Cover to Cover: New Orleans (1970 - 2020), A Portrait of the City

The book’s cover image, copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

September 2025A new book by writer Dalt Wonk and photographer Josephine Sacabo unflinchingly documents a five-decade love affair between the two artists and their abiding passion for New Orleans.

– by Richard Goodman

This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

No one should come to live in New Orleans unless they have a high sense of adventure and an unshakable belief in good luck. There is no better proof of this than in the pages of Dalt Wonk’s book, New Orleans (1970-2020): A Portrait of the City, with photographs by Josephine Sacabo. Wonk and Sacabo are a married couple who came to New Orleans in the early 1970s and stayed. Adventure and good luck confronted them everywhere.

The book begins with how Wonk and Sacabo arrived in the Crescent City in 1973. The story is told in prose that brims with delighted, boyish naiveté. It’s as winning an account I’ve ever read about someone encountering New Orleans for the first time.

Josephine Sacabo and Dalt Wonk

Click here to order the book from Luna Press

Written in short-sentenced, first-person, wide-eyed prose, the reader accompanies the young couple on those first adventurous weeks and then months in the French Quarter—a place Wonk calls “enchantment” – of fifty years ago.

When an adventure is full of twists and turns and setbacks, not to mention shortness of money, as was theirs, I want to be in the company of people who take it with shrugged shoulders, letting the water of rejection and mishap fall off their backs, bolstered by the fact that they’re in love and having the time of their young lives and that they’re 100%, indisputably alive. People like Wonk and Sacabo.

As they try to find a way to pay the rent and then, awaiting the birth of their first child, contemplate how they will support their young family, luck encounters Wonk and Sacabo in the form of an apartment in the Spanish Stables, in a sweet part of the French Quarter, with a landlord who genially accepts the fact that they will soon have a baby and, even, that they have a dog. This is where they will live for the next twenty years.

Wonk decides, spontaneously, that he will become a journalist, without anyone asking him. Sacabo decides to be a photographer with the same lack of a formal invitation. Despite a few missteps, Wonk finds a place for his words in local publications—and Sacabo for her photographs—and they’re off. (Sacabo, it should be noted, eventually became a celebrated photographer whose work is in the collections of major museums, here and abroad. Wonk is an author and playwright whose works have been performed here and abroad as well.)

Dalt, (center) and Sacabo in a play

Dalt, Josephine and Iris, their daughter, who grew up in the old Spanish Stables on Governor Nichols Street in the French Quarter

The majority of the book consists of the articles Wonk wrote over the years, mostly in the 1980s and 1990s, for local publications on a wide range of places, personalities and events. There is love, death, crime, passion, eccentricity, and plain strangeness in these pieces. As well as sadness and tragedy.

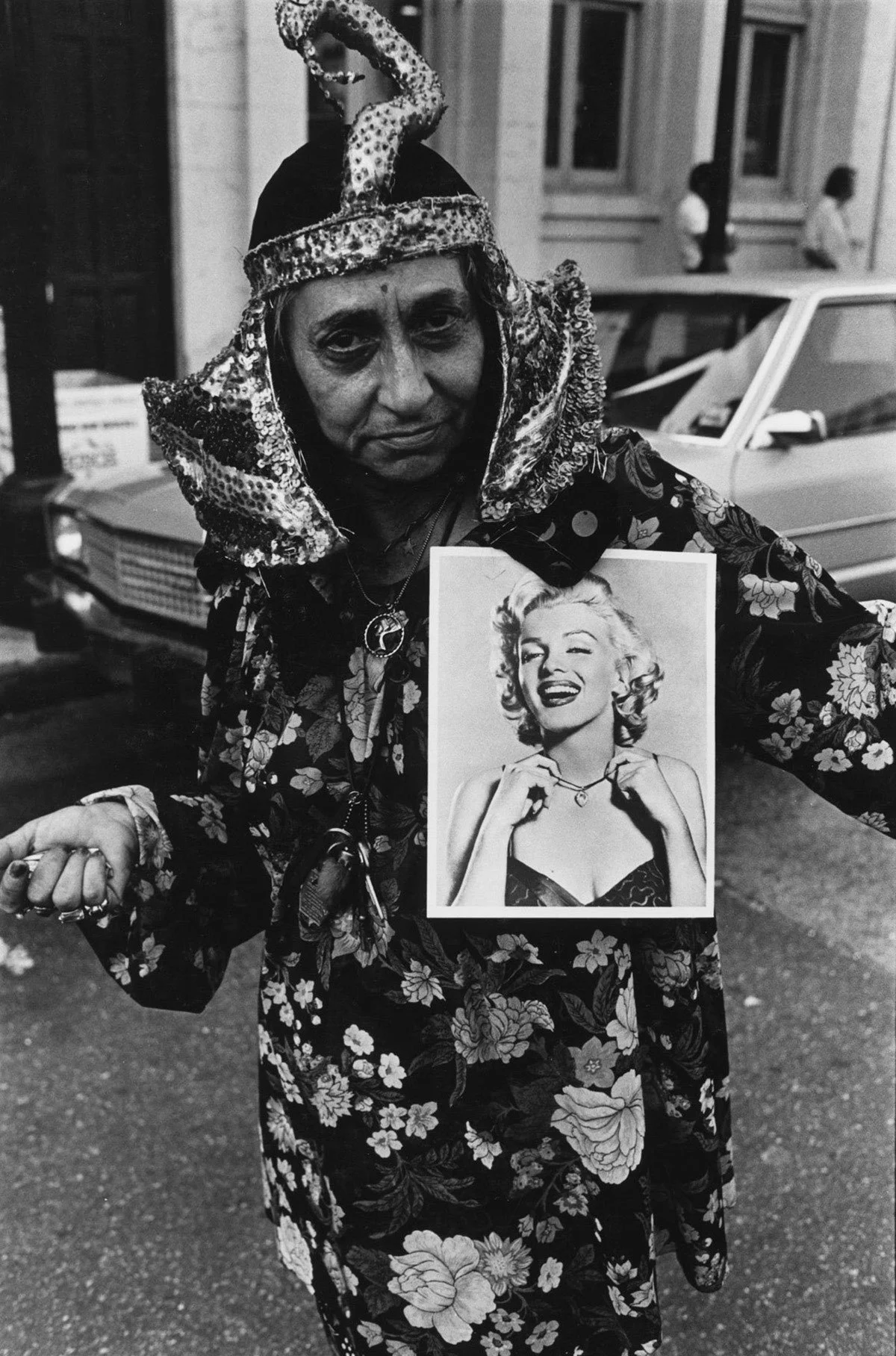

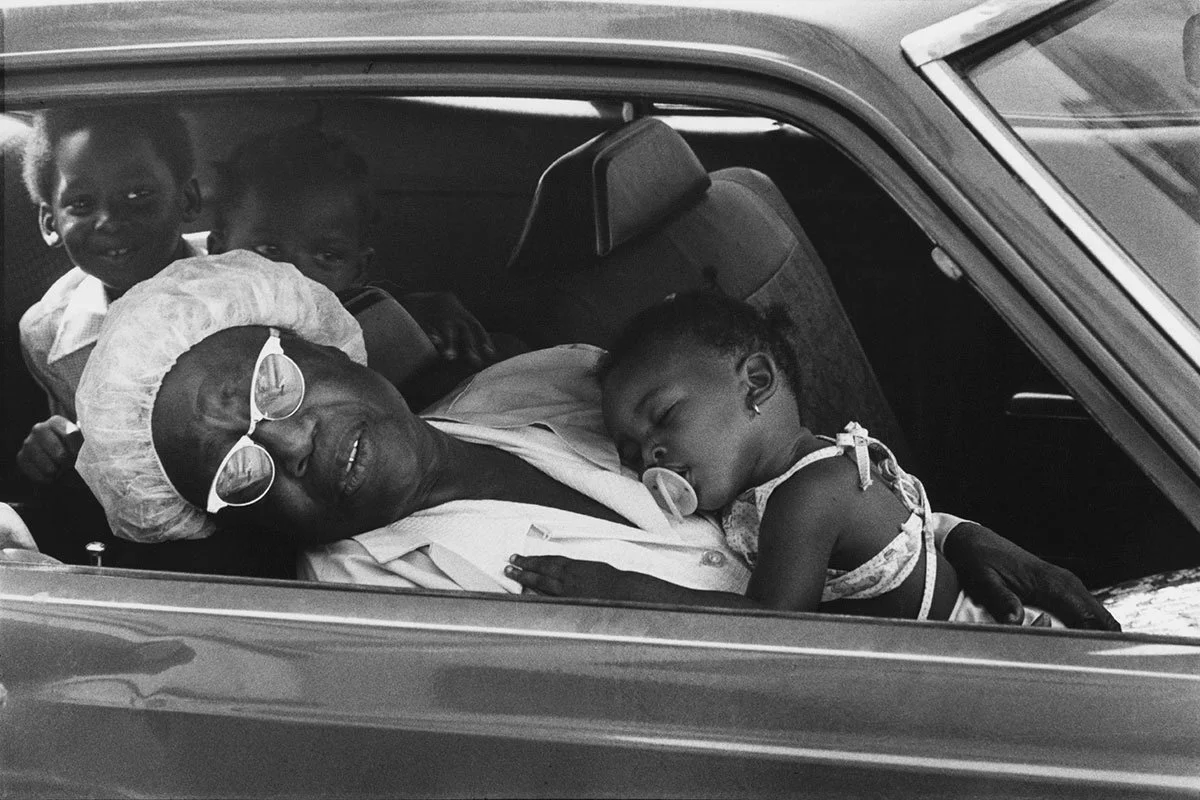

There is also a section in the book devoted to 35 of Josephine Sacabo’s black and white photographs from 1970-2000, titled, “Sanctuary.” The uncaptioned photos are mostly of people, all sorts, characters in everyday guises, ordinary people you might encounter in the New Orleans of fifty years ago. The photographs have an unvarnished directness to them, influenced, as Sacabo herself says, by Robert Frank among others.

There is a Weegee-like sense to this book and to its prose. Wonk turns his eye to anything and everything this city has to offer, trains it on murder and chicanery, on the weird and eccentric, on the everyday, capturing moments in black-and-white-tinted prose, with tabloid-like titles or subtitles: “The Honeymoon Murders,” “Where Death Delights to Serve the Living,” “The Chaplain of Violence,” “A Private Eye in Bridal Gown.”

Ruthie the Duck Lady, copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

The reader gets the same unfiltered eye, unflinching and uncensored, as that of the famous New York photographer from the 1930s and 40s. How much different in style and boldness are Wonk’s titles than Weegee’s? “Balcony Seats at a Murder” “Self Portrait in Police Van,” etc. There is an appealing element of blunt melodrama, of unapologetic rawness, in Wonk’s prose that you find in Weegee’s photographs.

I personally prefer Wonk’s longer pieces, where he is able to treat his subjects with depth and amplitude and tell a story that resonates beyond the temporal restrictions of daily journalism.

“The Fall of the House of Orchard,” for example, is the story of the sad and tragic decline of two sisters and the doomed house they lived in. It’s a Gray Gardens-like tale that is just as memorable as that celebrated documentary, but far darker. It stays uncomfortably in the mind after reading.

The two women live alone in a house that is proclaimed by the world to be haunted and soon becomes a stopping point and target for every bored, mindless person with a taunting nature and, often, a brick in hand. This story leaves you with a sense of how often we fail those who are weaker than we are and more vulnerable. It stays under the skin and rightfully makes the reader feel a vicarious sense of guilt at not rising up to protect these harmless and defenseless women. In that sense, the story is timeless and timely.

This story, and others, illustrate an attractive aspect of Wonk’s writing. He may have been a journalist with a journalist’s charge to be honest and objective, but he openly cares about his subjects. He treats them kindly in his stories, sometimes with bemusement, sometimes with sadness, but always caringly, even tenderly. He writes with humor, too, a lightness that is refreshing.

Published in large format, the volume shows the care and design of a fine press throughout, which adds to its allure.

copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

Anyone who is a fan of A Confederacy of Dunces will also want to read the long, intimate and melancholy piece, “The Bitter Triumph of John Kennedy Toole,” published in 1981, the year John Kennedy Toole’s posthumously published book won the Pulitzer Prize.

Wonk interviewed Toole’s mother, Thelma, and the piece has extensive stories and insights from her. She was her son’s tireless advocate, and there is the picture in the mind of her carrying her son’s unwanted manuscript under arm from door to door trying to get it read and published. She finally knocked on Walker Percy’s door, and he was able – not without difficulty – to get the book published.

This story of Ken Toole—as he is called in the article and the name by which he was known to family and friends—is the story that will forever be a sad one. Toole died without ever seeing his book in print, much less walking by a statue of his now-celebrated main character, Ignatius J. Reilly, planted securely on Canal Street. I suggest Wikipedia revise their piece on Toole to include some references from Wonk’s fastidious study of a writer and his grieving mother.

There are vivid portraits of denizens of the city as well here. “The Last of the Batture Dwellers” is one of my favorites, a portrait of life in a sort of shantytown on the Mississippi in uptown New Orleans.

And not all stories take place in New Orleans. In one, the couple travel to Laredo, Texas to interview a proponent of something called Mind Control. It happens that Sacabo was born and raised in Laredo, and there are overlapping relationships. The interview does not end well.

I would suggest perhaps the best way to read this book is as an anthology. I found myself enjoying it most in small doses. I would open it and read three or four of Wonk’s pieces, as you would an anthology of poetry or short stories, then put it down only to come back to it a day or so later, letting those three or four pieces percolate in my mind on their own.

copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

copyright ©Josephine Sacabo, courtesy Luna Press

There is no overriding arc to this book. You will not lose its essence if you read a piece from the beginning and then one from the middle. Or vice versa. Anthologies give you the freedom to be random and spontaneous and to be guilt-free about moving on; if you don’t feel like reading this particular piece at this particular time, don’t. There’s another one waiting on the next page.

If there is a theme to this book, it would be loss. Like so many of us of a certain age, we have told ourselves we won’t bore our children or friends with “the way it used to be” or “in my day” stories.

Then we do. Because in some cases, we really do believe those times were better, more interesting. Wonk is unapologetically one of those people.

You should have been there, Wonk loudly declares. “When it comes to the French Quarter,” he writes, “it was the oddball, bohemian French Quarter that drew me and Josephine like a magnet.

“That French Quarter no longer exists. It’s been transformed, by the alchemy of greed, into a theme park version of itself.”

New Orleans (1970-2020) is a way to time travel, to go to a place that no longer exists, with Wonk as your genial and sensitive guide, to see a vanished New Orleans, and, most importantly, the oddball, bohemian French Quarter that he laments.

The truth is, you can go home again – at least in a book.

New Orleans (1970-2020): A Portrait of the City

by Dalt Wonk

with photographs by Josephine Sacabo

Luna Press 2024

Dalt Wonk and Josephine Sacabo in the courtyard of their French Quarter home. ©Chris Granger