Cover to Cover: Charles Whitfield Richards: The Artist and His Circle

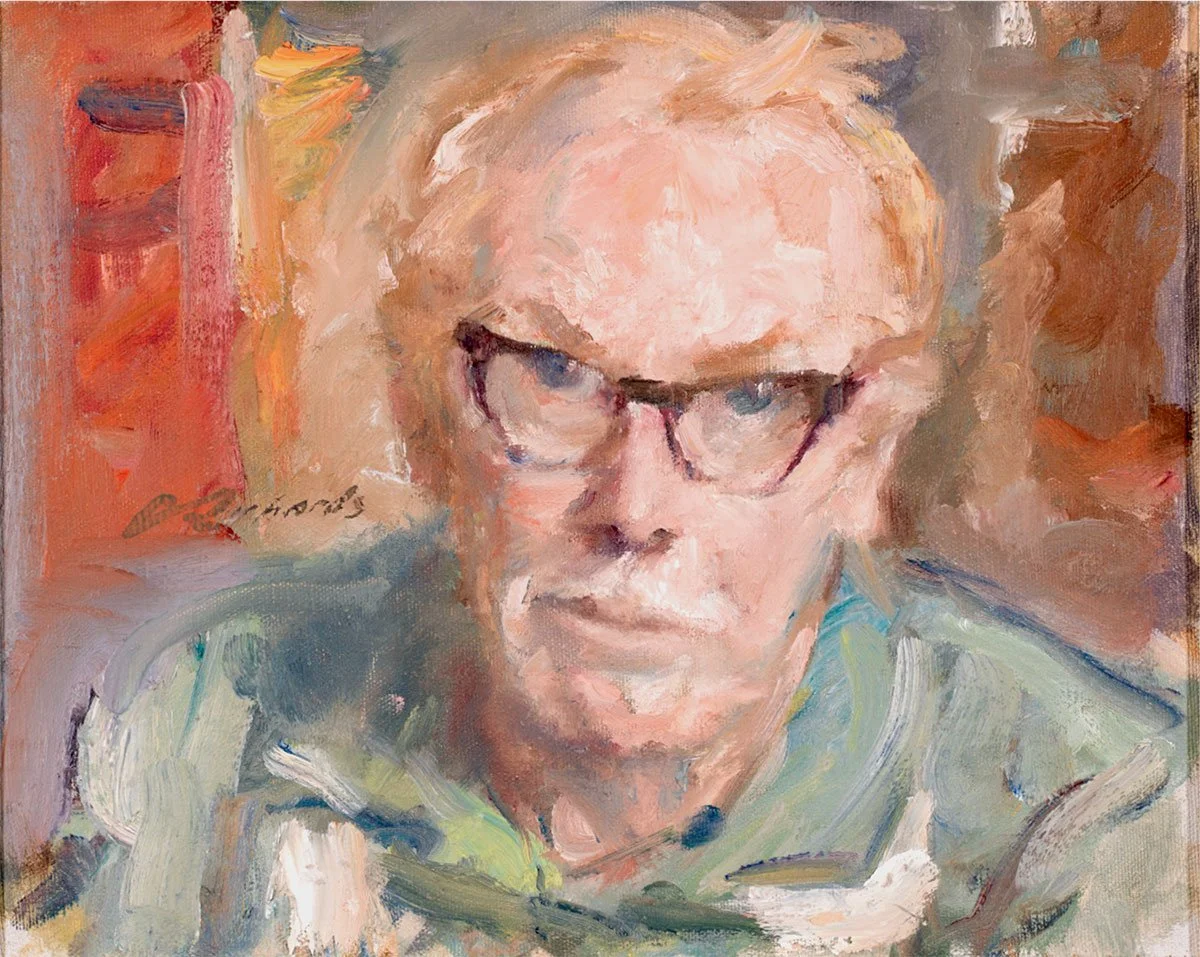

“Self Portrait,” Charles Richards, oil on canvas, c. 1965. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1993.150.2.)

September 2025This new book follows a dynamic young artist into the Roaring ‘20s French Quarter, where its lively Bohemian colony anchors him for the next sixty years.

- by Tom Uskali

This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

Charles Whitfield Richards, artist and journalist, lived in the French Quarter during its heyday as an artists’ haven, from the mid-1920s through the 1980s. Author Michael Warner captures Richards’ life and era through multiple conversations with Richards; those hours emerge in this earnest, thoughtful recounting. Like the protagonist in a Horatio Alger story, Richards embodies the “up by his own bootstraps” American ethos of the early 20th century.

Warner includes a range of drawings, paintings and photographs from Richards’ career. The images demonstrate Richards’ talent, as well as the way he shifted from drawing for publication to being a “fine artist,” a professional tension that shaped his adult years. His crisp style is distinctive through every decade of his work.

Central High School in Memphis, 1923 Junior class. Richards is second from left, top row

Richards was born in Rome, Mississippi, the heart of the Delta, a region of prosperity and hardship. His father, “Mose,” was a small-time landowner and community leader who died when Charles was 14. His mother, Jalie Whitfield Bryant, was from a family with timber land.

The entire Delta saw a shift from lumber to cotton as timber was depleted, and Richards recalls seeing cotton planted in fields where the stumps of cleared forests remained. This was also the height of the Jim Crow era; Richards witnessed a black man shot in the back by his town’s sheriff – for no apparent motive.

With little to keep them in Rome, Richards’ family moved to Memphis in 1919 with his older brother “C.C.,” a practicing lawyer, his mother, and his two younger brothers. At just 15, Richards began reporting for the Memphis Commercial Appeal while still attending high school. Richards dropped out of school weeks prior to graduation and honest-to-God, ran away with the circus in 1924.

As he recounts: “Pitching tents, feeding animals, and especially cleaning up animal output were simply not a step up from newspaper reporting.”

He found his way to the Kansas City Art Institute, where he began studying art in earnest, at least for a few months. There he learned how developing his drawing skills would allow him to market himself as an “artist-correspondent” to newspapers.

Richards enlisted as a merchant sailor in 1925. Arriving in Le Havre, France without a passport, he jumped ship and traveled to Paris, where he briefly lived in the Montparnasse neighborhood and studied at the Académie Delécluse.

Richards worked on figure drawing during his brief time as a student, but soon (early 1926) returned to the United States. He was allowed entry only after his brother traveled from Memphis to New York to vouch for his identity and citizenship.

On his return to Memphis, he finally earned his high school diploma. He had decided he wanted to pursue journalism seriously and was named Art Editor at the Commercial Appeal – at age 21.

Wanderlust and youthful curiosity brought him to New Orleans in July 1927, where he lodged on the top floor of a Rampart Street brothel during his first week in town. His 2-day stint as reporter-artist at the New Orleans States, ended after a dispute over a one-column drawing of boxer Gene Tunney that Richards believed deserved two columns. He was soon writing for the New Orleans Item, where he worked for a time, and which continued to be a landing spot for him in years to come.

A 1929 portrait of Judge Rufus Foster by Richards for the New Orleans Morning Tribune

By this point, the biography was reading like a cautionary tale, but Richards’ moxie or chutzpah propels him with a such dizzying momentum that it caused me to step back and try to enjoy the ride. Given the number of newspapers in print during the early 20th century and their desire for copy (what we’d now call “content”) a talented, albeit restless, young man could likely hop from one newsroom to another.

Bertha Rolfe’s The Quarter’s Book Shop at 632 St. Peter was an important meeting place for writers and artists when Richards arrived. There he met Roark Bradford, journalist and O’Henry Award-winning short story writer. Bradford introduced Richards to the woman who would become his first wife, Marie Louise Reynes, “Lulu.”

And from the little we find out about her, she was indeed a lulu. Their short courtship, cohabitation, marriage, then the revelation of a previous marriage and a 5-year-old child occurs at head-spinning speed.

Richards felt betrayed and “trapped” in the marriage, but in 1928 Richards was offered a position with the New York World, secretly set up by Roark Bradford as an “act of contrition” for introducing Richards to Lulu. While he and his wife seem to have enjoyed their life in the city, Richards soon returned to Memphis, then New Orleans, then Washington, D.C. where he was named editor in charge of American Game Magazine, a position he held until the end of 1932.

Dr. Germain-Ducatel House, painted by Richards circa 1970 - 1975

Fishing Village by Charles Richards, circa 1960 - 1970

“Cypress Swamp,” Charles Richards, oil on canvas, 1969–1978. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Laura Simon Nelson, 1999.118.10.)

Richards and his first wife separated at the end of 1932, and in 1934 began a relationship with Eileen O’Rourke. Professionally, Richards continued his work in journalism, but in 1939 met Morris Henry Hobbs, renowned architectural draftsman who became a mentor to Richards.

The younger artist began studying the craft of printmaking, and “was the moment in Richards’s development when he first broke away from illustrating his own reporting and began to produce art for the sake of the medium.”

By the early 1940’s, Richards was producing etchings and dry point illustrations, including a series for Jeanne deLavigne’s, Ghost Stories of New Orleans. He also began his long-time partnership with French Quarter real estate entrepreneur Eugene Lorenz “Larry” Borenstein at Associated Artists Studio. Their venture continued through the 1960s, but Richards chafed at his patron’s stinginess in supplying artist’s materials.

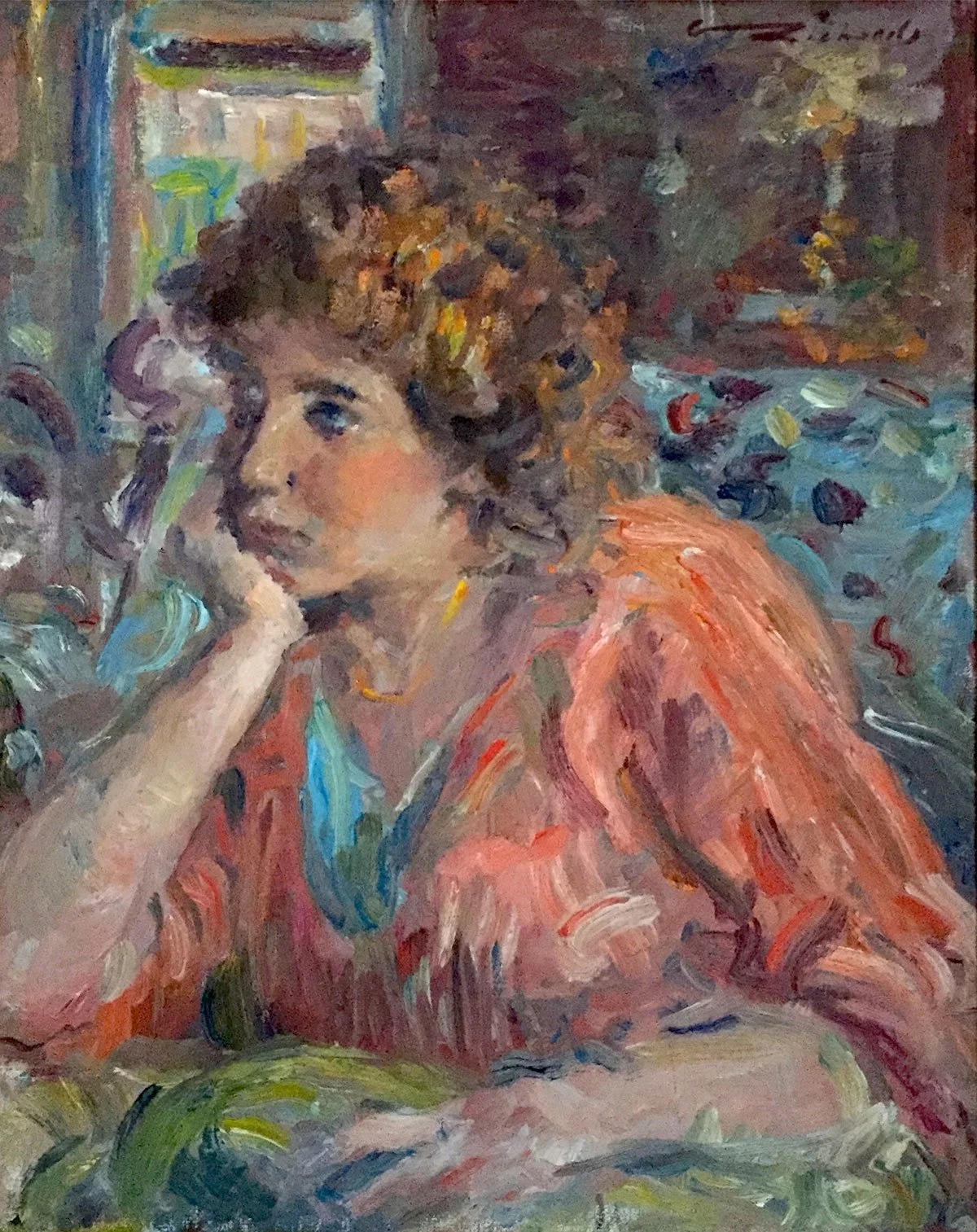

“Martha Gilmore Robinson,” Charles Richards, oil on canvas, c. 1950s. (The Historic New Orleans Collection, bequest of Martha G. Robinson, 1982.241.29.)

“Naomi Gardberg,” Charles Richards, oil on canvas, 1960. (Courtesy Benjamin Franklin High School.)

“Portrait of Laura” by Charles Richards, 1985

Richards separated from Eileen in 1962, began a volatile relationship with Armilla Maria Dunn, and they lived in Houston for a time. He continued to work in portraiture, often feeling like he was “selling out,” and found representation with Peggy Fortier and Jeanne Warner (the author’s mother, also an artist). Their professional support saw him into his later years, and he continued to produce and exhibit his work well into his 80s.

One of the book’s revelations was how sensitive Richards was to negative critique of his work. In a 1948 review of what he felt was a successful opening, the Times Picayune art critic Alberta Collier wrote: “Mr. Richards’ worst failing is his painting of nudes. They are merely blocked out figures with none of the feeling for beauty of the flesh as exemplified in the paintings of Rubens or Renoir and their ilk.”

Warner comments: “Richards was devastated . . . and he felt the floor had dropped out from under him.”

Charles Richards in his studio in 1972, courtesy Mann Gallery

Artist Charles Richards, early 1960s, photo courtesy the estate of Charles Richards

However, Richards was supportive of fellow artists. Vernon Reinike recalls:

“I took some paintings over to him, just walked around the corner, half a block from me or less, and I said, ‘Hey, Charles, what do you think?’ You know, it was one of those deals when you’re not sure what you’ve done. And he said, ‘What are you trying to do?’ I said, ‘Well, you know, I’m trying to finish. I’m trying to come to the finish.’ But he just looked at them for a while. And he finally looked at me and kind of smiled, and he said, ‘You know, sometimes you really don’t have to do much more.’ And I said, ‘Oh.’ And the more I looked at it, the more he was right. I mean, the reason I couldn’t see what to do was because there wasn’t much more to do. . . . Whatever he said always turned out to be positive. Whether your work stunk or not, it turned out to be positive.”

Leaning Nude by Charles Richards, 1970s, conte crayon on paper

Nude study from 1969 by Charles Richards, conte crayon on paper

In 1987, Richards, along with Enrique Alferez, was feted at the Contemporary Arts Center’s Sweet Arts Ball. The event merged two artistic eras, as a new generation of local artists flourished (Robert Gordy, George Dureau, Ida Kohlmeyer, Lin Emery, et al) and should have been a happy event. However, Richards got into a scuffle with Alferez over a commission he lost decades prior, and “flew into a rage.” The two artists never spoke again.

The artist we meet in this biography is mercurial and passionate. Michael Warner’s patience as an interviewer allows Richards to share his emotions, aspirations, and misgivings. The numerous drawings, etchings, and paintings are a highlight of this work, and give readers a sense of Richards’ talent.

As a biography, the work is a melange of overlapping stories told by Richards, framed by vignettes of significant people in his life. For the reader, more “interweaving” of the various figures who made up Richards’ circle would add depth and a richer sense of context. Nevertheless, Richards’ talent seems still underappreciated in the New Orleans art scene; it is our good fortune to have this book to bring him back into the conversation.

Treeline by Charles Richards, 1970s

Charles Whitfield Richards: The Artist and His Circle

By Michael Warner

University of Louisiana Lafayette Press 2025

Charles Whitfield Richards (1906-1992)