Mardi Gras 1979: Mambo Moments

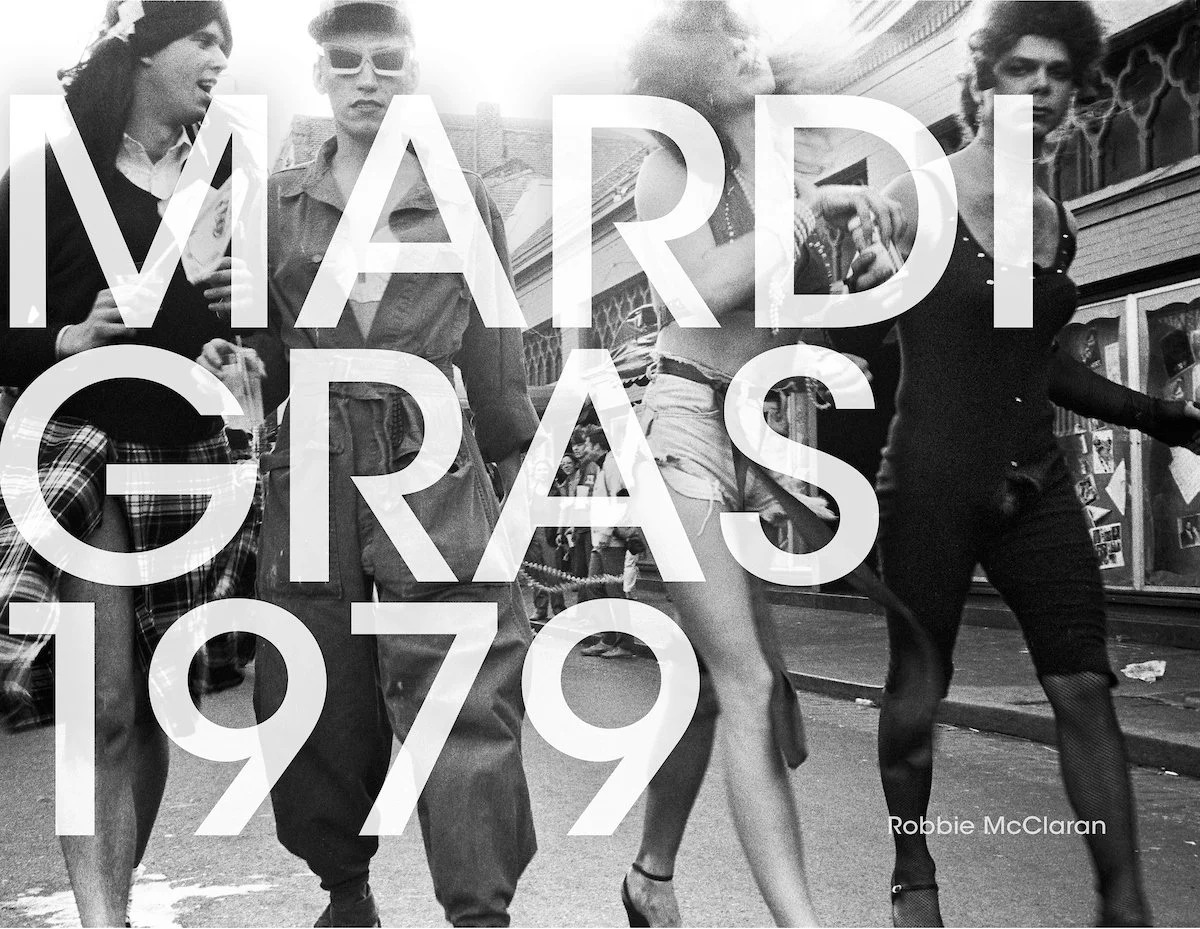

Royal Street, Mardi Gras Day, February 27,1979. Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp Street

February 2026Although Mardi Gras was officially canceled because of a police strike, a young musician experiencing her first Carnival is left with joyous – and unforgettable – memories.

– by Ellis Anderson

– photographs by Robbie McClaran

Robbie McClaran’s photographs used in this piece are protected by copyright, so do not download, and/or reuse in any fashion without prior written permission.This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

When we were still a good half-block away from home, John and I could hear Mardi Gras Mambo blasting out the doors of Shakey Jake’s bar. The beat to the classic song numbed the blisters on my feet and we danced more than walked the rest of the way to the corner. Mardi Gras may have been officially canceled, but locals kept telling me this was the best one ever.

At the intersection, two soldiers in green uniforms faced in the direction of the bar, rifle barrels resting against their shoulders. I had just turned 22 and they looked years younger, like ROTC guys from high school. Thousands of National Guard troops from outside the city had been brought in to pinch-hit for the city’s striking police force. Armed pairs were stationed all over the Quarter, insignificant green islands of authority in a free-running river of jubilation. Most of these Louisiana boys were probably experiencing their first French Quarter Mardi Gras, just like me.

John and I hung back against a wall to watch their reaction to the crowd. Girls in sequined costumes with necklines plunging to their waists tilted their breasts toward the boy soldiers, smiling, inviting. A cluster of passing hippies smoking a joint as they passed blew a cloud of smoke in the direction of the guards, trying to share the high.

Mardi Gras Day, February 27,1979. Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp Street

The soldiers maintained straight faces, like they’d taken lessons from the Queen’s guards at Buckingham Palace. When a man in a clown’s costume offered them two plastic cups of beer he bought for them in Jake’s, they ignored him. He set the beers by their boots as a tribute.

More Harleys than usual were parked in front of Shakey Jake’s [now the Gold Mine]. The motorcycles looked strangely vulnerable as the throngs swirled past them, but they were protected by an invisible force field: the most insensible drunk’s survival system somehow cautioned against the terrible retribution that awaited any unfortunate who stumbled into one of the bikes.

Above the bar, a dozen or so people leaned from the balcony. They hooted and waved to catch the attention of passersby below, rewarding those who looked up by tossing a strand of shiny beads. The balcony our apartment shared with others still didn’t seem crowded because it wrapped the corner building and had no dividers. People could spread out. I recognized a few neighbors, Chuck, Michael. The rest were strangers.

Balconies all through the Quarter, like the ones of this hotel, were packed during the “canceled” Mardi Gras Day,= February 27,1979. Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp St.

While many iron gates in the Quarter were postcard-worthy, the one leading to our apartment above Jake’s looked exactly like the door to a jail cell. It led into dingy alleyway where an open drain ran along one side. It must have been the outlet from a drain behind the bar. Most of the time, the fetid liquid in it reeked of stale beer, but in the mornings when they poured the mop water down the drain, it was cloudy and stank like disinfectant.

This day, it ran like a swollen river of slime. One misstep and you’d have to throw away your shoes. No one who lived above the bar complained, especially musicians like us. We understood it as the main reason for our cheap rent – that, and the music from the biker bar that never closed. Some mornings the vibrations of the bass shook the bed enough to wake us up.

Once through the gauntlet and up the stairs, things improved considerably. The five apartments on the second floor had been recently renovated. Like the others, the three rooms of our shotgun apartment had been left with the original fireplace mantles and twelve-foot ceilings. That alone made it seem palatial to someone who’d grown up in a North Carolina tract house where a kid could knock herself out on the low ceilings just by jumping on the bed.

In our apartment’s front room, two floor-to-ceiling windows opened onto the balcony. The windows were so big, even though I was tall, I barely had to duck when the bottom sash was open. John and I grabbed a snack from the fridge, then stepped onto the balcony and back into the cacophony. While I needed a break from the swirling slurry of the streets, I also couldn’t bear the thought that I might be missing something.

Since we lived just a block from the commercial part of Bourbon Street, the energy at our intersection sizzled. The balcony provided a perfect observation post, we could engage, yet pee at will and leave our shoes off for a while. Not that we had finished roaming the Quarter yet – no way.

***

Bourbon Street, Mardi Gras Day, February 27,1979. Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp Street

Many locals old enough may still grant 1979 the People’s Choice Award as the best Mardi Gras ever – maybe because it was the party that wasn’t supposed to happen. Tourists were warned to leave or stay in their hotel rooms. Officials predicted riots and flames in the streets. Chaotic forces of evil would surely detonate the town as soon as the police pulled out.

Instead, it turned out that everybody just wanted to have a good time. Once the pressure cooker lid of authority was yanked off the city, the steam that rose up was infused with good-will and merriment. Civil disobedience was lifted into the realm of art that day.

***

Mardi Gras Day, February 27,1979. Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp Street

Looking down from the corner of the balcony, the soldiers stood almost directly below us. The beers the clown had brought them had vanished. Had they been kicked over? The pavement was covered with a blanket of go cups and broken beads.

Then John beckoned me over to him, pointing up Dauphine Street. A marching krewe of some sort snaked in our direction, still more than a block away. I struggled to make sense of what I was seeing. Exposed flesh and black leather made the first impression. Male muscles, boots and hats, silver studs, bull whips snapping overhead. Perhaps a dozen men made up the S&M-themed crew. Disco music blared as they moved forward, one of them shouldering a boom box. Heralds blowing shiny trumpets cleared the way in front, making way for the king of the krewe and his dukes. Knights in leather chaps with bare buttocks gyrated on all sides of the inner court.

I remember the regent as a large man, crowned and richly clad in a black velvet cape. In one hand, he held a gold scepter shaped like a phallus. In the other, the handles of two long chain leashes. Each chain ran to the wide leather collar of a nearly naked man, painted head to toe in gold. The youths wore leather shackles on their wrists and ankles. Their only clothing was a small patch of fabric covering their genitals, held in place by rawhide thongs. Like runway models, they displayed their shimmering limbs and torsos and asses to the stunned-stopped gawkers on the sidewalk, proud of their role in the spectacle.

As the group proceeded beneath us, the music and shouts of the crowd made a cacophony that would have drowned out anything I would have said to John, but I made my mouth into a wide “O” of surprise and widened my eyes. He laughed at my reaction. Watch, watch, he mimed, pointing to the soldiers.

The faces of the guardsmen struggled to remain stern, but their eyes opened even wider than mine. As the king reached the point where he stood directly before them, he blew a silver whistle, piercing the air. The phalanx stopped instantly and turned toward him, dancing in place to the disco beat.

The king tapped the golden man on his right with the phallic scepter. He obediently came and faced the royal, then dropped to his knees. The king whipped back his cape, revealing himself. The golden man began ministrations.

It didn’t take long. The king threw his head back and howled, the horns blew, the krewe roared. Some of the spectators cheered. Others, like me, were too stunned to process what we’d seen. The golden man wiped his lips primly, stood and took his place back in the procession. The heralds blasted their horns and the crew resumed its march toward Canal Street.

I was trying to read the expression on the soldiers’ faces when the reveler in the clown suit reappeared. He held two fresh beers in plastic glasses.

This time, the soldiers accepted them and drank deeply.

Photo© Robbie McClaran, from his book, Mardi Gras 1979, used with his permission. Original prints are available at Martine Chiasson Gallery, 727 Camp Street