Interview: John Warner Smith, Poet Laureate of Louisiana

The state's former Secretary of Labor is now its Poet Laureate. In lieu of hearing Smith speak at the Tennessee Williams Fest this year, we offer this profound and insightful interview.

- by Skye Jackson

I walked into John Warner Smith’s office for an interview but left with a lesson.

Smith, a public servant turned poet, recently became Louisiana’s Poet Laureate. He is the first male African-American poet to hold the prestigious position.

John Warner Smith

It did not take long to sense his urgency about education, particularly the education of Louisiana’s disenfranchised black youth. Smith points to a large black and white photograph hanging on the wall. The picture shows a classroom filled with at least 30 or more black, kindergarten-aged children gathered for a lesson. Two adults, a pastor and his wife, stand smiling at the chalkboard. The year is 1957.

“Five points if you can find me,” Smith says, pointing up to the array of brown faces lighting up the room. I step into that classroom with them, sit down and listen.

After Smith and I discuss poetry and books, he prints out an excerpt from Booker T. Washington. Smith taught the essay in his African-American literature classes and is adamant that I read it.

"Five points if you can find me," Smith says.

“Read the first line,” he says. I begin to recite, much like I imagined Smith and his classmates once did. The words hang in the air like a hymn.

“The world should not pass judgment upon the Negro, and especially the Negro youth, too quickly or too harshly. The Negro boy has obstacles, discouragements, and temptations to battle with that are little known to those not situated as he is. When a white boy undertakes a task, it is taken for granted that he will succeed. On the other hand, people are usually surprised if the Negro boy does not fail. In a word, the Negro youth starts out with the presumption against him.”

“Whew,” I say.

“That’s powerful,” Smith responds. “From 1901. Can you believe it?”

The words zing through the office, sudden as a sting, even though they’d been written almost 120 years before. The passage has opened a door. Smith begins to speak of the power of lineage – the impact of ancestry. I begin to see my own path taking shape, buoyed by words left by other writers of color. They contain the knowledge I need. The strength woven into the fabric of my soul. I’m silent, letting the words linger.

“I try to instill this in my students,” he says. “That’s all a part of knowing who you are. It’s important because they left you something. Something that enabled you to be right here, in this room, listening to me speak and pursuing a big dream.

“It might not have been much, you know. But it is enough to put you right here. Now you have a responsibility, not just for your children, for your family, for your community, for your race to build something that those who come after you can use.”

I leave Smith’s office feeling a sense of renewal and a shared sense of urgency as well. The drive to create. The impulse to do. Smith’s words were a reminder that I must keep my own candle lit so that one day others will be able to make their way out of darkness.

Smith shared his passions, poems, upcoming projects and artistic motivations and the initiatives that he plans to implement as Louisiana’s Poet Laureate.

Q. What inspired Muhammad’s Mountain? What was it about Muhammad Ali that captivated you enough to devote an entire book of poetry to him?

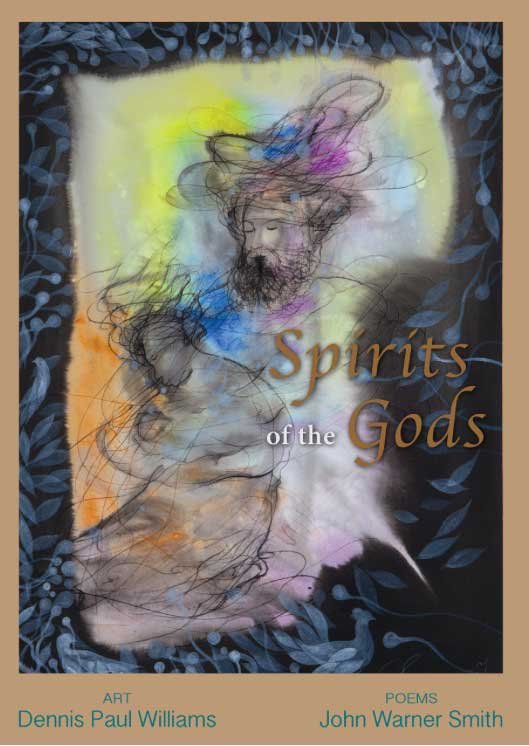

I wrote my first poem about Muhammad Ali the weekend of his death in June of 2016. I was actually working on another book, The Spirit of the Gods. That (Ali) poem is in that book. A couple of years later, I was just thinking about Ali and wondered whether there had been any poems written about him. I went online and couldn’t find but maybe a handful of them and at that point the idea of the book was born. Why not a book?

Ali had been a personal hero of mine since I first began to follow his fights, his opposition to the Vietnam War and his refusing to be inducted into the military because of his religious convictions as a Muslim. But he was someone whom I admired all of my life. I was close to him in that sense. So that’s how the book came about.

I contemplated your book in terms of the way that we as a society tend to glorify celebrities and sports stars – particularly those that are complex, as Muhammad Ali was, and more recently, the late Kobe Bryant. How do you think that poetry speaks to the way that we idolize these figures?

They are sort of larger than life figures – iconic. There’s also this very personal connection that we make from a distance. I never met Ali. I never met Kobe Bryant. For example, when I was in junior high school, I was one of five black students integrating public schools here in Lake Charles. And I caught hell that year. I was the darkest of the five. Two boys. Three girls. I was spat on, called names, just humiliated. As I was going through that struggle, that challenge, Ali was facing up to the government. And I said man, that’s what courage is.

And so we made the connection at that point. I mean, I had known him as a young fighter – not known him, but seen him – his first championship fight against Sonny Liston. By then, his rematch, which he won as well. He was young. He was almost like a big brother, little brother thing. I didn’t have a big brother that I could look up to. And it started there. There has to be that personal connection.

With a guy like Kobe, he was much younger of course. But he’s a year older than my son. So I kind of see him as a son to me, not a brother.

Q. What initiatives do you hope to implement during your tenure as state Poet Laureate? How do you hope to effect change?

Editor's note: This interview took place before the COVID crisis.

Poet Laureate travels the state as an ambassador of poetry, building awareness of the importance of poetry and how it enriches our lives. The Louisiana Endowment of Humanities (LEH) is a non-profit organization that coordinates my work. It helps facilitate scheduling and the work that I do. I’ve done at least 10 readings since August. I have another four or five scheduled. I believe in being as accessible as I can. I haven’t turned anyone down (laughing). No matter how small the event.

I’m working with the LEH right now on a grant which, if we’re successful, will enable me, beginning next year, to reach out to some of the rural parishes and school districts in Louisiana to do poetry workshops with high school students. I think being the first African-American male poet laureate I bring a different face to the office. I bring a unique perspective as a black male poet and a personal story that’s different than any other poet laureate.

Growing up in a small community, poor. The child of a teenage mother. Living in the Jim Crow South. Attending segregated schools and then at some point really breaking down barriers to integrate schools. I can talk. I can bring experiences to poetry that no one else can.

We’re targeting parishes like East Carroll, Morehouse, Tensas, Concordia. Places that typically the poet laureate will not go to. And schools that have some challenges. Students that are facing academic achievement challenges – the majority of them African-American enrollment, probably economically disadvantaged students.

Q. I read that you “began writing poetry while building a successful career as a public administrator and banker.” What was it about that particular time in your life that propelled you into the world of poetry?

Well, I struggle with trying to pinpoint the exact point in my life when, I like to say, poetry discovered me. But it was sometimes in the mid-90s and at the time I was living in Lafayette running a parish government. I was actually planning the consolidation of the city and parish government, which I eventually led as chief administrative officer for the first year. This was long before my banking days.

So, even during those years, I put on the face of a public administrator – a very public guy. I’d go into city hall every day doing my thing. At night I’d go home and write. I’d read poetry. I did that for a number of years. Just kind of showing the world this persona of one person and then being another.

I left Louisiana for a year, went to Florida and came back. I started a career in banking. Even in those five years as a banker, I’d write. I’d travel the state. These poems would just be in my head. I was writing poetry then. Still I didn’t take it seriously. It was something that I was enjoying doing. And then in 2003 I was accepted to the Callaloo creative writing workshops; but that year I had to pass because my mother was very sick so my first year at Callaloo was 2005.

By then I had left the bank and I was Secretary of Labor for Louisiana. And my first year as Secretary of Labor, 2005, I put in a request to the governor to take a couple of weeks off and write poetry. The Chief of Staff said, ‘Yeah. Yeah. Go do it!’

That was in May, 2005, before Katrina. So I did my first year of the Callaloo as a fellow. I skipped the second year. I skipped ’06 because I was in the middle of the recovery process. But I went back in ’07 and ’08 and did three years at Callaloo.

I was the old guy at Callaloo. There were much younger people. People like you studying at MFA programs. This young lady – I forget her name – but she was probably 19 or 20 years old. We were leaving the workshop. It might have been the last couple of days of a two-week program.

And I said, ‘Man, I’m too old for that.’ I’ve got a full-time job, mortgages, bills to pay. I can’t quit work and go write poetry. So she mentioned that UNO had a low-res program. So I looked into it and I said, ‘You know, I think I can do that.’ I entered that program the following year and did a couple of summers abroad, online work, and it worked out.

The abroad stuff … was unforgettable. The first time I went to San Miguel. The second summer, I went to Scotland. Edinburgh, and my wife came along. We got to see London, spend some time there. It was nice. Mexico, San Miguel, Mexico City.

So, from the MFA program, I had my manuscript. I had a full book. The manuscript only required 25 poems. John Gery worked me to death revising those poems. So I ended up with a pretty strong manuscript.

And then after I graduated, I said, ‘Well, let me see.’ I went and pulled out the other poems and began working on a full-length collection. So A Mandala of Hands was born from that. The rest is history.

Q. I’ve heard that poetry is a jealous mistress. How do you find the time to write as you balance your career and your duties as Poet Laureate? Do you adhere to a certain schedule?

The good thing is that my manuscript is … in the publisher’s hands now; so I’ve got that done. Actually it was done a while back but he had a little personal setback. He has a small press. It’s based in North Carolina – called Mad Cap. They do great books. He lives in Cambridge, Mass. He had some health issues. So the last quarter of last year he wasn’t ready for it so I started writing more poems and tweaking more stuff.

The initial structure was that it would be a book of selected poems already published in other collections and some new poems on race. But then all of the poems deal with race. I don’t know if it started last fall – I decided to throw all the new selected stuff out and just do a book of new poems. The book will be published when we commemorate the (40th) anniversary of the Atlanta Child Murders. I have about 20 poems dealing with just that. I got that done and it really freed me up to focus on poet laureate work.

What I find most challenging is that I run a non-profit, although it will probably be my last year, thinking creatively and teaching. I do my best writing when I’m not teaching. You’ve got 14 weeks of a semester in which you’re just focusing on… teaching. You have to find that space to create something fresh, and it’s hard for me.

Last semester I taught African American lit. Teaching that gives me inspiration. Starting at the end of this month, I’ll be teaching a poetry workshop at Baton Rouge Community College once a week. I find that teaching liberates me. It’s kind of a spiritual thing for me. I don’t find it that much of a challenge. I manage to juggle it all. But I would like to begin to think about a new writing project.

Q. You often credit the brilliant poet Tracy K. Smith for helping you to see a poem as something “becoming” rather than being. I’m so intrigued by this idea – that the poem exists constantly within a state of flux. Do you believe that a poem is ever complete? Or is that state of “becoming” perpetual?

I do think that it’s a process. I start off with a line – or I may have a picture in my head; an image or thought. Here’s an example. A couple of new poems that are in the book, a couple of my favorite poems, one of them, “White Lightning,” was a finalist for the James Hearst Prize but will be published in the North American Review. The other, “Artifacts,” was accepted by the Southern Review.

Anyway, those poems were born by me walking around my offices here, walking around downtown. I stopped in the library. There’s a little one across the street – a temporary library. The new library is being built downtown.

For “White Lightning” I walked in there (the library) one day and the security guard says, ‘You remind me of somebody.’ He says yeah, with that hat and cowboy boots. He says, ‘When I was a little boy, I’d be on my way to the store to buy some candies with a couple of pennies and pass by these black farmers sitting under this overhang at this potato house – and they’d just be sitting there. They had wide brimmed fedoras and spit-shine boots and khaki and starched shirts. They were farmers but Saturday mornings were their clean up and dress up days…. They’d be sitting there sipping on some moonshine.’ So he told me this story and I said, ‘Man.’

So I just started with a line thinking about this little boy. But then I said, ‘I’m going to make him me.’ So I made the little boy me and told his story. And I think it turned out to be a pretty cool poem. Words just came up out of nowhere. Had I not met this man, had he not approached me, I would have never written this poem. So that poem was there. It was there to be written. It could have been written at some other place, in some other time. But I feel almost pretty certain that that poem was there and it found me.

“Artifacts” was written the same way; it’s a long poem. If you walk over there, you see on the walls of that space -- and it’s an old Kress department store, by the way. You see on the walls they have photographs of old library life – fifties. There are no black people in any of these photographs.

The day I walked in – it’s really kind of like a place where the homeless folks lounge around – it gives them a place to go, you know, during the day? And this is why the security guard is there the whole day long. The day I went there were a lot of homeless people there and on the computers. And everyone on the computers were black people.

But when you look at the library – the old photographs framed and blown up, there’s no black people in them. They have the little white boys and white teachers. I started out just focusing on this one photograph and I just got locked in on it. Then it just blew up. That store was the first store where sit-ins were held in Baton Rouge during the days of civil rights. I think there were Southern students who went there and did sit-ins. So I thought, okay. There is really something here. It’s one of those poems that I think it was there to be written.

It went in a direction that I couldn’t have planned. I just had to let it go and flow. It got to the point when it got past page one, I was like ‘Wait a minute.’ It’s titled “Artifacts” and it’s really about those artifacts of the Jim Crow era, and I brought in a picture of Richard Wright’s – his Dear Madam note: ‘Please let this n***** boy check out some books.’ I brought that into it.

I’ll show you … a photo of my kindergarten class in 1958. The entire class sitting there. Poor black kids being taught by a preacher and his wife, you know. I brought in the Little Rock Nine -- that iconic image of them that day they had to be escorted, and brought Ruby Bridges in there: the army of one.

And then it took a turn that I never planned. I never would have thought, I said, ‘Suppose…what would I tell my grandchildren…Little Devyn…if I brought him to this library, to this space, what would I say to him?’ That to me, is where the poem was really born – at that point.

But again, it’s what I learned from all that, something that Tracy K. Smith taught me. She taught me in a way that was kind of different from what I expected. You don’t sit down and say that I’m gonna write a poem, complete a poem about this. There has to be that moment of spontaneity – when it flies, takes wings. It surprises you. When I get surprised, that’s when I know, ah, that’s poetry, you know?

Tracy made me – every poem that she workshopped, she critiqued it so meticulously and so quickly. She’d sit there reading it and make her little notes. She said, you should think about this, think about that. And I’d ask, ‘How do you know that’s going to work?’ But she doesn’t. She’s just challenging you to open up and be opened up – and let the poem go. Let the poem fly.

The first time she really did that, I was writing this poem – one of my favorites, called “Crossing” at Callaloo. It’s about my father. The first year at Callaloo, 2005, when I got back from the workshop, I discovered that my dad was in the early stages of dementia. By 2007, I was in the thralls of it. So I wrote this poem called “Crossing.”

The last word of it – I don’t know what I had written. But she said, ‘Think of something more delicate.’ I was comparing his mind. So she said, ‘Think of something breakable – that is delicate.’ So I thought of that and then the word ‘crystal’ popped up. And I said, ‘Wow! That’s it!’ But she didn’t tell me to write crystal.

So I began to approach poetry that way – thinking of it as though it were just ‘melting,’ as Robert Frost would say. Let it melt. Let it take its own course. Be open to it and hope that it does. There’s this expectation that something really new and fresh is going to come out of it and that it’s going to surprise me. That’s when I know it’s a poem; when I get surprised.

It’s just like, the “White Lightning” poem. I thought, ‘If I were that boy, what would I hear those farmer’s say? What would they be talking about?’ And at the end, one of them pulls a bottle of White Lightning out of his boot. And without anybody saying – speaking to him – he knew that was his signal to move on. So that’s what I think.

Q. Do you find that your work directing Education’s Next Horizon informs your poetics? Why or why not?

None. Ah, well. In a couple of instances, I can say it has, indirectly. For example, there’s this one poem I wrote called “Bucket.” “Bucket.” I start the poem off talking about those moments where I’m the only black man in the room and we’re talking about the education of black children. I think of this.

With ENH, it’s been work about improving education outcomes for essentially economically disadvantaged children in Louisiana who’ve historically been disadvantaged and all the challenges associated with that that our state has been grappling with for years. So I connect with it more -- I think very passionately -- because that’s me. I was that child, you know? I was that child. I still am that child in a way. I was able to provide my own children and grandchildren with a better path.

What strikes me is that here we are in 2020 still dealing with these issues. And it sort of keeps me in that space. I never get bored with the work. I have the passion and very intimate relationship with the issues. But it doesn’t inspire a whole lot of poetry.

My first big job in corporate America, my supervisor used the N-word and it started off with a reflection on black children but it ended up being a reflection on how oftentimes we find ourselves as black men in a room and when we should be speaking out, we aren’t. We’re sitting there with our mouths shut. It’s almost like stooping low. It’s almost like Booker T. Washington’s – “cast down your bucket.”

When we need to get things from white people, without even knowing it, we become complicit. We go with it. We don’t challenge it. Because there’s something there we want. There’s something we need.

Learn more about John Warner Smith from his website. The poems below have been included with the generous permission of the author.

Bucket

Sometimes, when I’m the only black man in the room,

sitting under the soft, quiet glow of enlightenment,

talking about building an education system

to save mostly black children,

I feel what I felt one day in ninth grade

when I stood in a lunch line

and a slimy blob of spit hit the back of my neck

like a large, stinging rock,

and I turned around

to find a sea of white faces sneering back.

I feel what I felt years later

when a corporate recruiter said,

You’re the type we’d like to groom,

and I stepped out of the city’s tallest building,

wearing my blue pinstripe polyester suit,

carrying my vinyl attaché case, looking back

at a glass tower with carpet so plush

I’d kick my shoes off and think

I had arrived, until the day

my supervisor used the “n” word

when he saw a white cop beating

an old black man on a downtown street,

and I remembered a joke he told

weeks before: that when cops in Beaumont

arrested a drunk, vagrant black man

in the middle of the night

they sobered him up

by driving him ten miles

and dropping him off

at a curbside in Vidor,

where everybody was the Klan.

I feel what I felt and what my daddy

and every black man before us felt

at some time in our lives,

when a white man had something we needed

and we couldn’t get it

without stooping low, bending over

and casting down a bucket,

or just keeping our mouths shut.

Crossing

I

Workdays you tiptoed the high wire

and steep cliff ledge, wearing blue twill

and a bright orange vest,

each crosswalk a sea, a compass, a cargo of children.

Still, Earth passed you by

with time pieces you strapped

to each wrist for trips to Texas and California,

circling city blocks and returning home.

“Something has fallen out of my head,”

you said, just weeks before

Katrina made bones of the city

and broke the hand of Jesus.

When Rita came exhaling,

I begged you to leave,

but you stayed— half-beast, half-child,

living in no-man’s-land,

You resisted my tearing down

the great wall you built of ants,

souring pots and junk mail.

One morning I pulled a drawer

and found your pistol, old vials of blue pills

and years of unspent cash.

II

Stars drown

in the black drone of waves.

You cross

in cold light.

You lie down

with newborn fields

and scented voices,

a titter and a word

short of laughter.

Hands lock in a mudra.

We feed you.

Old vessel, sweet daemon,

do we cage you crib-like

to protect you from yourself?

Or is it the delicate crystal within

we fear?

Stars

New Orleans, a Tuesday, 7:30 A.M.

I’m sipping coffee at a McDonald’s on Canal

when two young black men, early twenties perhaps,

walk in, buying nothing. Suddenly,

I’m aboard a mother ship,

streaking toward the farthest stars.

One, like a fly, bobs the aisles, sweaty

in his Crown Royal muscle shirt.

Gym shorts hanging off his ass,

headset in his ears, he pantomimes

a singer and dances a Mardi Gras mambo

in July, with himself, second lining

silky-smoothly across the floor, out the door,

onto the parking lot—his own block party

without the block.

The other, well-groomed, small backpack,

talks loudly, eloquently to himself

about home, what it is, isn’t and should be, then,

facing the faces, he launches a soliloquy

of senseless babble,

and you sense the other--

the voices, a stage, curtain and cast,

his fans and followers looking on,

inside his head.

I’m gazing stars. Drawn to the glow

of their wayward worlds,

I can’t help

but pause, watch and listen.

I’m entertained,

but scared, because they’re black men

and I’m one, too,

with a son and grandsons of my own,

and I can’t help

but ponder: what’s loose,

what’s broken, what’s gone wrong,

what’s the fix?

Help support our creative team –become a member of our Readers’ Circle now!