Artist Glenn E. Miller: Looking Closer

Glenn Miller in Jackson Square, November 2025 by Ellis Anderson

December 2025An aspiring artist arrives in the mid-60s French Quarter to begin his career in Jackson Square – one that would include several misadventures and six decades of pushing the creative envelope.

– by Michael Warner

This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

The airman thanked the driver for the lift from Keesler Air Force Base to New Orleans. The year was 1966 and medic Glenn E. Miller was 20 years old. When he stepped out of the car in the French Quarter, he was still wearing his uniform. But as soon as he found a private spot, he pulled out his “beatnik clothes” and changed, neatly folding his uniform and storing it away in his pack.

Glenn Miller at 19, the day he met Jayne Mansfield at Keesler Air Force base in Biloxi. Image courtesy Glenn Miller

“I tried to avoid the draft. So I joined the Air Force, and they made me a medic. I was a beatnik type of guy. And so I started fantasizing about New Orleans.”

It was easy for him to get picked up as he thumbed his way along Highway 90 from Biloxi, provided he was in uniform. “You know, it’s like, free rides,” he said. And that’s when he fell in love with the Crescent City. Every weekend, he made the trek.

Since he was an Air Force medic, Glenn worked at Keesler Hospital. On June 28, 1967, he was assigned an unusual task: he was to guide actress Jayne Mansfield on a tour to visit soldiers wounded in Vietnam.

“I was a little awestruck and didn’t talk much, but I answered her questions and introduced her to each guy,” he said. “She had on a flowing, low-cut white dress, and her hair was in a bouffant, the style of the day. She smelled good; I think it was an expensive perfume. I remember her voice was like a little girl’s.”

That evening, Mansfield gave the last performance of her career at Gus Stevens Restaurant and Buccaneer Bar in Biloxi. Hours later, on the road to New Orleans, Mansfield died in a horrific auto accident that also took the driver and her lawyer. Mansfield’s three children, asleep in the back seat, survived.

Glenn was saddened by the immediacy of this tragedy. But, he still remembers the evening with her. “I was living a dream, she was like an apparition from heaven.”

The Louisiana city he loved offered a different kind of allure: New Orleans was on the verge of a counterculture golden age in politics and in the arts and literature. Darlene Fife and Bob Head had founded NOLA Express, a cornerstone of the underground newspaper movement. The city was a stopping point for many young people running the circuit from San Francisco to New York – roughly along a trail blazed by the likes of author Jack Kerouac in On the Road and beat poet William Burroughs in the 1940s.

Protests against the Vietnam War were gaining ground. Experiments in free speech were freaking out officials. The artist community around Jackson Square was growing explosively and the city would soon propose a license system to regulate the display of artwork on the iron fence.

And one of the cheapest places to live was the French Quarter.

After being discharged from the Air Force, Glenn returned to his hometown of Meadville, Pennsylvania, where he lived with his parents for a while. After a failed engagement, “everything went to crap,” he said. So in 1968, he and childhood friend Jack Miller (no relation) caravanned their way down to New Orleans – Glenn in his old Morris Minor pickup and Jack in his MG.

Both Millers set up on Jackson Square to sell their art to tourists and to scratch out a living. He had been producing artwork while in the military – charcoal drawings and watercolors – but not the etchings for which he later became known.

“A lot of these guys were really well-trained artists,” said Glenn. “They had good educations, they went to prominent schools and they were being shown in good galleries.” He felt overwhelmed by his new colleagues' skills, but he kept pushing and learning.

To supplement his income, Glenn sold newspapers – and not just any old establishment newspaper. He sold the NOLA Express, buying the sheets from the publisher at half price and hawking them on the street corner.

“You made your money back – you doubled your money on everything you sold,” he said.

As he became friends with publisher Bob Head, NOLA Express began to feature Glenn’s illustrations, which he characterized as “wild, out there, you know, crazy stuff.” Rather than cash, Head paid him in newspapers, which Glenn would sell. Soon The Word, another New Orleans underground paper, also ran Glenn’s illustrations.

Glenn remembered Head as a true French Quarter character. “He lived real simple like a monk, you know. But he had a shotgun there by his door because he was paranoid.”

According to Glenn, Head was under constant surveillance by the police and local officials because NOLA Express highlighted articles about political corruption and the Vietnam War. Head installed a series of door locks, and he screened visitors before allowing them into his office. He’d received regular threats, said Glenn, though the threats did not impede his reporting.

It being the 1960s and the era of free love, Glenn and Jack became interested in erotic art, a genre that they produced in abundance. After stockpiling a significant supply of drawings and sculptures, the two decided to put on a show.

“It’s art, you know,” Glenn said. “People need to open their minds. That’s the kind of philosophy we had.”

The two procured use of the old Methodist church at 601 Esplanade Avenue at Chartres Street, which their friend Bob Moyer had been using for improvisational theater. The exhibition was as much performance art as it was sculpture and drawings. The two found an old toilet bowl, which they scrubbed and filled with yellow punch, much to the amusement of thirsty attendees.

They talked a woman into undressing and lay her down on a banquet table, covering her with a wet sheet. From atop her body, they served a buffet and hors d’oeuvres.

Glenn hung a 10-foot papier-mache phallus from the ceiling.

“We were wild,” said Glenn. “I mean, we were very radical people. So everything was going good. The show was a big success. People are coming, they couldn’t believe it, and they’re having fun.”

Then they ran out of wine.

According to Glenn, someone gave him a few bucks and told him to run down to the wine shop for supplies. It took a while. Glenn was on foot and the wine store was blocks away. Forty-five minutes or more later, he returned, lugging a box of bottles and discovered the door of the church had been padlocked. The police had raided the place.

“Jack got arrested,” said Glenn. “Bob Moyer got arrested. Imagine, he’s a Tulane graduate student. Married, had a kid, and he’s hauled off for – they called it pornography.”

Glenn Miller, Mardi Gras 2022, photo by Ellis Anderson

At that time, police and prosecutors in New Orleans commonly used pornography charges to arrest dissidents and sellers of underground publications.

To avoid arrest, Glenn relocated to Kenner, where Jack Miller had a place. But after months of court hearings, with the ACLU's help, the defendants were victorious. Glenn never did recover the confiscated artwork. He thinks it was destroyed.

Glenn retained his interest in free speech, though. One day, he stopped in at the Seven Seas Bar on St. Philip Street, where he hit it off with a fellow named John Bennett. As publisher of The Word underground newspaper, Bennett was about to embark on a prolific writing career. A few years earlier, at the start of what some call the “Mimeo Revolution,” Bennett had founded Vagabond Press, a venue for works by such writers as Charles Bukowski and T.L. Kryss.

Weeks after meeting Bennett, Glenn was strolling in front of the old Dixie Bank (now the French Quarter Police Station at 334 Royal), which was undergoing renovations. On the street, atop a pile of construction debris, rested a 1917 A.B. Dick mimeograph machine crafted of ornate brass and polished wood. Immediately enamored, Glenn brought it home and restored it to working order.

“I went to Bennett and said, look, I found this mimeograph machine. Let’s start printing some chapbooks.” And for the next several years, Bennett used that device to publish Vagabond Magazine. He made Glenn art editor. The machine now resides in the Washington State University Library collection.

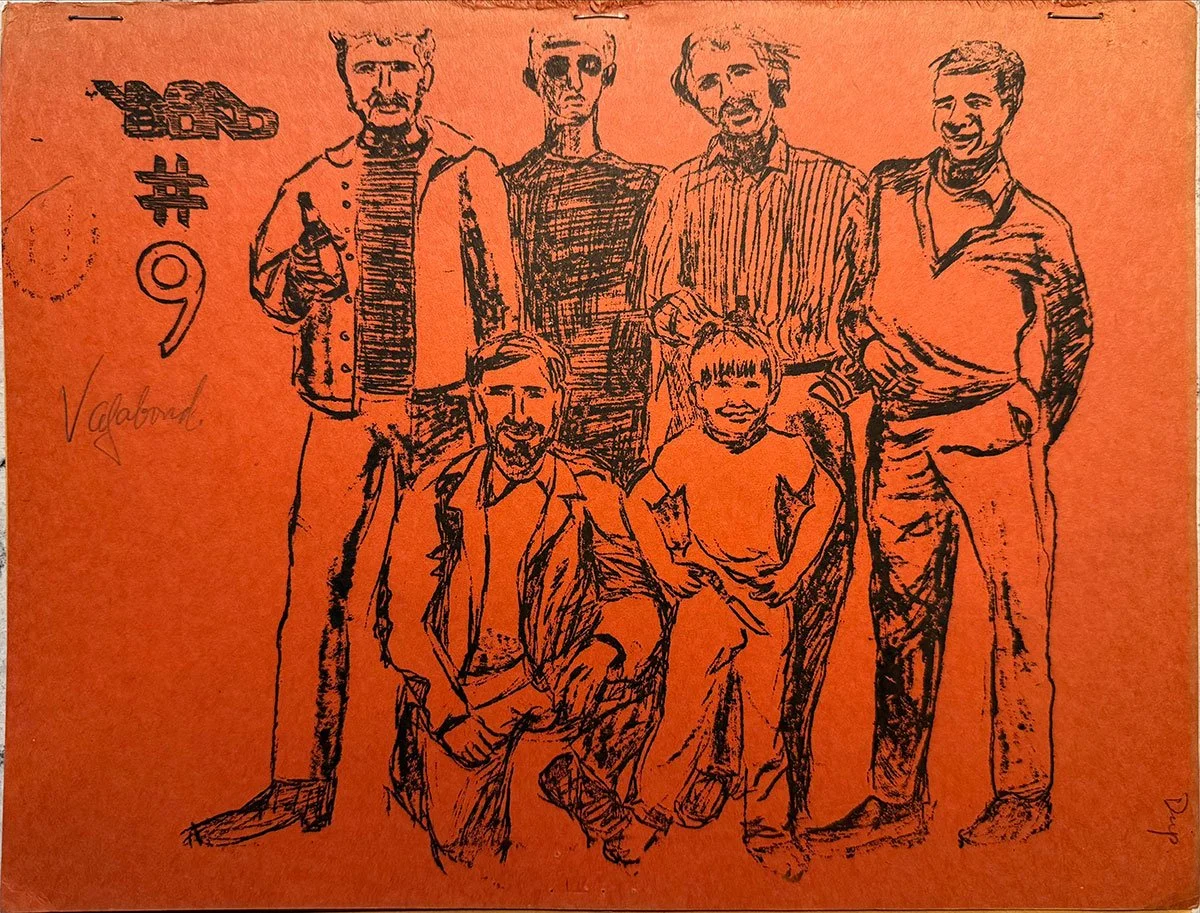

Cover of Vagabond Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 9 (San Francisco, 1969), drawn by Glenn E. Miller. John Bennett is front row, kneeling on the left. His young son stands next to him. The volume was printed in San Francisco on rough construction paper using the mimeograph machine found by Miller on a trash heap on Royal Street in 1968 or 1969.

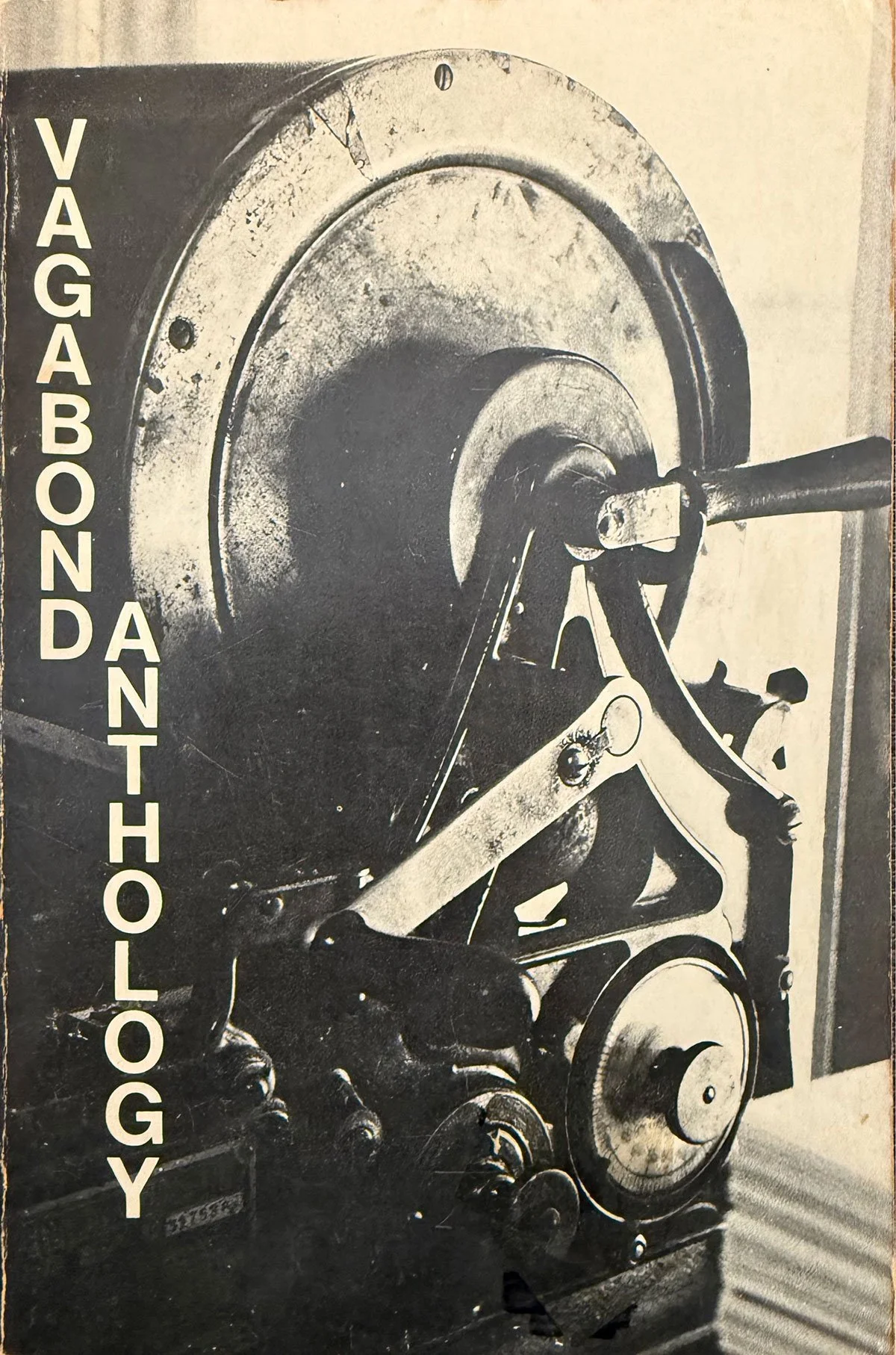

Cover of Vagabond Anthology, 1966-1977 (Vagabond Press, 1978), edited by John Bennett. The book reproduces many of the best stories and poetry published by Vagabond Magazine during its 11-year run. This cover photo shows the mimeograph machine Miller found in a trash heap on Royal Street.

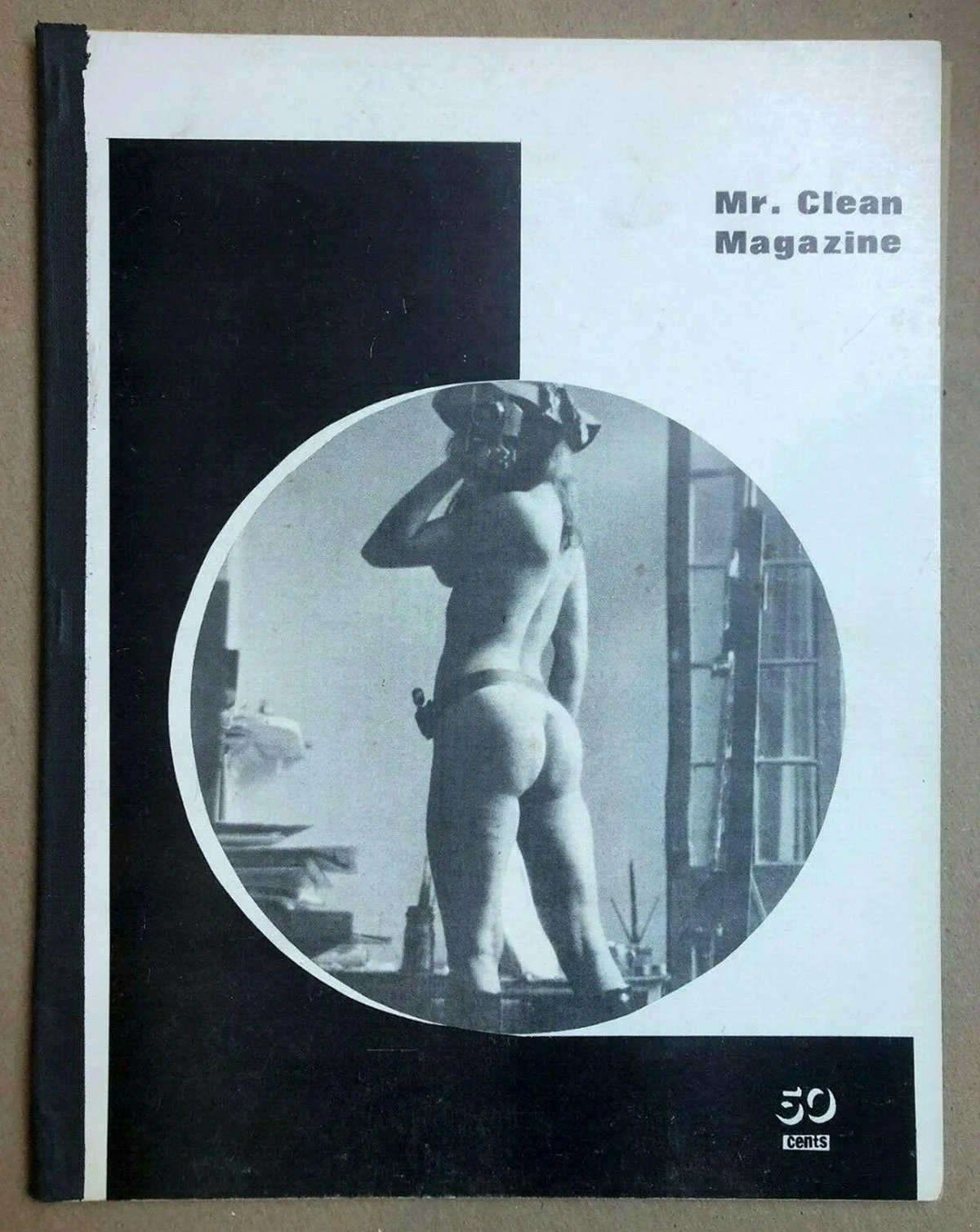

According to a 2002 interview of Bennett, one of their publications was called Mr. Clean Magazine. Glenn said the cover featured a standing nude woman, shown from the back – a self-portrait of Nancy Davis, a free-lance photographer.

“Landed me and Glenn Miller . . . in jail on pornography charges,” Bennett said. “I got the hell out of New Orleans after that.” He moved to the Mission District of San Francisco.

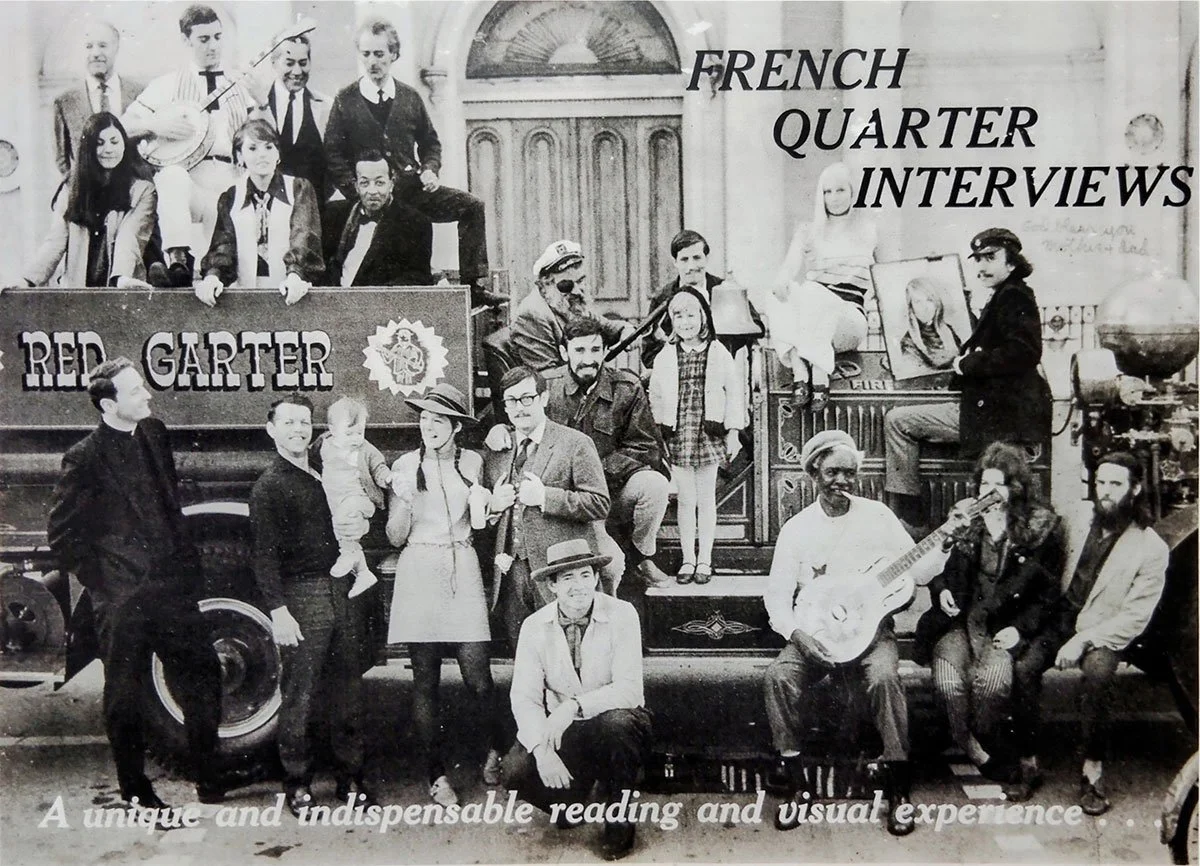

Advertisement poster for John Bennett’s book, French Quarter Interviews (Vagabond Press, New Orleans, 1969). Glenn E. Miller is top right, in the fisherman’s cap and CPO jacket, displaying a portrait of the woman sitting atop the fire truck hood. John Bennett is the dark-bearded man in the center of the photo looking into the camera. Marty Rudolph sits on the fender of the truck, far right. The man sitting on the fire truck’s fender, holding the guitar, is Blues great Babe Stovall (1907-1974). In the group sitting in the bed of the fire truck (top left), front row on right, is Jazz great Danny Barker (1909-1974). (Photo by Nancy Davis)

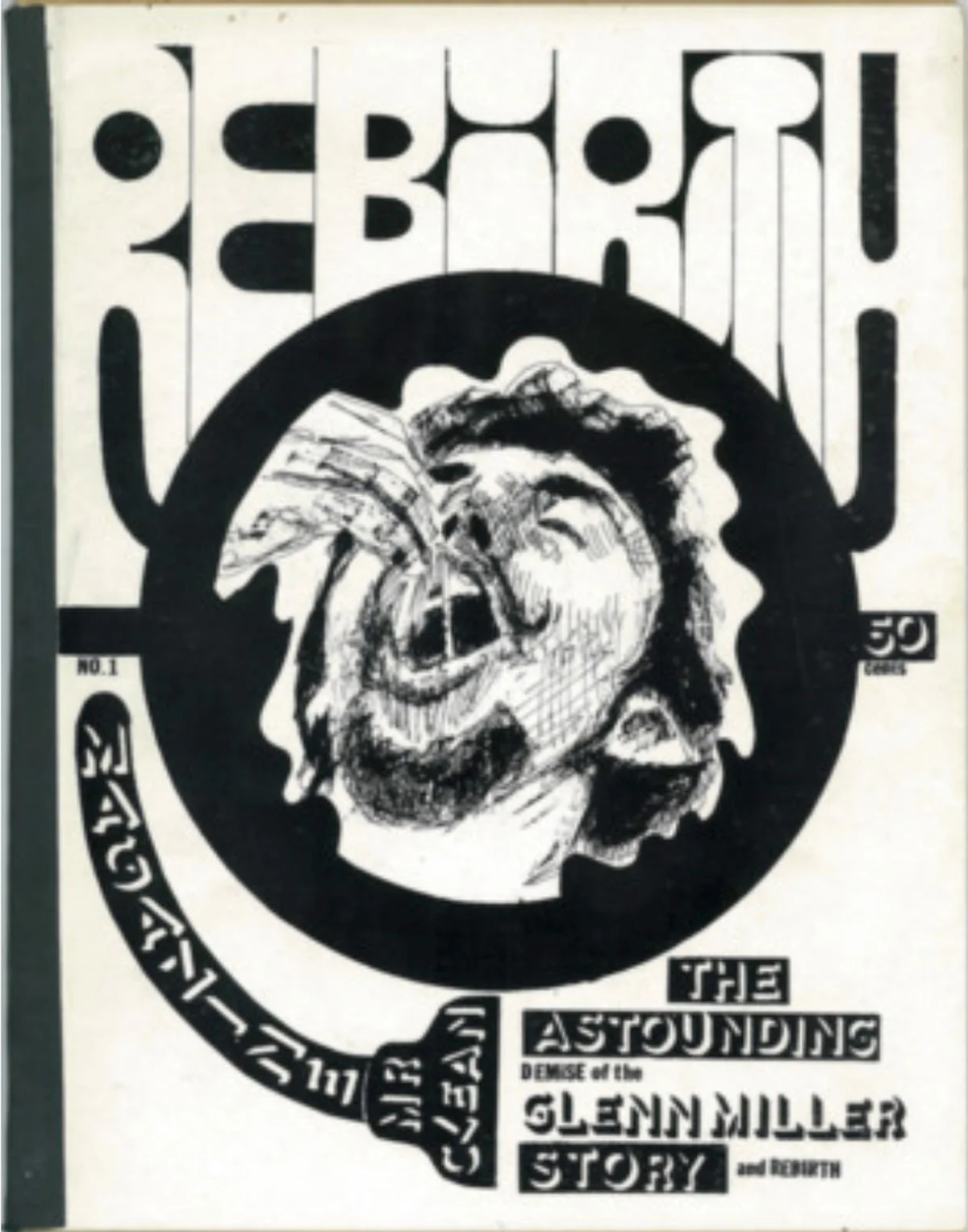

Cover of Mr. Clean Magazine, No. 1 (New Orleans, 1969). (Self-portrait cover art by Glenn E. Miller)

Cover of Mr. Clean Magazine, No. 2 (New Orleans, 1969), featuring a cover photo by Nancy Davis. This cover was cited in the arrest of art editor Glenn E. Miller and publisher John Bennett on pornography charges in 1969.

Simply selling underground publications in 1969 did not provide Glenn with the means to live. “I was selling pot, too. . . . I say I invented pot for white people.”

To procure his supply of marijuana, Glenn said he and friend Marty Rudolph attended jazz clubs in surrounding neighborhoods and bought marijuana. With his stash tucked out of sight in his underwear, Glenn would return to the French Quarter and stand on the street, scanning passersby for potential customers. To a select few, he would whisper as they passed: “You want some pot?”

But according to newspaper accounts, on February 15, 1969, Rudolph was arrested for alleged possession and sales of narcotics as part of a wide drug sweep through the French Quarter. It was a while before Glenn heard of the bust.

“I walk into the Seven Seas [bar], and they’re like, ‘Glenn, what are you doing here, man? The cops were just in here looking for you.’ ” He quickly packed a rucksack and headed out of town, and soon he was thumbing his way to San Francisco to stay with Bennett.

Sign in front of the Seven Seas Bar on St. Philip Street, a frequent hangout of Miller and other members of the New Orleans art and literature communities in the late 1960s and early 1970s. (Wikimedia Commons)

Now basically homeless in San Francisco and unable to find a job, Glenn shifted between apartments of friends in Bennett’s circle. One such friend was Lawrence Ferlinghetti, beat poet and co-owner of City Lights Bookstore. Glenn crashed for several nights in the shop’s back room.

“He’d let you sleep in the back room if he liked you. [Bennett] recommended me, you know, to sleep in the City Lights.”

Italian espresso shops in the North Beach neighborhood became a hangout for Glenn and the rest of San Francisco’s aging beatnik community, by this time giving way to a new generation of hippies.

“You’d see old beatniks and they're all getting gray and still sitting around and reading their books and playing chess,” he recalled.

Glenn often came across counterculture cartoonist R. Crumb in these coffee shops and would literally study over the artist’s shoulder. Crumb was already famous for his cover of Janis Joplin’s Cheap Thrills album and for his illustrations in Rolling Stone magazine.

“I can't say I really met him, because he wasn’t all that friendly. He was awkward, not really outgoing. But you know I looked over his shoulder, and I’d watch what he's doing. I picked up a lot of tips from him. I picked up [use of] the Rapidograph pen.” Glenn still uses a Rapidograph.

Ferlinghetti and Bennett introduced Glenn to Charles Bukowski and other beat poets. To get into this group, Glenn said, you had to write a decent poem. And talk poetry. And talk jazz. And philosophy. And you had to understand all the modern authors.

But this group was not composed of particularly warm people, Glenn found. “They were kind of wrapped up in the nihilistic, you know? In their philosophy. You could hardly get a happy poem out of them.”

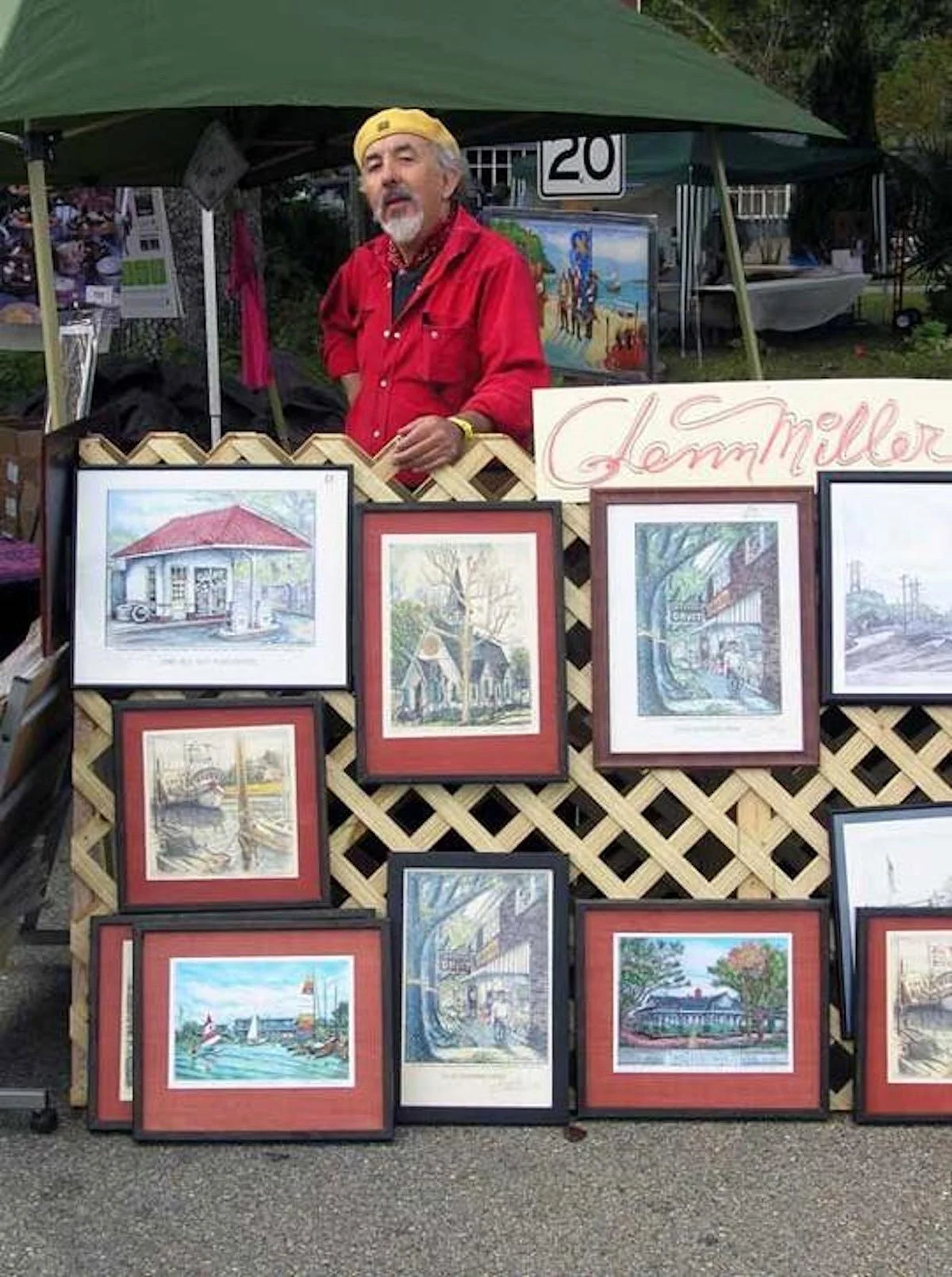

Glenn Miller on Jackson Square, 2019. Photo by Ellis Anderson

Sometimes Bukowski and Bennett would talk, and Glenn would sit on the sidelines. Bennett had an apartment in the Mission District of San Francisco, where one day he invited a young woman and Glenn to sit in the apartment’s ground-level courtyard for beer and conversation with Bukowski. The “apartment” was actually a converted pigeon coop on the roof of the building. Bennett would list his address as “66 Dorland (roof).”

According to Glenn, Bukowski suggested that Bennett and the woman should go up with him to Bennett’s pad—but not Glenn. To Glenn, he said, “You guard the beer.”

“They go, the three of them,” Glenn said. “I ended up, I was stranded. I stayed there all night,” sleeping on the picnic table.

Moving from one crash pad to another, unemployed but for the occasional illustration in an underground paper, constantly drinking, taking reds, and smoking dope, Glenn started a downward spiral.

But he credits his recovery to a group of Christians, a “Jesus Freak commune,” he called them. They got him off drugs, off alcohol, and off the street. Soon, “I got my head straight,” found a job, and realized that those aging beat poets were not good influences.

“And, you know, I mean, it opened up a lot of things for me. And then I came back to New Orleans.”

That was about 1970, not long after the Sharon Tate murder, and drivers were rather less willing to pick up long-haired hitchhiking strangers. But after a few days on the road, Glenn arrived in the French Quarter. He fell in with his old friend Jack Miller, and they began creating linoleum block prints.

Glenn Miller, Artist, photo by Jean Carlisle, 1976. (Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Brother Martin High School, 1992.128.17)

Miller in September, 2025, nearly fifty years after the photo with the etching press was taken. Photo courtesy Glenn E. Miller

Carey Beckham and Alton Cook, founders of Beckham’s Bookshop, saw their work in a show and hired Glenn to manage their print gallery at 829 Royal Street. It was through this gallery that Glenn met Eugene Loving, a long-established New Orleans etcher.

Loving had arrived in New Orleans in 1931 after spending years as a Merchant Mariner between ports in South Africa, the Middle East and Europe. He was not a person to shy away from trouble.

A year or so after arriving in New Orleans, Loving was arrested for his part in a gang of robbers that targeted beer parlors during Prohibition. According to their business model, selling beer at that time was illegal, so the bar owners would be reluctant to report any robberies.

Unfortunately for Loving and his colleagues, New Orleans police did not particularly care about the laws of Prohibition, and the gang was soon arrested. He served his time and had a few more scrapes with the law. But eventually he went straight and began a career as an etcher, creating detailed and realistic images of French Quarter scenes.

In 1971, Glenn talked Loving into taking him on as an apprentice to learn the craft of etching. Through Loving, Glenn met New Orleans artist and former journalist Charles Whitfield Richards during a beer-steeped evening at the bar in Matassa’s Market on Dauphine Street. Then, being a teetotaler, Glenn ordered a steady supply of Barq’s for himself.

With Norm Criner, another regular of the New Orleans etching scene, this group took trips to Criner’s cabin in Covington for long weekends of imbibing, storytelling and print-making.

And Glenn built an artistic career from that print-making experience. He graduated from the University of New Orleans in 1978, majoring in art, and then attended Tulane’s MFA program for a while, where he studied under veteran artist James Steg.

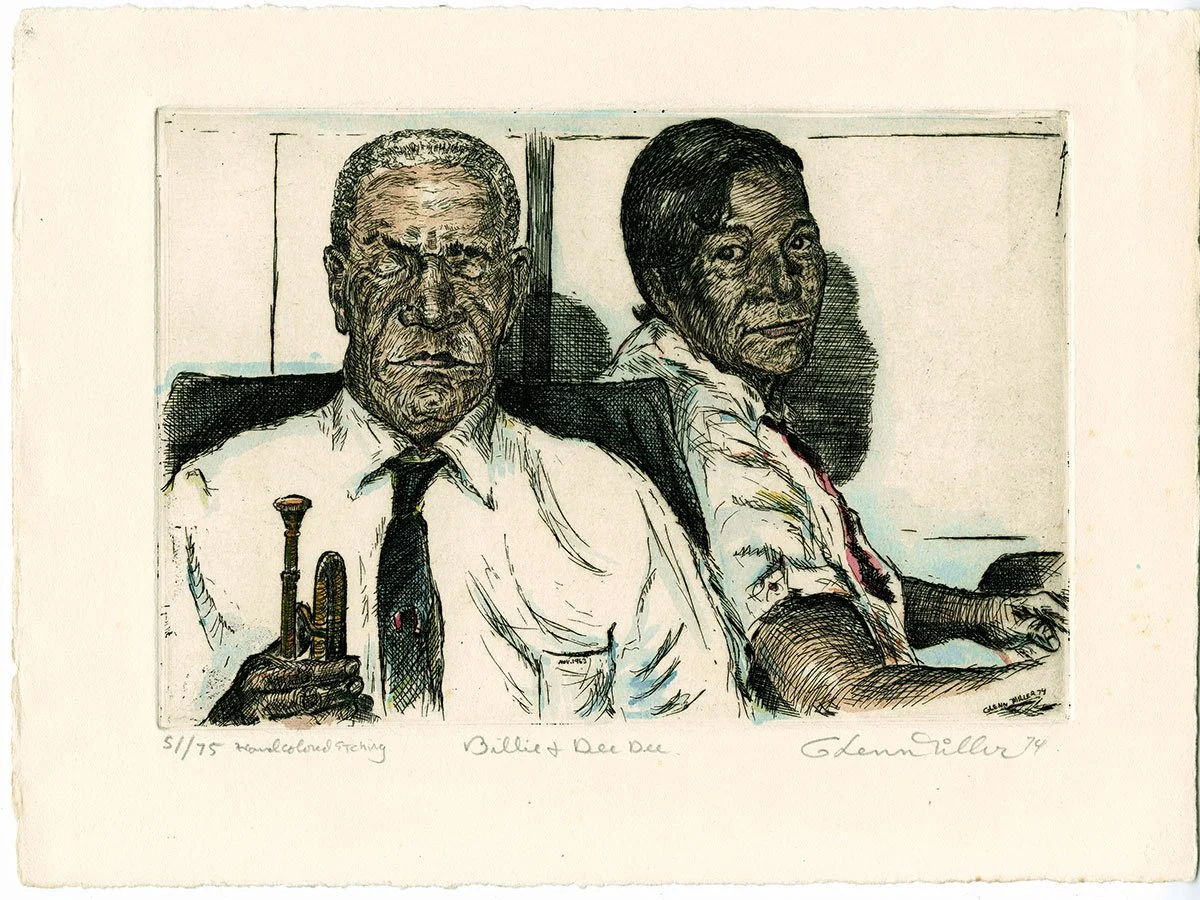

Billie and Dee Dee, hand-colored etching by Glenn E. Miller, 1974. (Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of John Geiser III, 2008.0010.2)

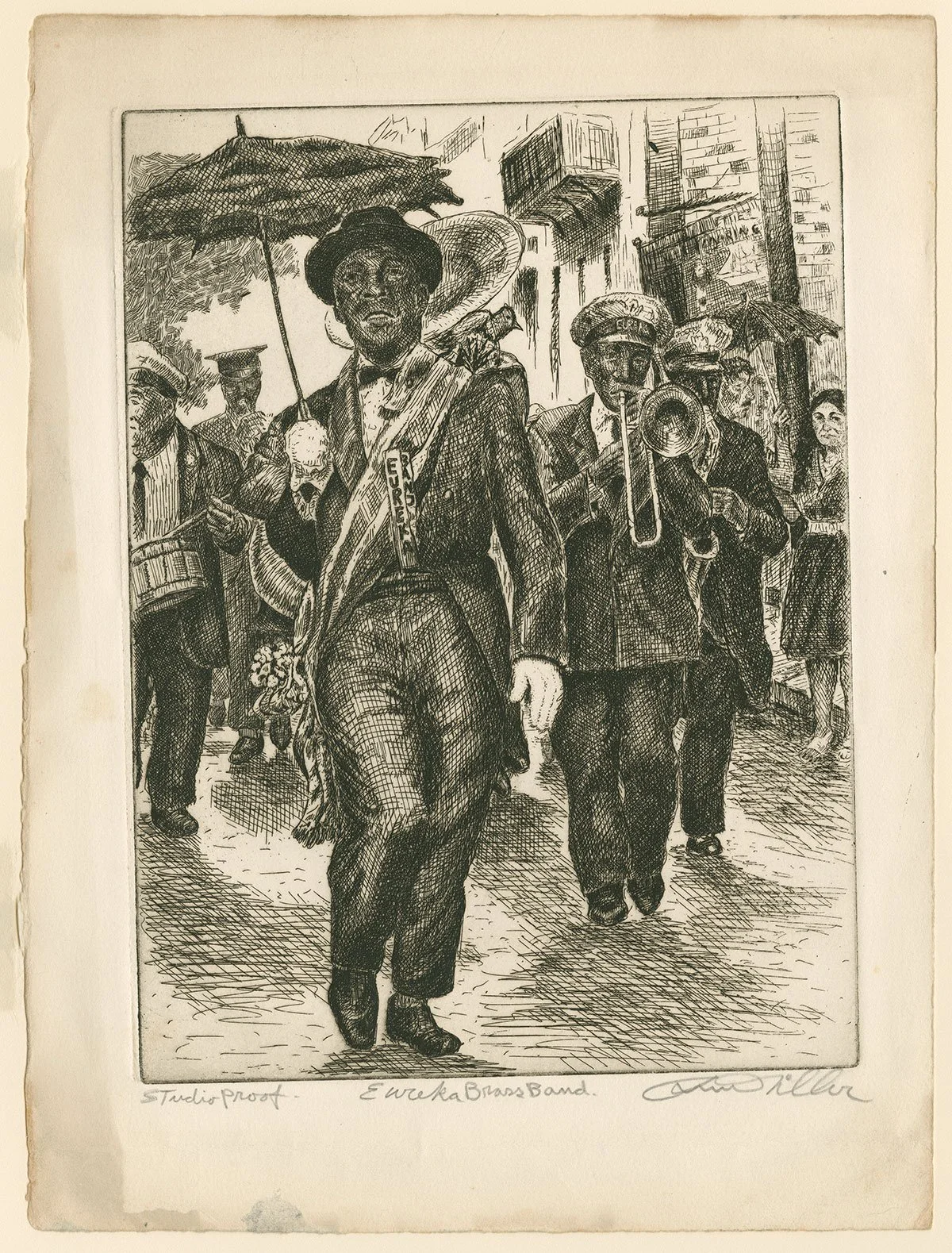

Eureka Brass Band, etching by Glenn E. Miller, 1976. (Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Brother Martin High School, 1992.128.13)

Sweet Emma, hand-colored etching by Glenn E. Miller, 1980. (Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of John Geiser III, 2008.128.17)

But while Glenn still returns to New Orleans on a near-weekly basis, he moved to Ocean Springs, Mississippi, in 1980, home of an artist community anchored by Walter Anderson’s Shearwater Pottery.

“I didn’t like it at first. Quite an adjustment. The quietness is deafening. I want sirens. I want, you know, people screaming.” But he eventually got used to it and has become a cornerstone of the community.

Today, he continues painting and sculpting, while also supporting community issues. The city commissioned him to paint murals across town, and at least two remain: the “Old Fort Bayou” panorama on Washington Avenue (1993) and the mural for Bayou Sporting Goods (1994) on Belleville Avenue.

Recycle art by Glenn E. Miller. (Photo courtesy Glenn E. Miller)

Recycle art by Glenn E. Miller. (Photo courtesy Glenn E. Miller)

And most recently, Ocean Springs commissioned him to create an etching of a downtown panorama. “After they paid me, they noticed – See if you see anything that could be a problem,” Glenn said, as he held out the print to this author. Here and there in the image were tiny nudes.

When the city asked him why he hid all the little nudes in there, he responded, “Why, I do that in all my etchings. You should look closer.”

Etching of Ocean Springs by Glenn Miller