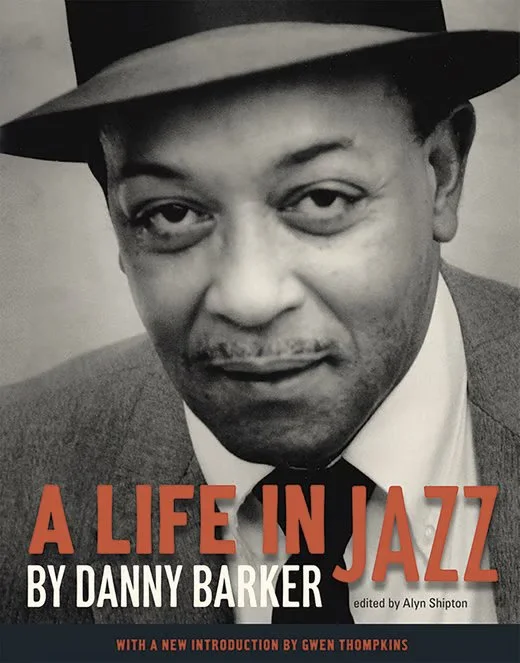

Danny Barker and the New Orleans Axeman: A Jazz Parable

December 2025A noted Creole jazz musician, raised in the French Quarter’s Little Palermo, embarks on a mission to preserve the soundtrack of New Orleans’ culture.

– by Bethany Ewald Bultman

This column is underwritten in part by Lucy Burnett

“On St. Joseph’s night, March 19, 1919, a local axe murderer vowed to spare anyone who had a jazz band playing in their homes!”

New Orleans’ jazz guru, Danny Moses Barker, spun out the story dramatically and continued with a flourish. “Jazz saved New Orleans that night!” he would say.

By 1969, Barker had discovered that the grisly murder story was an effective way to convert quasi-intoxicated Bourbon Street tourists into paying customers at the New Orleans Jazz Museum (NOJM).

The decade-old French Quarter museum had recently moved into its second location at the swank new Royal Sonesta Hotel on the 300 block of Bourbon. Barker held down the fort of traditional jazz as the museum’s assistant curator from 1969 to 1971.

To Danny Barker, this role carried a level of responsibility akin to that of a brain surgeon. In order to entice disengaged visitors to pay jazz its due at the world’s first jazz museum, he had to “make show.” At those times, he’d employ his mantra for embellished storytelling: “If it wasn’t exactly true, it surely ought to be.”

But while his opening gambit to museum visitors was usually less terrifying, it was equally as fascinating.

“I was just ten years old when I played my first professional gig,” I often heard him say.

At the time, I was a nineteen-year-old native of Natchez, Mississippi, a Tulane junior working part-time at the French Quarter’s plucky newspaper, TheVieux Carre Courier. The chair of the Tulane History Department, Dr. William Ranson Hogan, was one of my esteemed professors. In 1958, Dr. Hogan had secured a Ford Foundation grant to help Tulane become the first university in the world to create a jazz archive.

He taught that jazz was a vital voice of social change. In 1969, Danny Barker was the guest scholar whom Dr. Hogan invited to explain why.

Danny captivated my fellow students and me by combining the cadence of African folktales with the gravitas of Bible parables. His stories of cultural history were played out on a stage populated by tricksters and villains who committed wrongs and rights in equal measure.

“Next time you walk by one of those lifesized Black mammy statues outside the praline shops in the Quarter,” he told us as he waved his cigarette like a conductor’s baton, “lean over and ask her, ‘what kind of music do you listen to when you get home, sugah?’ And I bet she will tell you, jazz, baby!”

***

“There are latrine smells and disinfectant smells and booze smells and people smells and horse smells along with kitchen odors, as if everything and the body of Bourbon street were being cooked in one grotesque bouillabaisse.”

Art Seidenbaum , “Fleshy French Quarter-Treat or Trap,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 18, 1973

Several afternoons a week, I plotted my route back uptown from the Courier’s Decatur street office to the St. Charles streetcar stop so I could drop by to soak up Danny’s encyclopedic ethno-cultural knowledge.

The small museum had moved into the Sonesta in 1969 at the invitation of the hotel’s visionary developer/manager, James Achilles Nassikas. Nassikas also served as President of the New Orleans Jazz Club and the NOJM. He and the Sonesta had become important allies in the long-time efforts of Louis Cottrel, Jr., who had been working for decades to attain union-scale pay for Black musicians playing at Bourbon Street clubs.

There was only one problem. The 241-room Sonesta, which opened in July 1966 on the site of an old local brewery, became synonymous with the struggles of traditional jazz on Bourbon Street.

Bourbon Street had fallen on hard times. The local police had unintentionally transformed the Sonesta into a counterculture shrine on January 31, 1970 with the infamous Grateful Dead bust. Within a few days, leather-clad bikers, allegedly leftover extras from Easy Rider, loitered outside on the sidewalks slick from discarded, buttered corn cobs and “go-cups.”

As they awaited another bust, or the arrival of a visiting rock band, they mingled with chanting Hare Krishnas and tie-dyed flower children holding tongue-in-cheek "Rent a Hippie" signs. With air permeated with the aromas of patchouli, pot, and the cloying fumes of Boone’s Farm Apple Wine, venturing into the New Orleans Jazz Museum took resolve.

Aside from the British and Japanese music aficionados, who had made pilgrimages to the city where jazz was born, few French Quarter tourists had the patience to unlock the treasures of the museum Barker offered. Fewer still grasped the fact that they were in the presence of a true American cultural icon.

***

“Jazz was a syncopated musical response that thumbed its nose, complained about the misery and jumped for joy about survival- all the while getting feet stamping. African call and response; gospel; folk tunes and juiced up pompous military bands rifting in and out. There was no containing the audacity and flamboyance.”

The Good Times Rolled: Black New Orleans, 1979-1982, Bernard Hermann, Publishers: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2015.

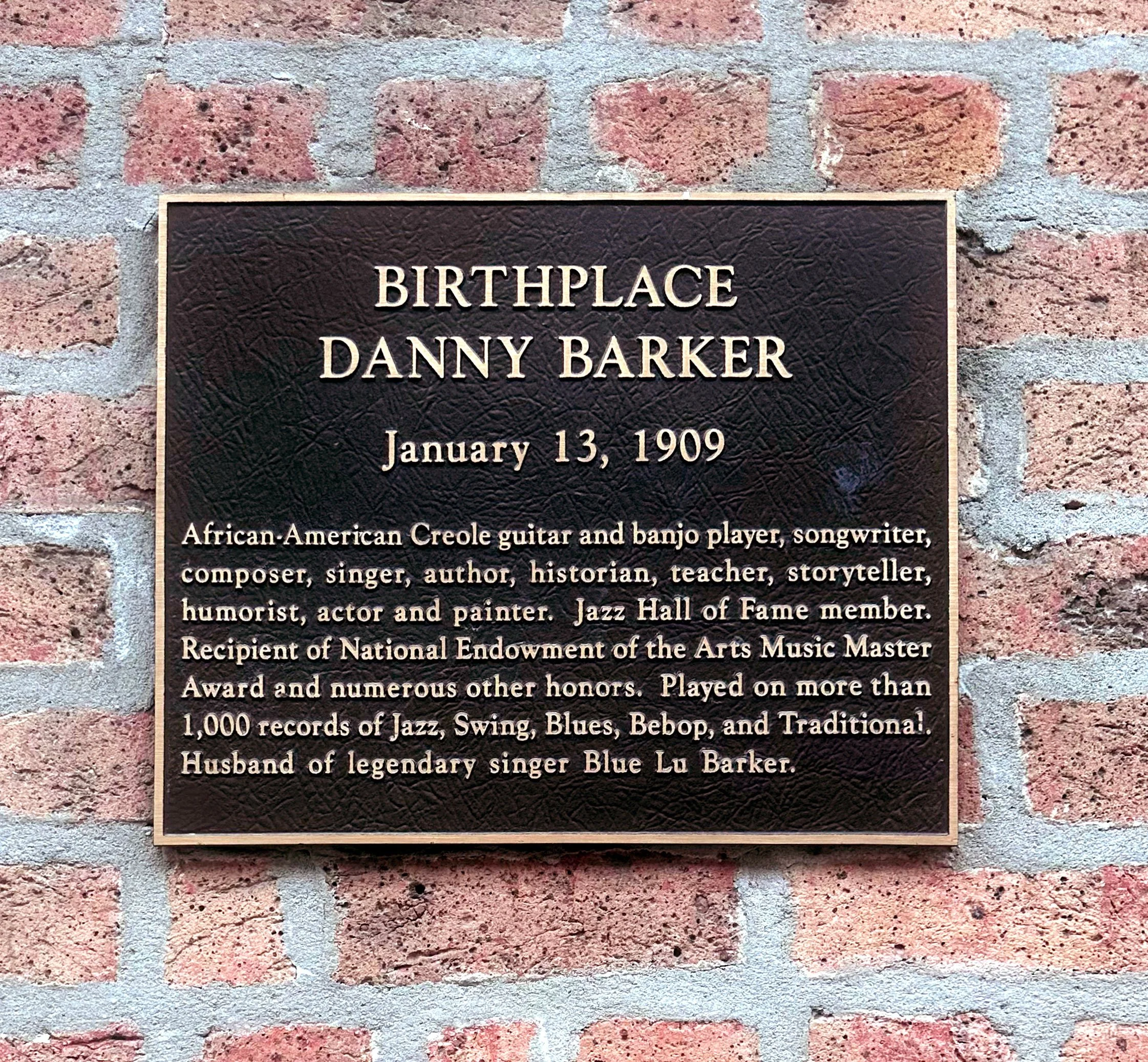

Daniel Moses “Danny” Barker was born on January 13, 1909, in the heart of the French Quarter, the tight-knit Sicilian section known as “Little Palermo.” His father, Moses, was a “hollerin’ and jumpin’ hard-shell Baptist,” and his mother, Rose, was a devout Creole Catholic, steeped in ritual.

Adolphe Paul Barbarin (1899-1969), only ten years older, was his uncle. His Uncle Paul also served as Danny’s godfather and musical mentor. He introduced him to percussion when Danny was “knee high to a grasshopper.” Soon, the boy moved on to learn the clarinet before settling on strings: ukulele, guitar, and banjo.

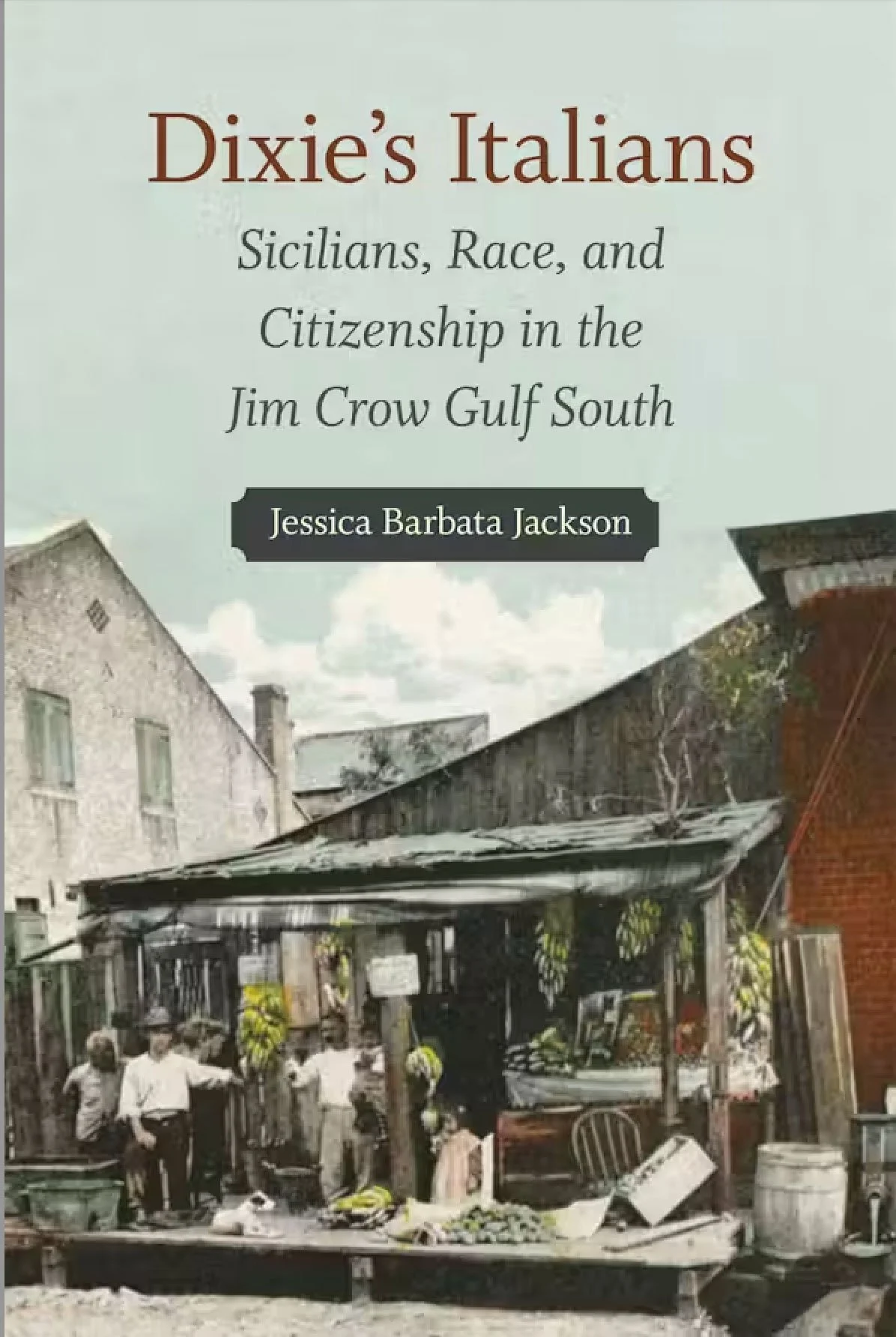

Within months, the child prodigy identified as a working musician. Danny Barker and his Sicilian pals picked up a few pennies (and unsold produce to help feed their families) by playing music on the back of vegetable carts or in front of fruit stands to lure customers.

In 1969, when Danny and I talked away the afternoons when no tourists happened into the museum, he would click off the various forms of music that percolated from his boyhood spent a block from St. Mary’s Italian Church, where, on saints’ days, Chartres Street was filled with brightly attired, prancing and swaying Sicilian folk. Dancers twirled parasols to the lilting triple meter folk music evolved from centuries of ancient melodies of Greece, Byzantine, and Spain.

By tapping on the museum’s empty cash box with two metal-capped fountain pens, Danny taught me the distinctive local beats from long ago. One of his favorite rhythms came from the “cupa cupa,” a unique friction drum his uncle Paul Barbarin taught him to play.

Danny often referred to his “Uncle Paulino Barbarino,” who introduced him to Sicilian-speaking, classically-trained musician neighbors. Many played for the opera and ballet companies with some of their Barbarin kinfolks – in violation of Louisiana’s complex racial dictates.

The young Danny Barker observed how Jim Crowe’s cousin – “Giacomo” Crow – vilified these immigrant neighbors, making them “in-between people.” The Sicilians had neither white privilege or status that could be found as part of the Barbarin’s Creole music aristocracy. And he lived near the place where eleven Sicilian men were lynched in 1890.

Nearly thirty years after the horrific lynchings, the prejudice and discrimination that Sicilians still endured in New Orleans – and nationally – created an environment that spawned a mass murderer when Danny was a young boy, one who came to be known as the Axeman.

“It was America’s own Bayou Jack the Ripper,” explains Miriam Davis, PhD. in her book, The Axeman of New Orleans: The True Story.

In the early 1900s, half of all New Orleans’ groceries were owned by Sicilian immigrants. Between May 1918 – October 1919, twelve Sicilian grocers and their families were assaulted. Five died of their wounds.

In her book, Davis writes that “his modus operandi, a borrowed ax from his own victims, he bludgeoned them while helpless and sleeping soundly in their beds.”

The hysteria surrounding the Axman bridged all New Orleans’ social classes, as newsboys hollered out details of each grisly attack. Nine-year-old Danny was terrified that someone he knew would become a victim. When this real-life Hannibal Lecter’s murderous rampage stopped, it proved to the boy that jazz could be a significant community unifier.

***

"Playing this music is like taking a ride on a royal camel. That's a great ride, to be riding on a royal camel with the kings and queens. That's what it's like when you learn this music."- Danny Barker to Greg Stafford, NPR interview with Gwen Tompkins (December 10, 2016)

In 1919, Danny’s uncle Paul Barbarin joined the exodus of New Orleans jazz greats to Chicago. By the mid-1920s, Danny, too, was touring the Deep South with Little Brother Montgomery. Eventually, he moved into a Harlem apartment with his Uncle Paul.

From 1939-46, Barker became the dazzling guitarist anchoring the rhythm section of Cabell “Cab’ Calloway’s big band. Calloway was the first African-American musician to sell a million copies of a record and to host a nationally syndicated radio show.

Danny Barker became a bona fide “made good” in New Orleans after he was featured with Cab Calloway’s band in the 1943 film, Stormy Weather.

Then in 1965, Danny returned home to the birthplace of jazz. He, like his namesake, Moses, was on a mission. The fact that jazz saved New Orleans in 1919 was the glimmer of hope as he kept watch over hundreds of NOJM’s precious jazz artifacts.

Time was not on Dixieland jazz’s side, though. Danny and his fellow jazz immortals were aging. The airwaves were dominated by rock' n' roll. To get their money’s worth at the NOJM, some of the visitors from the drugs/sex/rock generation insisted that Danny spill the tea on Elvis’ time in New Orleans or the Beatles’ local concerts.

Danny didn’t budge. He would nonchalantly hum “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It” as he’d polish a cherished museum artifact with a red banana.

I’d often witness the disappointed tourists heading out of the museum toward the hustle of Bourbon Street. Danny would fix them with one of his imperious deadpan stares, which he’d slowly rotate heavenward. Once they’d disappeared, he’d belt out a verse from a ‘Closer Walk with Thee”:

“Through this world of toils and snares, If I falter, Lord, who cares? None but Thee, dear Lord, none but Thee.”

After keeping a daily vigil over jazz’s treasures, Danny’s single-minded dedication to the art form’s legacy inspired him to recruit a new generation of jazz men to keep its power alive. In collaboration with the Reverend Andrew Darby, Jr, he founded The Fairview Baptist Christian Marching Band (1970-74), his chosen young disciples to spread the message.