Frenchmen Street Meanderings and Memories

Ben Schenck (reflection) with the Panorama Jazz Band at the Spotted Cat ©Eliot Kamenitz

January 2026Writer and long-time Frenchmen Street bartender celebrates a special occasion - which turns out to be every night on the musical strip.

– by Christopher Louis Romaguera

This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

“We are celebrating a special occasion, for this will probably be the only time that this group of people will all be in the same room together.”

That’s how Ben Schenck of Panorama Jazz Band introduced himself and the band to the crowd after their first song during their set at the Spotted Cat Music Club on a Saturday evening last summer.

I have seen Panorama hundreds of times, and I have worked that shift at the Spotted Cat Music Club hundreds of times, but I don’t think I had ever heard that introduction (and if I did, I had never actually fully processed it). This is why you go to your place of work on your day off.

***

Writer and longtime Spotted Cat bartender, Chris Romaguera, finishing up a shift on a November evening when the Shake ‘Em Up Jazz Band has packed the house.

Frenchmen Street is two-plus blocks, predominantly lined with music clubs. Technically, it sits just outside the French Quarter, but feels like an extension of the Quarter, almost like a phantom limb.

An 1885 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of the neighborhood, showing a section of Frenchmen Street and surrounds. Library of Congress. For a higher resolution on the LOC site, click here.

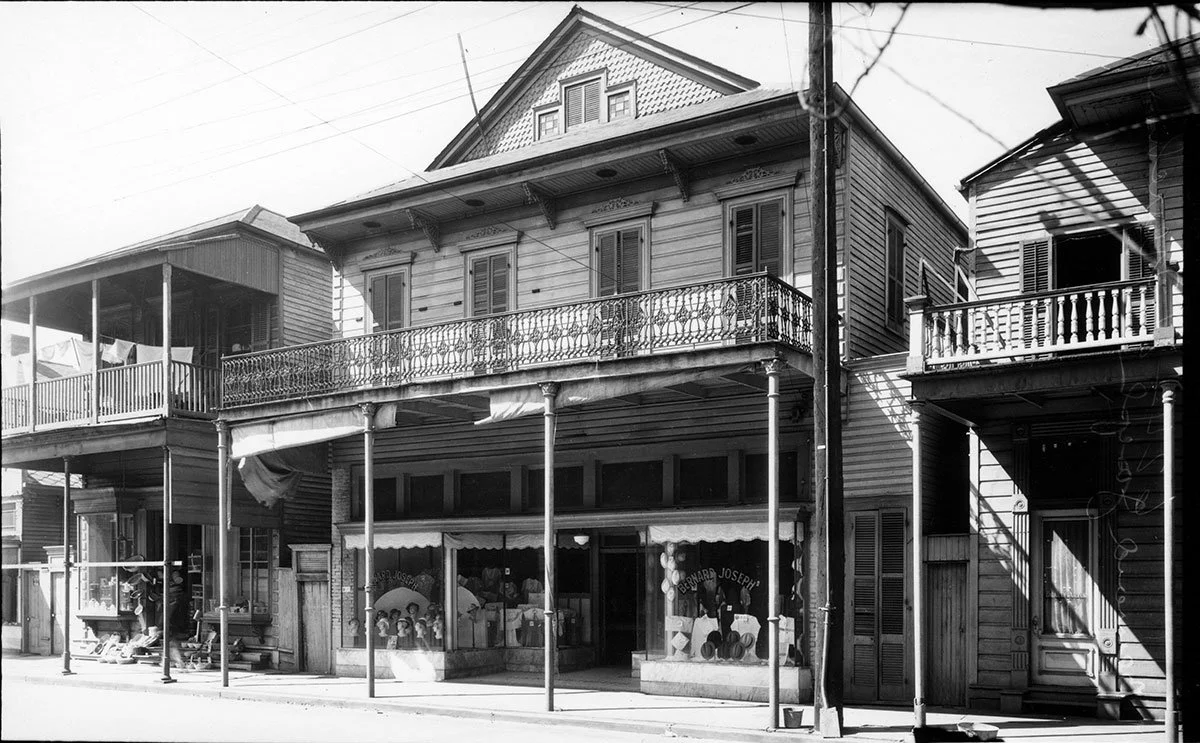

624 - 626 Frenchmen Street, 1925 - 1935, right across the street from the Spotted Cat. The building that once housed Bernard Joseph Department Store has been home to Bicycle Michael’s for over forty years. ©The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.1663

Frenchmen Street got its name after five French men were killed by firing squad after opposing Spanish rule in the 1760s. Bernard Marigny laid out the neighborhood in 1805, loosely naming it “street of the Frenchmen.”

The heart of the street is between Decatur and Royal, bookended by the Esplanade Street fire station and Washington Square Park (where during the afternoon and early evening, a lot of musicians and bartenders will take their coffee and cigarette and food breaks).

During the day, the street is quiet, with most of the business and liveliness happening at Bicycle Michael’s and Ayu Bakehouse. The Spotted Cat opens at two, with most other music clubs opening between five and seven pm. But, while unassuming during the day, that’s the calm before the celebratory storm: the street explodes with culture at night.

Artist Amzie Adams visits with friends on a quiet December afternoon on Frenchmen Street

The corner of Chartres and Frenchmen on a November Saturday evening, 2025.

When I moved to New Orleans in 2011, my first drink and show in town was on Frenchmen (then my second, then my third, etc.) and my first job in New Orleans was on Frenchmen Street (then my second, then my third, etc.)

When I first got here, people often talked about the Frenchmen of the 1990s, with Café Istanbul, PJ’s Coffee (later Café Rose Nicaud), the Dream Palace and Snug Harbor. About all the Latin and reggae music. I often heard stories about Cubanismo playing at Café Brasil, and about John Boutte singing with them.

***

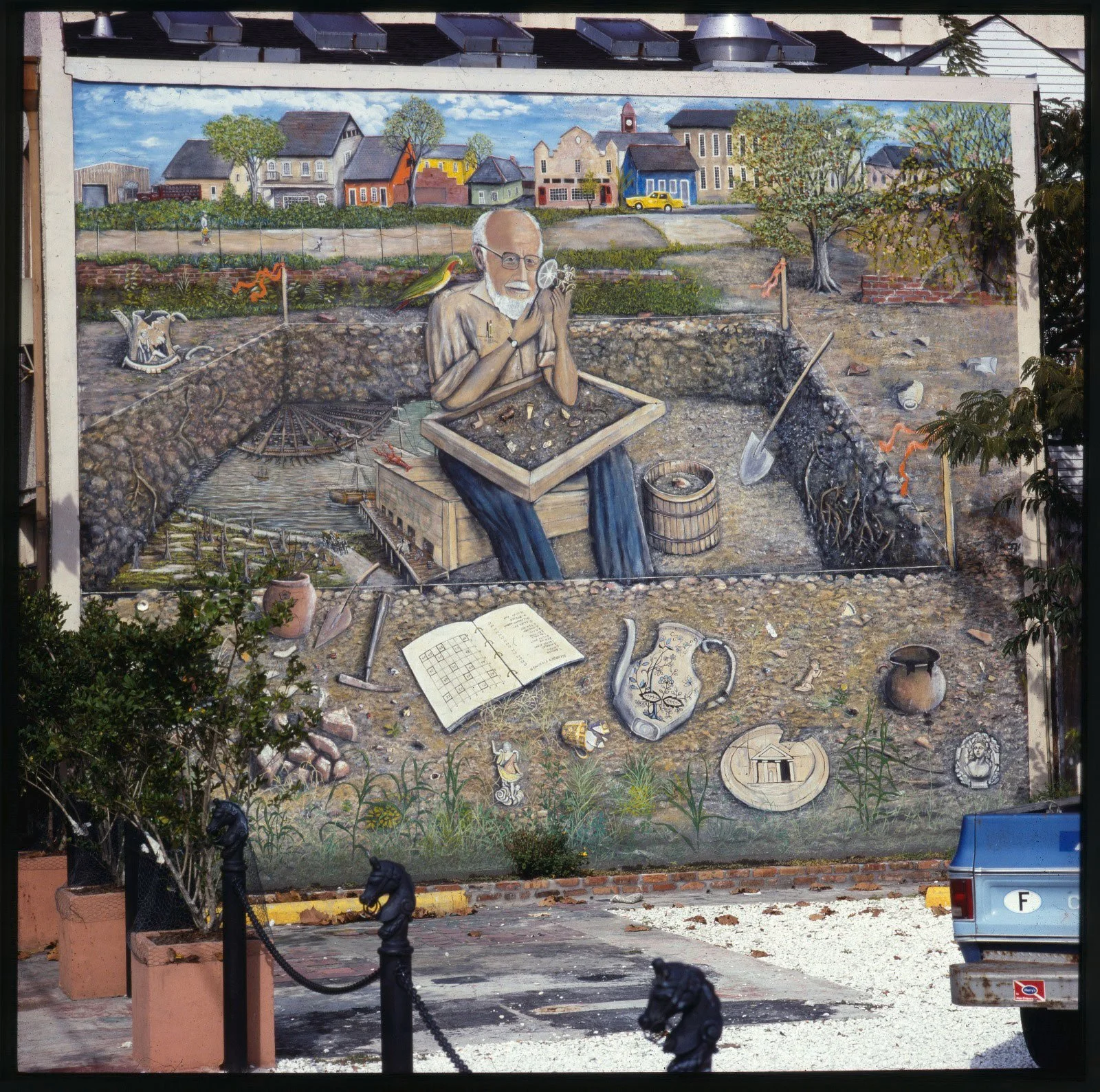

Rain Webb’s “Neighborhood Archaeology” mural, painted in 1986 and photographed by Michael P. Smith the same year. Eventually, the mural succumbed to time and graffiti and the building that now houses Dat Dog was constructed on the lot. Photograph by Michael P. Smith © Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.8.58

The night I heard Ben Schenck’s remarkable introduction, I had headed toward the Spotted Cat at 6pm, just as the sun was starting to set. I wanted to hear Panorama Jazz Band as a patron for a change, not working behind the bar.

Once there, that all too familiar New Orleans thing happened – at the bar I ran into a friend I hadn’t seen in too long. Singer/songwriter Conor Donohue was showing his out-of-town friend, Rachael, around and they had just walked into the club. We listened to the first set, while Rachael and I talked about her beer, Urban South’s Paradise Park.

The Spotted Cat Music Club is open essentially every day besides Christmas. It is a small concrete bar that has standing-room-only more often than not, because three bands play there nightly. When you walk in, the stage is the first thing to your left and the walls are covered with art by local artists – many are renderings of musicians playing their sets here. For those who don’t enter, the big windows allow you to watch the action from the street with a bird’s-eye view.

This drawing by local artist Emilie Rhys of the New Orleans Jazz Vipers playing on stage at the Spotted Cat was used as the cover art for their album, “Blue Turning Grey.” Image courtesy Emilie Rhys

Panorama is one of those fun and prideful bands, filled with an all-star lineup with the likes of Aurora Nealand and Charlie Halloran and too many other people to name. While some Frenchmen Street bands may fall into similar weekly or monthly sets, Panorama keeps theirs fresh. They even have a Song-of-the-Month Club where a seven-dollar subscription gets you a new song they record every month.

If you listen to a Panorama set, they’ll go from originals to Venezuelan waltzes to Eastern European tunes – all within an hour. The band brings together people from all over the world, because everyone will hear something a little familiar, then something a little different; something to make them want to dance or share a drink. And that is part of the magic that made me fall in love with Frenchmen (and New Orleans in general) in the first place.

I spent most of my 20s (and all of my 30s up to this point) on Frenchmen. When I first started working in New Orleans, we spent all our days and nights working, then all our late nights and early mornings listening to music. Some of us even referred to ourselves as the Frenchmen Street mafia.

Bouncing from gig to gig, door guys letting us in, all of us over-tipping, all of us sharing the same $20 bill being the joke. Some of the best shows of my life, I saw for free – or way too close to it.

The crowd outside Cafe Negril on a November Saturday evening.

We savored performances by Meschiya Lake on Tuesday nights (the first gig I ever saw in New Orleans), heard Sarah McCoy’s booming voice without amplification from Washington Square Park and Antoine Diel show-stopping during a sit-in with a rendition of St. James Infirmary at Three Muses, Arséne DeLay with her massive presence singing from bar to bar, Tank and the Bangas or Sam Doores and Hurray for the Riff Raff upstairs at Blue Nile, Glen David Andrews Friday Nights at Three Muses.

I remember watching tightrope walkers and fire-eaters performing where now a giant building stands. And I remember watching when the street would officially close, how if we wanted to see the sun rise after howling at the moon all night, we’d end up at Buffa’s, Mimi’s, or Turtle Bay, bars that had no closing time.

But on this particular night, after catching Panorama, Conor and Rachael and I cross the street to dba. Dba has a different feel to the Cat. You see the stage from the door, but it’s all the way in the back. There are two sides to the club – the left side has a stage and is an amazing listening and dancing room, and to the right is more of a cool lounge vibe.

The stage side of d.b.a., on a November Saturday night, with Richard Pascal’s band on stage.

Cocktails on tap include a Tally Me Banana, which is an Old Fashioned riff with smoke that is delicious. The wood floor gives the club a classic feel, from the dancers to those who just watch the interplay between the musicians and the crowd.

At dba, Jenavieve Cooke and the Royal Street Winding Boys are playing. Jenavieve has a regular Monday day gig at the Spotted Cat which I bartend, “Monday Funday” as she likes to say. They have a large catalog, and she is a natural performer, so you feel in good hands as you listen to them perform.

The band’s sound is classic, and Jenavieve has a way of completely controlling and entrancing a crowd. She sings one of my favorite tunes in her rolodex, “The Song is Ended But The Melody Lingers On,” by Irving Berlin.

I drink a Rhum Barbancourt 15 Years (my favorite Haitian rhum), while Rachael gets a Canebrake from Parish Brewery and Conor orders a Campari soda. One of my oldest and best New Orleans friends, Brian Waitman, is working, and gives me a big hug. We stay for the set, the bar just opening, slowly filling up. The evening glow begins with the finishing sunset.

After Jenavieve’s set, the night is fully upon us. Conor and Rachael decide to go to the Frenchmen Street Art Market, an outdoor art market where local vendors sell handmade jewelry, prints, and an assortment of New Orleans art, with regular vendors including Josh Wingerter and Oscar-nominated documentarian Kimberly Rivers Roberts.

The Frenchmen Street Art Market on a Saturday evening in November

I say hi to my friend, Ramiro Diaz, a Cuban artist, who during the pandemic, painted a picture of everyone hugging in front of the Spotted Cat in an imagined view of what the first day the street and world opening back up would look like.

I have worked the street long enough to see how much it has changed. From having locals as regulars to hearing tourists parrot “where the locals go,” after some pedicabber or hotel concierge dropped them off right at our door, Hand Grenades and Hurricanes in hand.

Online, people argue whether it’s the new Bourbon Street, and whether that’s fair to Frenchmen (or Bourbon). Ten-dollar beer night specials have priced a lot of us out. I used to know the name of damn-near every bartender or waiter on the street.

Now it’s 50/50 if I’ve seen one before. Some of that is getting older, working more and playing less. Some of that is the street growing, and changing. Sometimes, there are fewer hugs than we all hoped for.

The George Brown Band captivating crowds at the Blue Nile (formerly home of the Dream Palace in the ‘70s - mid-’90s) on a Saturday night in November. The incredible ceiling mural that Rain Webb painted on the Dream Palace’s ceiling in the ‘70s has thankfully survived in Blue Nile’s bar area. According to Amzie Adams, the club’s original name in the 1960s was the Dream Castle and at the time, it was the only music venue on Frenchmen Street.

After the Frenchmen Street Art Market, I head to Three Muses, a New Orleans music club and restaurant owned by musician Miss Sophie Lee. Three Muses is sprinkled with a bunch of two and four-top tables, and a cozy six-person bar. They have a full cocktail list and a food menu that includes a bulgogi bowl with Miss Sophie Lee’s family kimchi recipe.

Tonight, at Three Muses, Twerk Thomson has a quartet playing. Twerk is one of my oldest friends on the street, the kind of friend when you both work so much, when your hangs are mostly just during set breaks or “safety meetings,” when one of you encourages the other to take a break and have a drink during your shift.

Twerk has a way of smacking the bass that is aggressive, but somehow soothing – his sets are usually the kind of obscure and perfect soundtrack of exactly what I want to hear when I walk into a bar and want to enjoy a drink.

Trumpeter Gregg Stafford’s band playing at the annual Nickel-A-Dance at Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro with Twerk Thomson on bass. Snug Harbor opened in 1983 to become one of the first music clubs to join the Dream Palace on Frenchmen Street.

I walk inside and see my old roommate, Tony Ratliff and Miss Sophie Lee, the owner of Three Muses. Miss Sophie says it’s almost like 2011 again because she, Tony, and I all lived next door to each other my first year in town.

Before I can even order, a regular from the Spotted Cat sits next to me, then Brian, who’s taking a break from his shift at dba, appears behind me. We joke about how I’m being followed on my day off.

When I walk these blocks, I see the murals of Café Brasil and think of the stories like John Boutté and Cubanismo playing at Café Brasil. I have memories of drinking with Coco Robicheaux before he hit the stage at Apple Barrel, and I’ve had Uncle Lionel dance with my date at the Spotted Cat.

But the here and now is creating its own stories:

I can hear Sarah McCoy’s voice echoing from Washington Square Park; I work shifts where Chris Christy gets rolling and plays in a way where even the most disgruntled of bartenders comments how they feel like they’re in a movie (and he does it three days in a row a week).

Dr. Sick still the national anthem on his saw, and where Cubanismo once played, we now get new Cuban musicians coming into town – like Victor Campbell playing the piano behind his back at Snug, or sitting in for a tune or two at the Cat.

The street isn’t closed off to traffic, even during the busiest times, so drivers often have to navigate slowly around dancers.

Frenchmen Street is special for so many reasons, but Ben encapsulated the most important for me: we’ve all shared this space that maybe we won’t be in again – but damn, we really did all get to share something special while we were here.

And while the song is over for some – and will be for all of us at one point – the melody lingers on as I walk that familiar street, flooded with stories of the times before me and memories of my early days here.

I keep walking until I hear something that stops me in my tracks and brings me back to the present, a moment always deserving celebration.

Chris Romaguera’s September book launch at d.b.a. Romaguera translated the novel Charras by Hernán Lara Zavala. Find it through your local indie bookstore here.