His eyes were closed. The cause of his death would have darkly amused him, too. Or confirmed his clear-eyed vision of the absolute indifference of death. It will come when, and how, it will come. He had choked on a bottle cap. That cause of death has since been contested, but, really, who cares. He was dead.

I was the only one next to his coffin.

I spoke to him.

“Tennessee, thank you for everything you gave us. Thank you for Streetcar. Thank you for Glass Menagerie. Thank you for being brave. Thank you for everything you wrote. You were a great artist.”

I felt less secure in the world now that he was gone.

“Goodbye,” I said.

I absurdly thought he might reply in his famous deep, lilting cadence.

I turned and walked away from this momentous death.

On December 28, 1938, Thomas Lanier Williams came to the French Quarter in New Orleans for the first time. He was not aware that Tennessee Williams was waiting there to greet him.

He was 27 years old. This was six years before The Glass Menagerie opened on Broadway and made him famous. Nine years before A Streetcar Named Desire astonished and overwhelmed Broadway. Years before those plays created the “catastrophe of success” that he wrote about so eloquently in The New York Times.

Jessica Tandy, Kim Hunter and Marlon Brando in the original stage production of "A Streetcar Named Desire," 1947. Library of Congress

It would be years before that malady descended upon him, stripped him of his anonymity and penury and made it much more difficult for him to avoid, as he described it, “the vacuity of life without a struggle.” The new struggle became dealing with a lack of want and with the false god of fame, with success - what William James called “the bitch-goddess.” Williams was much less successful in dealing with the catastrophe of success, as anyone who reads about his later years can tell.

In 1938, though, he was an obscure, struggling playwright who was about to discover a world he didn’t know existed, where he would feel completely at home - artistically, emotionally and physically. It’s exhilarating and satisfying to read about those early years in the French Quarter when he was unknown, struggling, insecure and, for the most part, happy.

This is Williams’s entry in his notebook about the first day:

How Strange!

Immediately after the above entry I find myself reporting that here I actually am in a completely new scene – New Orleans – the Vieux Carré. Preposterous? Well, rather! Somehow or other things do manage to happen in my life….

I am delighted, in fact, enchanted with this glamorous, fabulous old town. I’ve been here about 3 hours but have already wandered about the Vieux Carré and noted many exciting possibilities. Here surely is the place that I was madefor if any place in this funny old world.

It’s hard to overestimate the influence New Orleans, and particularly the French Quarter, had on Tennessee Williams. Everyone knows about A Streetcar Named Desire, his most well-known play, set near the French Quarter. But the importance of the neighborhood in Williams’ life goes far beyond the setting of an iconic American play. The Quarter was his artistic birthplace, his mother, his father, his lover and his muse.

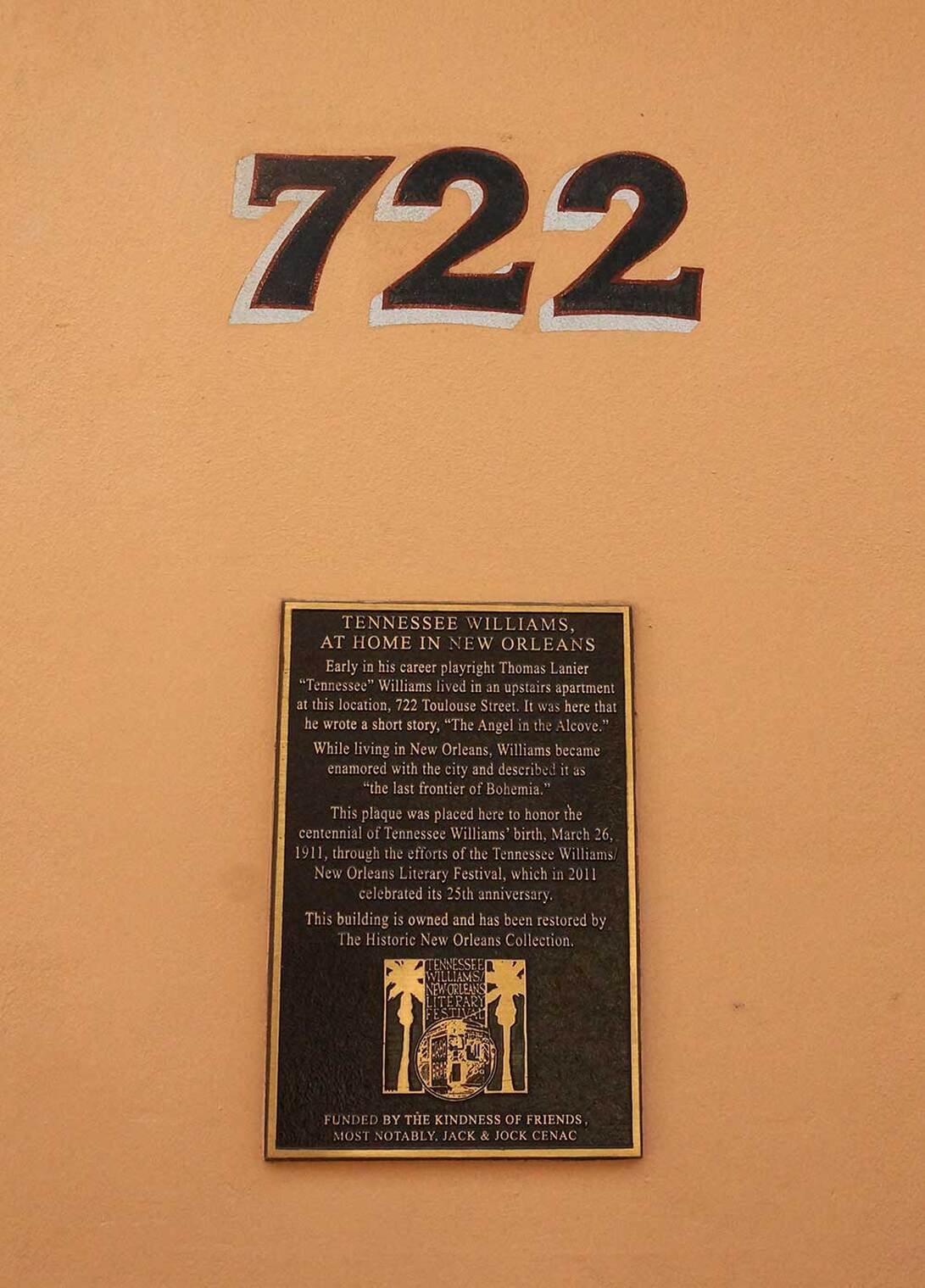

According to Lyle Leverich in his excellent book about Williams’ early years, Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams, Williams’ first night in the city was spent in a hotel on Lee Circle close to the Garden District upriver. The next day he moved into a cheap hotel on 431 Royal Street, which runs through the heart of the Quarter. This address is on the same block on Royal as Brennan’s Restaurant. He lived there for a week, then moved into an attic garret at 722 Toulouse, between Royal and Bourbon.

431 Royal Street, Williams first New Orleans residence.

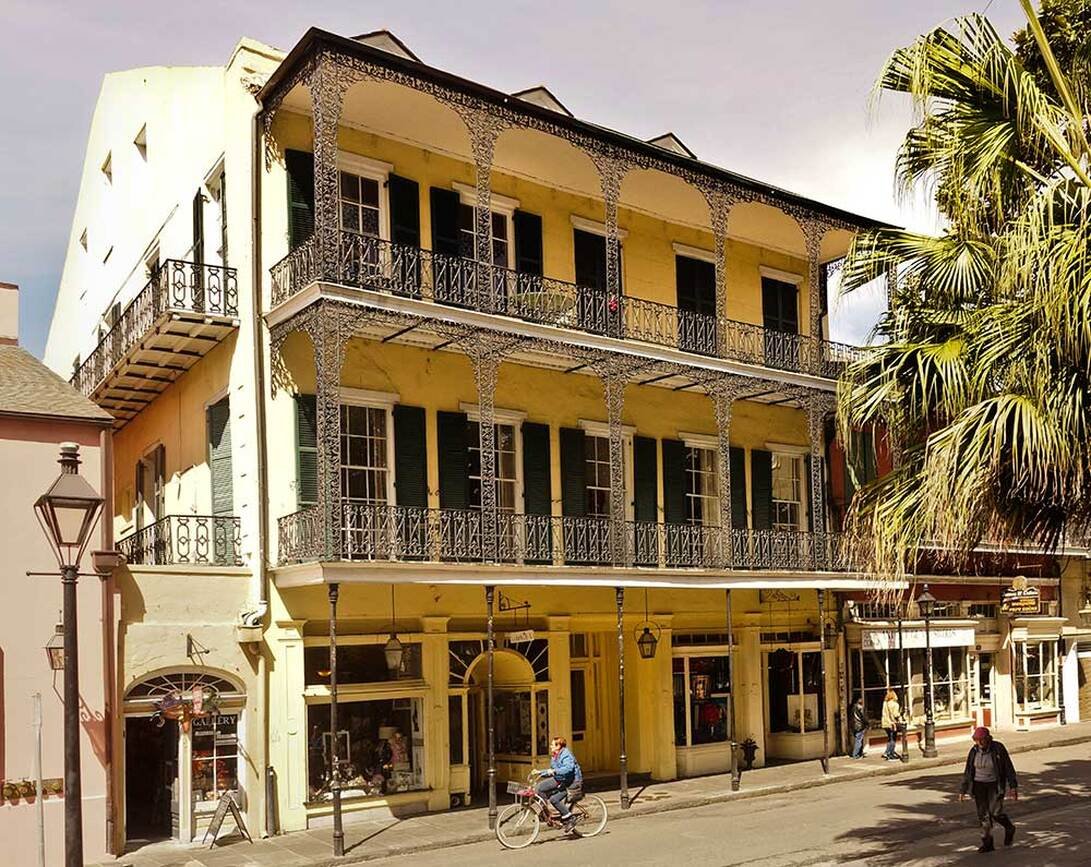

That building exists today, and there is a plaque signifying his stays. He lived there more than once. The Historic New Orleans Collection bought the building, the man behind the information desk told me, and, in refurbishing it, eliminated the attic where Williams spent his first days in the Quarter. The building is not accessible to the public. It contains offices for NOHS. Well, you can read the plaque and look up and imagine.

The French Quarter delighted and stunned Williams, who had been raised by an often-absent father and a puritanical mother in St. Louis. (He was born in Mississippi, but the family moved to Missouri.) As Leverich puts it, the Quarter’s hedonism “both shocked and intrigued him, the classical Apollonian disciplines gone to Dionysian orgiastic rites. At once, an inner and lasting conflict was set up.

Photograph of Edwina Williams, Rose Williams, and Thomas Lanier Williams / ca. 1915. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Tennessee Williams Family Papers, acc. no. 2006.0385.1

In time, Tennessee Williams would come to call himself a "rebellious Puritan," and looking back upon the impact of New Orleans he would say that there "I found the kind of freedom I had always needed. And the shock of it against the Puritanism of my nature had given me a theme, which I have never ceased exploiting.”

On New Year’s Day, 1939, he wrote, “What a nite! – I was introduced to the artistic and Bohemian life of the Quarter with a bang! All very interesting, some utterly appalling…”

In other words, his experience in the French Quarter was complex. The Quarter still has the ability to shock people, especially on unchecked Bourbon Street, and especially if they’ve never encountered anything like it. Imagine what it was capable of doing 80 years ago to a conservative, pent-up young man from St. Louis, Mo.

After he had absorbed some of the initial shock, he wrote a letter to his mother on January 2, 1939, describing his impressions of the French Quarter:

“The Lippmann’s friends [Knute Heldner and his wife, Colette, both painters] have been lovely to me. They invited me to a New Year’s Eve party which lasted till day-break and traveled through about half-a-dozen different homes or studios and I met most of the important artists and writers….

“I’m crazy about the city. I walk continually, there is so much to see. The weather is balmy, today like early summer. I have no heat in my room – none is needed….”

722 Toulouse Street, now part of The Historic New Orleans Collection complex

He soon moved to 722 Toulouse.

What did he do to make ends meet? His landlady at 722 Toulouse opened a restaurant on the premises, for which Williams wrote a slogan, “Meals in the Quarter, for a quarter.” Williams served as the waiter for this short-lived venture. The interlude at 722 Toulouse was not without its farcical aspects either. In early February, he wrote to his mother:

"As I’ve probably mentioned, the land-lady has had a hard time adjusting herself to the Bohemian spirit of the Vieux Carre. Things came to a climax this past week when a Jewish society photographer in the first floor studio gave a party and Mrs. Anderson [the landlady] expressed her indignation at their revelry by pouring a bucket of water through her kitchen floor which is directly over the studio and caused a near-riot among the guests. They called a patrol-wagon and Mrs. Anderson was driven to the Third Precinct on charges of Malicious Mischief and disturbing the peace. The following night we went to court—I was compelled to testify as one of the witnesses."

Thus began a 45-year association with the French Quarter for Tennessee Williams.

By my reckoning, Tennessee Williams resided at the following addresses in the French Quarter:

431 Royal Street, 1938

722 Toulouse St., 1939

708 Toulouse St., 1941, where according to Tennessee Williams and the South by Kenneth Holditch and Richard Leavitt, “he was evicted as the result of an incident involving sailors.”

538 Royal Street, 1941

722 Toulouse St., 1941, for a second time

710 Orleans Avenue 1945-6, where he lived tempestuously with Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzalez.

632 ½ St. Peter Street, 1946-47, which Holditch and Leavitt say he called his “favorite apartment.”

1014 Dumaine, 1962 - on and off - until his death in 1983.

He not only lived in the Quarter at various times in his life until his death in 1983, he also would visit New Orleans, staying at the Hotel Monteleone, for example, or the Pontchartrain Hotel. It’s hard to keep a faithful reckoning of his comings and goings.

For me, where Williams lived in the Quarter has far less meaning and consequence than what he did and learned. New Orleans was Williams’ Paris of the 1920s. (When he at last did go to Europe it was Rome that captivated him, not Paris.) New Orleans, was his soil and sun. He grew and flourished. He left the Quarter often and returned to it faithfully, even after long absences. He learned in New Orleans about the vacuity of life without a struggle. And struggle he did in the Quarter when he was young.

708 Toulouse St., where Williams lived in 1941. According to "Tennessee Williams and the South" by Kenneth Holditch and Richard Leavitt, “he was evicted as the result of an incident involving sailors.”

Every fan of the writer has their own version of Tennessee Williams. Especially if they live in New Orleans and most especially if they live, or have lived, in the French Quarter. Is your Tennessee William the man who, without living in the French Quarter, would never have written A Streetcar Named Desire? Never mind that the play is set outside the Quarter (despite what Mitch says). The setting of the play, as described by Williams, is “a two-story corner building on a street in New Orleans which is named Elysian Fields.”

Specifically, the building is number 632. This is the Marigny, not the French Quarter. But never mind. I would guess Williams couldn’t resist using the name Elysian Fields, no matter where it is. Yes, never mind, because in the collective consciousness of the world, A Streetcar Named Desire takes place in the French Quarter.

Is your version of Tennessee Williams the prowler of streets, the gay man just emerging from a mid-twentieth-century closet, who cruised the Quarter and brought young men to his room for fleeting moments of desire? When he returned to the French Quarter in 1941 after a two-year absence, he made an entry in his notebooks that addressed that moment:

“The cold and beautiful bodies of the young! They spread themselves out like a banquet table, you dine voraciously and afterwards it is like you had eaten nothing but air.”

I will leave it to others to describe the particulars of his nocturnal wanderings.

Photograph of Tennessee Williams at Marti’s Restaurant / ca. 1982. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Kemper Brown, acc. no. 2015.0124.

My Tennessee Williams is the man who was liberated and inspired by the French Quarter and who struggled there while becoming the playwright he was meant to be. As a writer, as any kind of artist, you need models and masters. How do you live the life you need to live? How do you keep going when it all seems fruitless - not to mention when you’re flat broke and your work is being rejected? You can look to Tennessee Williams. You can look to him for the two essential things you need to have to be a writer: courage and resolve.

Reading his Notebooks and his letters, you hardly ever encounter - maybe never - a complaint from him. And he certainly had plenty of reasons to complain. The only time he comes close is when he admonishes himself for not writing as well as he can.

He works without fail, no matter what the situation. If he’s been out carousing and cruising, you’ll still find him at his desk early that morning working away. If he hasn’t a dime in his pocket - a predicament he often found himself confronting in the times he lived in the Quarter - then he hocks his beloved bicycle, his only suit, or even his typewriter.

His mantra, the words he wrote again and again at the close of his entries in his Notebooks through the years is En avant! Forward!

538/540 Royal, on the corner of Toulouse.

Williams left New Orleans after a few months in 1939 to travel to California. He lived at various places, including Key West, his other refuge, writing and struggling, in the interlude. He returned to the Quarter in 1941. On September 11, 1941, he wrote in his Notebook,

“The Second New Orleans Period here commences…. He [Williams] still looks for sanctuary.”

The cost of living? “Paid a week’s rent--$3.50.” On September 14 he notes, “Went to Gluck’s [German restaurant, now gone] and had a 30ȼ Turkey dinner—good.”

He wrote, always, and the Dionysian pull was there: “This life is all disintegration here in N.O.

All the old bad habits and more.”

By then he was completely out to himself, and was cruising the streets and the clubs in the evenings. But always—always—up the next morning and at his desk. He bought a bicycle and took trips of considerable length—to Bay St. Louis and back, for example. And he struggled.

720 Orleans Street, in the foreground.

A plaque on the wall of 632 1/2 St. Peter identifies the building as once being the residence of Williams.

On October 17 1941, he wrote in his notebook, “I am flat broke—stony—literally not one cent…Guess I’ll have to sell a suit tomorrow. Hate to. But I do love to eat….Rent over due 3 or four days…Well—let’s hope a gift arrives in the mail. En avant!” Three days later he wrote, “Drank half a pitcher of water to relieve my hunger.” By November, he was gone, back to St. Louis, with $25 from his mother for transportation.

But then, four years later, in 1945, everything changed. On March 31, The Glass Menagerie premiered on Broadway. It won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award as Best American Play. And the unknown Tennessee Williams would be unknown no more.

He returned to the French Quarter in December, 1945 and moved into an apartment at 710 Orleans Street, just behind St. Louis Cathedral. He moved in with Pancho Rodriguez y Gonzalez, a domestic situation that was often chaotic and fraught. He began writing the play that would come to be A Streetcar Named Desire there. That play premiered on Broadway December 3, 1947. Just nine years after he arrived in New Orleans for the first time as a young man, lost and searching.

In 1962, Williams bought a house at 1014 Dumaine. We have Dick Cavett to thank for being able to see inside that house. In 1974, Cavett and Williams were by coincidence both in the French Quarter. Cavett scored an interview with Williams, which, thanks to YouTube, you can view.

1014 Dumaine Street, the French Quarter building that Williams owned until he died.

The interview takes place mostly in the courtyard of the Maison de Ville on Toulouse Street, close to 722 Toulouse where Tennessee first stayed when he arrived in the Quarter 35 years earlier. The previous day, Williams allowed cameras into his Dumaine Street home, and you can see his bedroom. Williams and Cavett also take a carriage ride through the Quarter and walk a bit in Jackson Square. Williams talks about his early days in the French Quarter, including telling that story of his disgruntled landlady at 722 Toulouse pouring scalding water on loud party-giving tenants below her and everyone being hauled off to night court.

Williams also tells Cavett that he would like to live again in the Orleans Avenue apartment he occupied in 1945-6 where, he says, he wrote most of A Streetcar Named Desire. The writing of A Streetcar Named Desire has come to have the same brand of mythology as places where George Washington slept. Not too long ago, I was on the terrace of the Pontchartrain Hotel on St. Charles and was informed that this was where Tennessee Williams wrote A Streetcar Named Desire.

Tennessee Williams died in New York. Now, we have an annual festival in the French Quarter to honor his legacy. And, of course, we will always have the plays. They are immortal.

“America has only three cities,” Tennessee Williams once famously said. “New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.”

There is still much more to be written about Tennessee Williams’ love for and connection to the French Quarter.

I suspect there always will be.

Tennessee Williams residence in mourning, 632 ½ St. Peter Street / George E. Jordan, photographer / ca. 1983. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1995.7.207.