The Assunto Brothers and Louis Armstrong: How New Orleans Jazz Pushed Jim Crow’s Envelope

The original Dukes of Dixieland recording with Louis Armstrong. Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum.

July 2025In the 1950s, two talented young brothers rocket from a Bourbon Street bar to Carnegie Hall, eventually recording with one of their childhood heroes - despite the South’s repressive Jim Crow laws.

- by Bethany Ewald Bultman

This column is underwritten in part by Lucy Burnett

"The Dukes of Dixieland, who I think was the youngest group to leave New Orleans, was the first white band whom me and my band played on the same stage with, which was a great thrill to me.”

– Louis Armstrong (Louis Armstrong, In His Own Words, edited by Thomas Brothers, Oxford Press 1999.)

Until the late 1960s, Bourbon Street was so segregated “whites only” signs were redundant. Although Benny Goodman’s big band began including both Black and white members in the 1930s and other bands followed suit, the South’s Jim Crow laws demanded segregation in music – as in all other aspects of society – for decades longer.

Then, in the 1950s, two grandsons of Sicilian immigrants, Fred and Frank Assunto, aligned with their trumpet-playing hero, Louis Armstrong. All three were New Orleans natives. And by playing New Orleans-style jazz together, they musically pushed back against the insidious repression.

Trumpeter and bandleader “Kid Thomas” Valentine’s Dance Band was based in Algiers on the west bank of the Mississippi. At dances the going rate for musicians was $3.00. The leader got $4 and a buck for incidentals. Courtesy the William Russell Jazz Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection with appreciation to the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund.

By the 1950s, New Orleans’ population tipped the scales at just over 570,000 citizens, one-third of whom were African Americans. Many locals would argue that Dixieland - now called traditional jazz – was on its last leg. The few remaining, aging jazz legends weathered oppression and poverty to keep the traditions alive.

White audiences going to hear music in Black clubs were sometimes arrested, making it particularly difficult for musicians to make a living. For instance, according to Richard Campanella in A History of Bourbon Street (LSU Press, 2014), nine white patrons were arrested in 1952 at the Dew Drop Inn, an African American club.

Black musicians had to hustle for gigs at white clubs, toting their bands’ signs from gig to gig. Often, they earned less for four hours performing than the cab fare to take them back home after the event.

As the economics of “bump and grind” edged Dixieland off Bourbon Street, an unlikely champion emerged in the late 1930s. Hypolite Guinle was a down-on-his-luck ex-boxer turned cab driver known by his moniker “Hyp.” Hyp opened the Famous Door on the corner of Bourbon and Conti Streets in 1936.

“Hyp stocked The Famous Door’s dance floor with the most beautiful fallen women in the South and hired the top hootenanny jazz acts in the world to play wild, loose and fast.”

– Kent “Frenchy” Brouillette, former boxer and author of Mr. New Orleans: The Life of a Big Easy Underworld Legend

The Famous Door was around the corner from the Ringside Lounge. It was owned by one of America’s first sports super stars, Pete Herman (Gulotta), the former world boxing champion. In 1946, Pete Herman and his Ringside Band greeted Jimmy Dorsey’s orchestra at Moisant Field (now The Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport). Courtesy the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum/New Orleans Jazz Museum.

As Brouillette recounted in his memoir, Hyp soon earned a reputation for excess – quite the distinction on a street synonymous with vice. Consequently, by the early 1940s, Hyp found himself deeply in debt to “Silver Dollar Sam” Carollo, the ruthless Sicilian-born New Orleans bootlegger, loan shark, and slot machine kingpin. He was not a man to be trifled with.

Everybody on Bourbon Street knew why. In 1929, mobster Al Capone took the train from Chicago to add Bourbon Street to his bootleg kingdom. After a tip, “Silver Dollar Sam” dispatched some ex-boxers from the French Quarter to the Union Passenger Terminal. When Capone’s bodyguards stepped off the train, Carollo’s henchmen broke their fingers with hammers.

Capone remained on the train until it returned to Chicago.

With Carolla’s finger-breaking enforcers breathing down his neck, Hyp had to walk the plank one way or the other. Thus, he got “leg shackled” to a feisty Plaquemine’s Parish widow who entered their union with a stash of cash long hidden by her late bootlegger husband. Genevieve Caserta DiCarlo Guinle had another physical attribute noted in a few Sicilian women: Eyes in the back of her head.

The new Mrs. Guinle immediately took possession of The Famous Door’s books. Now that Hyp worked for his wife, he could promote Dixieland jazz full time. After each hourly, forty-five-minute set, Famous Door audiences were enticed up on the stage for a rousing second line. The house band was led by trumpeter Joseph Gustaf “Sharkey” Bonano and his Kings of Dixieland.

The Famous Door in 1950, courtesy the Vieux Carré Virtual Library

The Famous Door in 1950, courtesy the Vieux Carré Virtual Library

By the late 1940s Joseph Gustave “Sharkey” Bonano and his Kings of Dixieland ruled Famous Door stage. Sporting his signature bowler hat, Bonano joked, danced and pranced, sharing the joy of Sicilian flavored New Orleans-style jazz. Edmond Souchon, MD, Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club of the Louisiana State Museum/ New Orleans Jazz Museum.

In his 1954, 1960 and 1963 recordings, Bonano flaunted the race laws: The albums, released by GHB, were originally recorded by Joe Mares for his Southland label. Mares was a master at bringing together Black and white musicians at a time when they could not legally perform together in public in the South. In this case, Louis Cottrell was the President of the Negro Musicians Union and Paul Barbarin was Danny Barker's uncle. Album cover courtesy of the George H. Buck Jazz Foundation.

By the 1930s, John Matassa and Joe Mancuso, J&M Amusement Service (838-40N. Rampart), supplied coin-operated jukeboxes, on a commission basis, to bars and restaurants. John’s son, Cosimo, became convinced that he could expand profits by recording the music they stocked on the jukebox. Part of Cosimo’s formula was to give Jim Crow the heave-ho. With Permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

The son of Sicilian immigrants, Bonano grew up at Quarella’s – a dance pavilion in the Milneburg area of Gentilly, near Lake Pontchartrain. Young “Sharkey” picked up technique by following “King” Joe Oliver in brass band parades. Even Bonano’s band name was an homage to Oliver.

During the jazz renaissance (1920-40s), “Sharkey” toured the world. By the mid-1940s, his radio and television appearances made The Kings of Dixieland at the Famous Door a tourist destination.

Two of “Sharkey’s” ardent fans were the gangly, teenage Assunto brothers, Fred and Frank. The Assuntos grew up Uptown, far from the shenanigans of Bourbon Street, in a musical household steeped in Sicilian cultural traditions.

In 1947, Fred graduated from the all-boys St. Aloysius on Esplanade and Rampart (1869-1969) where he was the leader of their marching band. Once he entered college at Loyola, he performed with the Loyola Symphony Orchestra. His brother Frank attended Redemptorist High School, where the boys’ father, Jacinto “PaPa Jac” Assunto, (born 1905 in Lake Charles) was band leader.

Holding a B.A. from Tulane University in Business and a degree in Music Education from Loyola, Jacinto looked more like an accountant than a musician. But by night, Jacinto made a name for himself playing his valve slide trombone with two bands in the pits at the Orpheum and Lowe’s State.

Fred (Frederico) Assunto trained as a master tailor in Paris, before immgrating to Ellis Island. From New York he came south to join his family in Lake Charles, La. Jacinto “PaPa Jac,” father of Fred and Frank, was the eldest of the four children of his Sicilian immigrant parents. The youngest son was Joe Frank Assunto who later owned "On Stop Records" on Bayou Road near the track. Henry Roeland Byrd, "Professor Longhair," traded janitorial services for free recording time. On Feb 4, 1967, Joe Assunto rode on the Captain Joe's S.S. Endymion float as the Mid-City Krewe's first captain. With permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

Sicilian immigrant, Fred (Frederico) Assunto ( far left with mustache) played piccolo and accordion in Professor Joe Rosato’s Military Band. Rosato was an Italian immigrant who became a music professor at Tulane University. With Permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

In the early ‘50s, Loyola University sponsored a talent show, which resulted in Jacinto’s sons winning a slot on the Ted Mack Amateur Hour’s national tour.

There, Fred, determined to study law at Loyola, fell head over heels in love with the adorable, fifteen-year-old Betty Owens, a hillbilly crooner in a rival band. Fred Assunto decided the law could wait. He recruited Betty to spice up their traditional jazz band. Years later they would marry and Betty would become known as “the Duchess.”

Budding musicians Frankie (b. 1932) and Fred (b.1929) Assunto outside of their home at 2621-23 General Taylor. Freddie always preferred to stick to “the trad jazz dozen” while Frankie liked to twist popular songs into souped-up Dixieland-style arrangements., © Jacinto Assunto

The Assuntos’ buddy, Pete Fountain (front row with clarinet), proved to be the perfect guide to show the Assuntos the ropes on Bourbon Street.

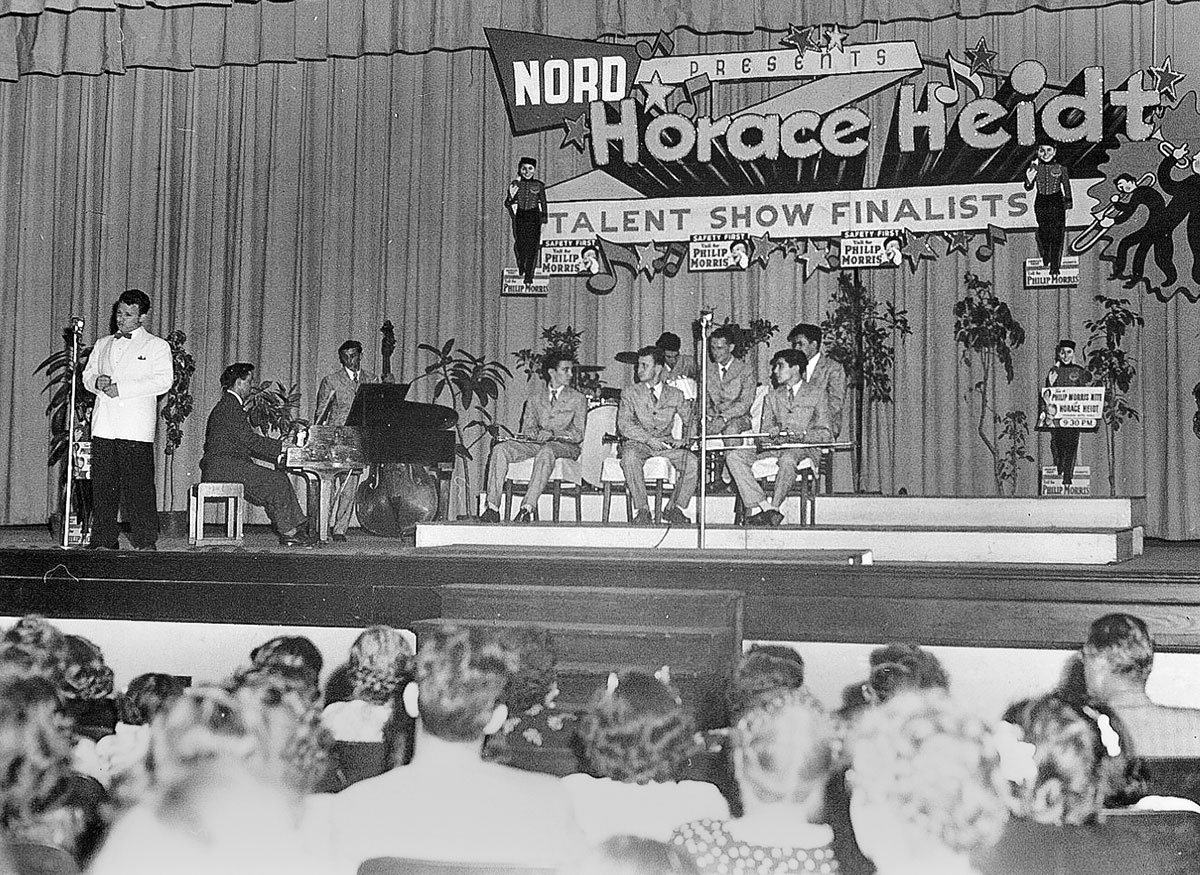

On February 20, 1949, the Assunto brothers’ Junior Dixieland Band won the top prize in Horace Heidt’s “Pot of Gold” radio show’s talent contest. The brothers on trombone and trumpet were joined by a buddy from Warren Easton High School on clarinet, Pierre Dewey LaFontaine, Jr. Known professionally as Pete Fountain, the teen was already earning over $100 per week playing jazz on Bourbon Street. With permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

As the national runners-up in Horace Heidt’s “Pot of Gold” radio show, the two brothers won $500. The talented boys used their prize money to join the American Federation of Musicians Local 176. (The Black musicians’ union, Local 496, did not merge with the white union until 1971.)

They also needed to “pay their dues” at the New Orleans Jazz Club, NOJC (formed in 1948, it’s now the country’s oldest jazz club). Their father, Jacinto, was one of its charter members. The group’s goal was to foster appreciation for New Orleans-style jazz.

When female Dixieland bandleader Sweet Emma Barret had the money she carried in brown paper bag stolen, the New Orleans Jazz Club hosted their first benefit concert. It was so popular it became a weekly event.

Sweet Emma (Barrett) 1962 business card, courtesy the William Russell Jazz Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection with appreciation to the Clarissa Claiborne Grima Fund.

“I don’t like to hear someone put down Dixieland. Those people who say there’s no music but bop are just stupid; it shows how much they don’t know.”

-Miles Davis (Pat Harris, Downbeat’s first interview with Miles Davis, January 27, 1950)

The Assuntos’ big break came a few months after Frank graduated from Redemptorist. Sharkey and his Kings of Dixieland were leaving on tour. Hyp decided to hire the kids to fill in for 3 weeks. In homage to Bonano, the young Assuntos called themselves the Dukes of Dixieland.

On December 18, 1950, with Frank on trumpet, Fred on trombone, and Pete Fountain on clarinet, they took over the Famous Door stage, ramping up “the hallowed Dixieland dozen” tunes to breakneck speed.

In August 1950, the NOJC invited the 18-year-old Frank (with a baby face he only had to shave twice a week) to serve as the “maestro” for the club’s second open-air jazz fest in Beauregard Square (Congo Square today). (Tommy Griffin, “Lagnaippe”, The Times Picayune, August 25, 1950)

At the time, the new song “Bourbon Street Parade” by Paul Barbarin was catching on in the city. Jacinto knew Barbarin from the pit at the Orpheum, so the Dukes of Dixieland asked the composer for permission to perform the song at the Famous Door and to record it. As a result, Barbarin became one of New Orleans’ first Black musicians to earn “mailbox money” for royalties.

Adolphe Paul Barbarin with the nineteen-year-old Frank J. Assunto. Paul Barbarin’s “Bourbon Street Parade” (1949) extolled Bourbon Street as a playground of delights at a time when only Black musicians carrying instruments were allowed on Bourbon Street. In 1951, the Dukes became the first band to record it. The song became the most popular of the collabortions between Armstrong and the Dukes, earning Barbarin more royalties from it than he ever earned as a musician in segregated New Orleans. Photograph © Jacinto Assunto, with Permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

On May 13, 1952, Louis Armstrong and his All-Stars played at the Municipal Auditorium (Armstrong Park, today). Knowing that the jazz legend was prohibited by segregation from coming to Bourbon Street unless he was there to perform, the Assunto brothers raced to the auditorium between their sets at The Famous Door to pay their respects.

It turns out, Armstrong was already hip to the Dukes, having included their early local recordings on his private reel-to-reel tapes. Armstrong scholar Ricky Riccardi writes that he told the young musicians he looked forward to their crossing the Mason-Dixon line so he could play with them.

The Dukes of Dixieland held the Famous Door spotlight for nearly four years, but they saw the writing on the wall. The “short, bald and very heavy, Hyp,” was a certifiable “wildman.” The backstage leaked when it rained because Hyp had shot his gun through the ceiling.

One time, the band had to keep performing even though the famed Guy Lombardo was sitting stage side as a local madam (Pete Herman’s ex-wife, Norma Wallace) and one of her girls “were caterwaulin’, biting and hitting.” That’s when the madam knocked the sex worker on her back, grinding her heel in her face as Hyp rooted her on. (Bill Grady, Times Picayune, October 23, 1994)

Meanwhile, the young Assunto brothers had both married. Playing music was a serious profession that they depended on to support their new families. They also knew that their ticket to fame did not include sharing Hyp’s bill with a bald stripper – his latest discovery.

Frank and Joan Assunto’s wedding, 1954, with Permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

Freddie and Betty Assunto’s wedding, 1955, with permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

“There are two kinds of music: the good & the bad. I play the good kind.”

-Louis Armstrong

In 1955, the Assuntos moved to Las Vegas. From there, they could tour half the year and headline at the casinos the rest of the time. The brothers lived around the corner from each other. Before long, Jacinto and “MaMa Jo” (Josephine Messina Assunto) also relocated from New Orleans.

The year before, “The King of Swing,” Louis Prima – with Sam Butera and The Witnesses – had taken Las Vegas by storm, and the band established “residency” at the Sahara. Prima and his manager, Joe Segreto, were catalysts, establishing a New Orleans’ Sicilian outpost in Nevada. Sam Saia regularly shipped crawfish from Felix’s to keep the Louisiana natives well fed in the desert.

Betty and Fred Assunto’s house became a home away from home for both Al Hirt and Pete Fountain when either musician was performing in Vegas. Betty’s red beans were legendary. Phil Harris was so impressed by “the Duchess’” cooking that he called his wife, Alice Faye, long distance. Harris yelled into the phone, “Alice, can ya smell ‘em?”

The family aspect of their act only added to their popularity. Their father received a standing ovation each time he joined his sons on Vegas stages. “MaMa Jo” was not only a doting Nonna – she was also the band’s bookkeeper.

Frankie stayed focused on keeping the Duke’s music vibrant – and the income coming in to support the family. In their off time, Freddie and his father shared a passion for photography.

In a November 1957 release, the Dukes of Dixieland became the first jazz band in the world to be recorded in stereo. Sidney Frey of Audio Fidelity Records put the Dukes’ music on one side and train sounds on the other to show off stereo’s acoustic range. It would be 12 years before the Beatles would record Abbey Road in stereo. Photograph © Jacinto Assunto, with permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

In 1958, at a dinner at New York’s Friars Club, Frey surprised the Dukes with a check for $100,000 advance against royalties., with permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive

Armstrong cutting up with the Dukes in the recording studio, 1960. Click here to read more about the recording from Armstrong scholar Ricky Riccradi. Photograph © Jacinto Assunto, with permission of Deano Assunto/The Frank J. Assunto Dukes of Dixieland Archive.

“I tell a new guy in the band. ‘Look, man, I hired you to play your horn. You figure out what the heck to play on there. You know, this is a jazz band, it’s not a prison. So have a ball. Play good. That’s all.’ If you don’t have fun, the audience is the first to know it. And if you don’t have fun, how can you play?”

-Frank Assunto. Interview with Bob Byler, jazz scholar and chair of journalism at the University of Evanston, 1967

“The Ed Sullivan Show” dominated America’s living rooms on Sunday nights on CBS from 1948 to 1971. In 1953, Sullivan told his audience that he’d been taken to the Famous Door to meet the Assunto Brothers.

In 1958, he introduced them as “America’s number one combo.” The act was such a hit, Sullivan had them back three times that year.

On January 7, 1959, Louis Armstrong and the Dukes shared the stage in New York on The Timex Jazz Hour, broadcasting New Orleans down-home jazz into living rooms across America. A few months later, on April 10, 1959, the Dukes sold out Carnegie Hall. The concert was released as “Carnegie Hall Concert, Vol.10.”

Louis Armstrong with the Assuntos’ children, photograph © Jacinto Assunto, Frank, jr. became a rock and roll musician with the band Force of Habit, winner of the New Orleans Jazz Fest Talent search in 1988 &89. Deano has served as the President of the New Orleans Jazz Club (NOJC) since 2017. His book about father and uncle is slated for publication in 2026.

After Dukes completed their 64-week residency at the Thunderbird, they were invited to perform at the Copa Room at the Sands. In the early 1960s, that was the official playhouse of the Rat Pack – the founding fathers of Las Vegas super-star acts.

Two Italians, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, headlined with the multi-talented Black entertainer, Sammy Davis, Jr. The two brothers from Uptown New Orleans were keeping good company.

The Dukes became the first Dixieland group to sell 1 million albums, to play at Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl. Including their duets with Louis Armstrong, their record sales topped two million.

Yet they faced one enormous challenge. When could Louis Armstrong and the Dukes entertain mixed audiences in the very birthplace of jazz? By 1956, Louis Armstrong – like many other national acts – stated that until Louisiana banished Jim Crow laws, he would never again play a concert there for segregated audiences.

It would be another twelve years before Armstrong could share a bill with the Dukes in their own hometown.

Up next: Daniel Moses Barker: Grand Marshalling Social Change