Quarter Rats

WIlliam Woodward painting of Napoleon House, 1904, which includes the tobacco shop of the writer’s great-grandfather, Auguste Glaudot, Jr.. Print image courtesy James Nolan

July 2025A writer with deep generational ties to the French Quarter takes readers back in time, then guides them through a century of change.

– by James Nolan

Excerpt from the prologue to French Quarter Fiction: The Newest Stories of America’s Oldest Bohemia (Light of New Orleans Publishing)This column is underwritten in part by Karen Hinton & Howard Glaser

I come from a long line of Quarter rats. We inhabit crumbling buildings, seldom poke our snouts out of the French Quarter, and like our distant cousins the cockroaches, can stay up all night and will eat anything.

Of the five generations of my family in New Orleans, only my mother has never lived here, but her first job was as a secretary in a dress factory located three blocks from my apartment. As a child, when I'd present her with some loopy drawing, she'd exclaim, "Why, that's so good you could take it to Jackson Square."

That was her ambition for me, to become a painter on Jackson Square, but perverse as ever, I became a writer instead. You see, everything and everyone in this neighborhood has a story: art, buildings, bars, restaurants, shops, rats, even writers and their mothers.

A favorite daydream of mine takes place at my great-grandfather's tobacco shop, at the corner of St. Louis and Chartres. It's 1893, let's say, the year my grandmother was born, when the family moved from their apartment above the shop to the courtyard maisonette on Royal Street.

Auguste Glaudot, Jr.’s cigar store on the corner of Chartres and St. Louis, circa 1900, courtesy James Nolan

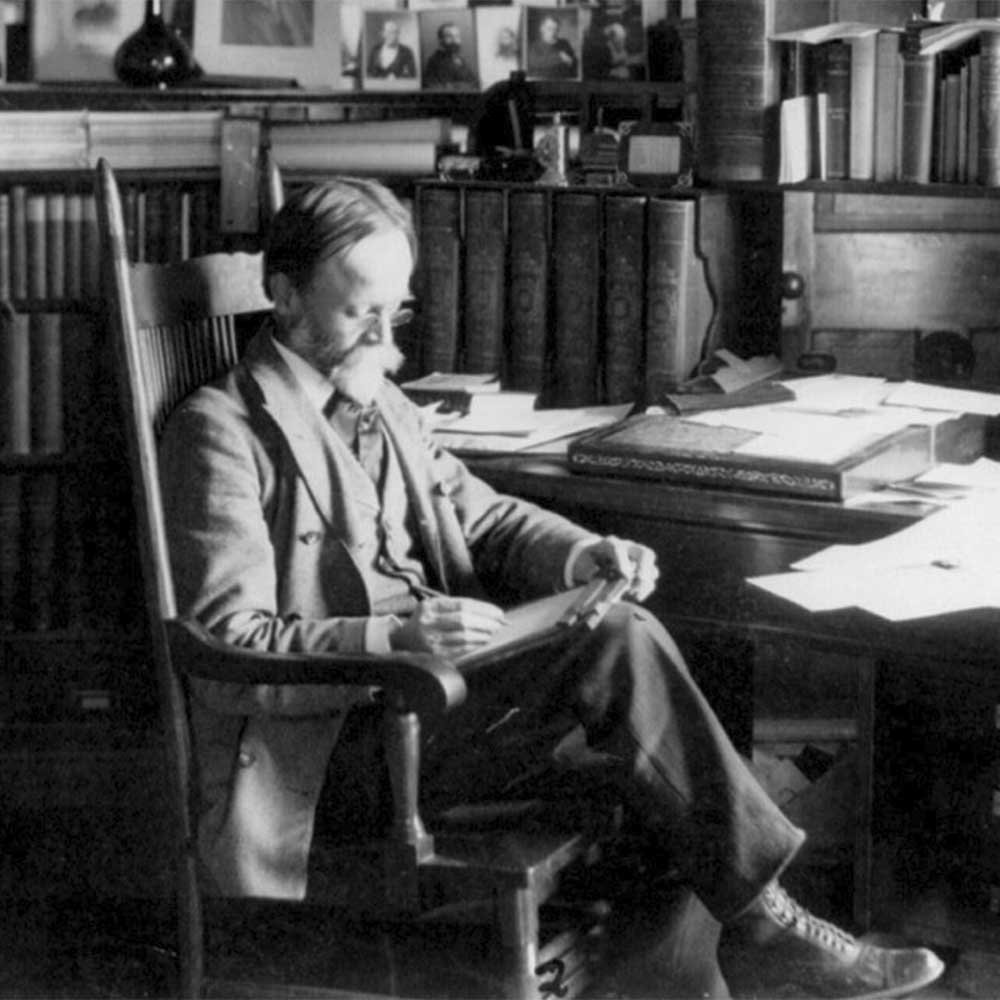

Auguste Glaudot, Jr., at Chartres St. tobacco store, photo courtesy James Nolan

My great-grandfather, Auguste Glaudot, has been home for three years after his sojourn in Belgium and France to visit relatives. He is speaking French with a dwarfish Quarter rat in a wide round hat that makes him look like an ambulant mushroom. Lafcadio Hearn switches into English to welcome George Washington Cable. Back from a lecture tour with Mark Twain, Cable has stopped in for a cigar. My great-grandfather abruptly turns his shoulder. Cable slandered the Creoles in The Grandissimes, and nobody speaks to him anymore.

An imposing woman in a red tignon passes the shop, carrying a basket of roots. Is that the Widow Paris from rue St. Ann, they whisper, or her daughter Marie Glapion, also known as Marie Laveau? The light-skinned voodooienne is walking with an ancient African wearing a gris-gris necklace, Jean Montanet, a.k.a. Dr. John from Bayou Road. Both Hearn and Cable have written about Dr. John, so they rush outside to greet him.

Then up walks Père Roquette, a parish priest from the Ursulines convent who dresses like a wild Indian. He's known as Chahta-Ima among the Choctaws in St. Tammany Parish. Hearn quizzes the priest about the interview he gave in The New Orleans Bulletin, done by someone called Walt Whitman.

"That name," Hearn says, "rings a bell."

Lacadio Hearn in 1889, photo Wikipedia Commons

George Washington Cable, 1898, Library of Congress

The writer’s great-great grandfather Auguste Glaudot Sr., 1830 Brussels-1908 New Orleans. He established the tobacco business.

Then my great-grandmother walks by her husband’s tobacco shop carrying her newborn, Olga, and from her mother’s arms, my grandmother is staring up wide-eyed at the characters standing on the corner.

Then suddenly it’s 1963—seventy-three years later—and, already an old lady, Mémère is sitting with her sixteen-year-old grandson at the kitchen table, reminiscing about her old neighborhood. Why should she care if Jimmy goes to the French Quarter? They say it's wild and bohemian down there, but what are guitars and longhair to her, after the world she grew up in?

"Now you get home early,” Mémère says.

But, of course, I never did.

The writer’s grandmother, Olga Glaudot Partee, with the writer’s mother, newborn Helen Alice, French Quarter, 1924. Photo courtesy James Nolan

As the busiest port in the country, New Orleans reached its zenith of wealth and power in the 1840s. And it's been downhill ever since.

A decadent port is the perfect place to foment a literary bohemia, providing the three essentials: creative misfits, cheap rent, and a window onto the world. The French Quarter has possessed that magic combination of ingredients during several distinct eras. The first were the neighborhood eccentrics that I often fantasize visited the family cigar store. Local colorists such as Cable, Hearn, and Kate Chopin wrote vivid portraits of the Creole neighborhood, a previously unmapped enclave of French Caribbean culture entrenched north of the Canal Street "neutral ground," at war with the money-mad Americans on the other side.

The Americans won.

And by the First World War, the Creoles were in retreat, and most had abandoned the Quarter for Esplanade Avenue. Their shops and homes had fallen into disrepair, and were taken over by Sicilian immigrants who set up groceries on almost every corner.

The French Market, 1920 - 1926, by Arnold Genthe, Library of Congress

Decatur Street, between Dumaine and St. Philip, 1935. Photography by Walker Evans, Library of Congress

This was the slum that William Faulkner discovered in 1924, when he rented an apartment in Pirate's Alley and described the Quarter as "this courtesan, not old yet no longer young." Sherwood Anderson, already ensconced in the Pontabla Building, had put out a call to young writers to come to the "most civilized place I've found in America."

And they did come. Faulkner, Anderson, John Dos Passos, and Anita Loos met up with locals such as Lyle Saxon and William Spratling to form a bohemia often described as Greenwich Village South. They came for the ambience, each other's inspiration, and—make no mistake about it—the booze that kept flowing during Prohibition. In no way were the Puritan restrictions of Anglo-America enforced in an Italian neighborhood with Spanish architecture, French culture, and African street life. The Quarter then was one big speakeasy.

By the beginning of the Depression, most of these writers had scattered, as the local colorists had by the turn of the century. Who remained in the Quarter were artists applying the folkloric concept of local color to painting, a bold breakthrough at the time. Their realistic canvasses of Louisiana life, of its swamps, plantations, and street scenes appealed to visitors, so they began to take their work to sell in Jackson Square. This was the era that fostered such a great photographer as Clarence John Laughlin, although the regional esthetic later degenerated into much of the souvenir shop merchandise sold today to tourists.

Curiously, most American bohemias have taken root in immigrant Italian neighborhoods—Greenwich Village, North Beach—and this was also true of the French Quarter. Quarter-rat painters became honorary Mediterraneans, donning berets, downing espressos and dago red, and scraping by on pasta in tenement rentals.

French Quarter courtyard between 1920 - 1926. Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

For a long while these painters formed the backbone of Quarter bohemia. They could both live here and make their living "on the fence," as they called Jackson Square. When Tennessee Williams arrived in the French Quarter in 1938, he carried a letter of introduction to two such painters, Knute Heldner and his wife, Colette Pope.

Williams' Quarter of the forties was a brawling seaport filled with foreign sailors, pimps, hookers, burlesque clubs, and the first gay bars. During his stay, William Burroughs—"author of Junkie and Queer," as a marker proudly proclaims in front of his former house in Algiers—no doubt found everything he needed right here. This was when the neighborhood acquired its enduring reputation for vice, the Quarter of my parents' generation.

My father warned me in high school about "getting rolled" down here, afraid someone would "slip a Mickey" in my drink. My grandmother may have fancied I was going to the Quarter to mourn the French Opera House of her youth, just as my father figured I was heading to the Hotsy Totsy Club of his, but neither was the world I was searching for.

Gypsy Lou Webb with Charles Bukowski, gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Where I was going were the integrated coffeehouses and blues clubs, not to mention the uproarious Discussion Group. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Quarter was part of what was called the Golden Triangle, encompassing Greenwich Village and North Beach, for everyone "on the road."

The local scene was energized by the Civil Rights movement and the arrivals of Beat writers and jazz musicians from New York and San Francisco. Folksingers wailed Odetta from coffeehouses, demonstrations were plotted, and jazz-and-poetry collaborations filled the air. Small literary magazines such as John and Gypsy Lou Webb's The Outsider included work by Charles Bukowski and also a poet who was later to become my friend and publisher, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, both of whom were often in town. A young native named John Kennedy Toole was taking this all in, and certain sources swear that miscreants were conspiring inside courtyards to assassinate another Kennedy, the President.

Then the Quarter was still home to a working port, and seedy bars such as La Casa de los Marinos and the Acropolis on Decatur Street blared Latino and Greek music that lured both foreign sailors and local bons vivants. Drinking in those dives formed my first contact with the world at large, and inspired my lifelong wanderlust.

La Casa De Los Marinos, 1960s, Wikimedia Commons

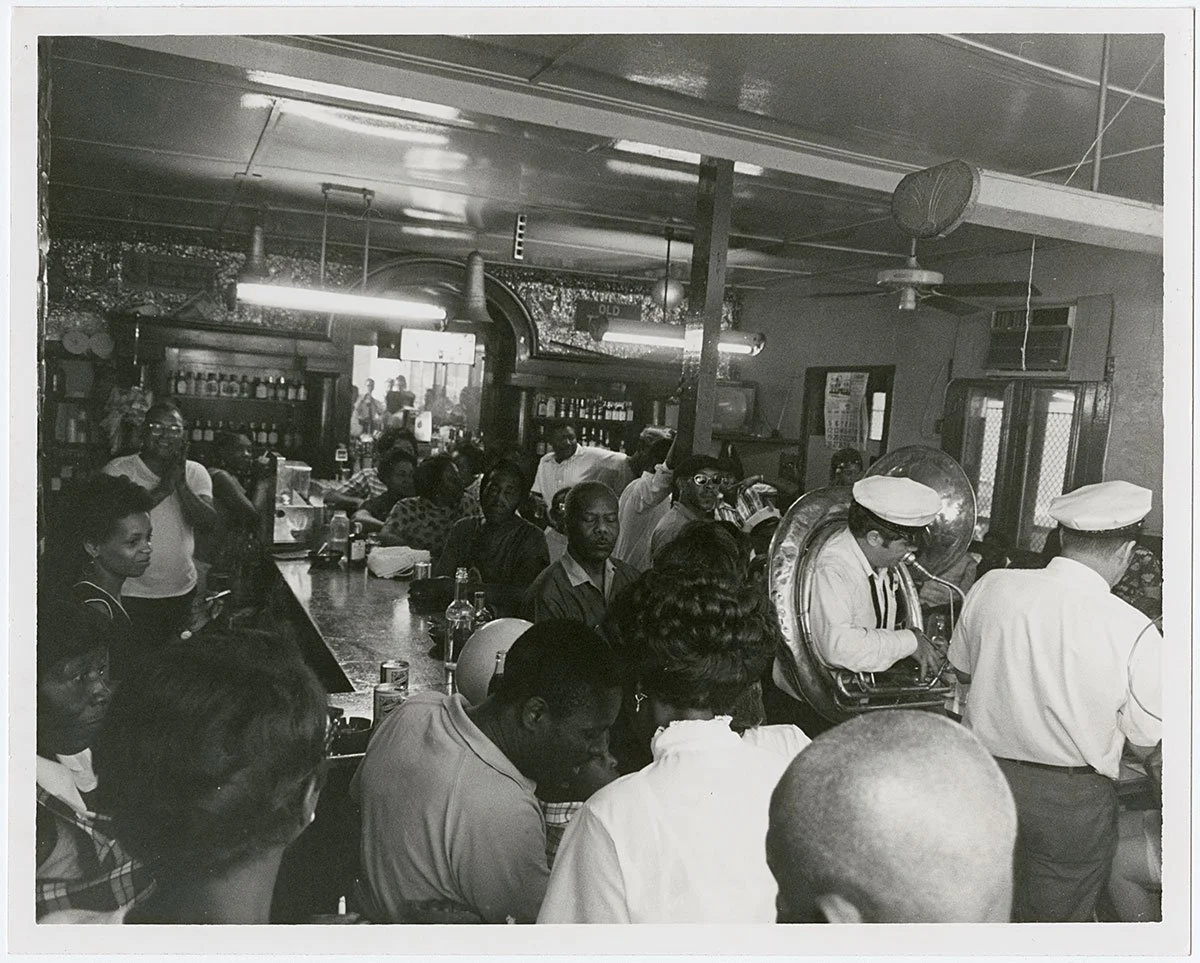

In the coffeehouses, skinny women with long ironed hair stirred their cafés au lait while “outside agitators” railed on makeshift stages against segregation. A plate of red beans and rice—with sausage—cost thirty-five cents at Buster Holmes Restaurant on Burgundy Street, and all of the painters on the Square had passed out in each others’ beds at least once.

Interior of Buster Holmes, 1970, by Jules Cahn, courtesy Jules Cahn Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection, 2000.78.1.1677

This was during the reign of Ivan and his Discussion Group.

Ivan’s “disgusting group,” as it was sometimes called, met every other Friday night during the fifties at his apartment on Bourbon Street, and continued for more than twenty-five years at various locations in the Quarter. Still a high-school student in the mid-sixties, I usually arrived late and sat quietly on the floor in a corner while someone was ranting about a brutal encounter with the cops or about that French fat-ass, Sartre. The glasses were greasy and the jug wine cheap.

The discussions inevitably turned into knock-down, drag-out fights between Ivan, a walrus-mustachioed painter on the Square, and Helen, a retired vaudeville star from New York. Everybody else chimed in, took sides, got drunk, found a place to stay, picked each other up, borrowed money, and, as was often the case, had Blakean revelations at three in the morning to take off in rattletrap cars for New York or San Francisco.

Everybody went: painters, poets, integrationists, street musicians, itinerant magicians, college drop-outs, rough trade, Uptown debutantes just out of the loony bin, and whoever you happened to be talking with the night before in the third bar of La Casa. These people weren’t quite beatniks and not yet hippies; the community was inclusive rather than exclusive. There was no hipster costume or creed other than tolerance, creativity, and an ongoing lover’s quarrel with poverty.

After World War II, when the country clamped down with a vengeance to normalcy, this ragtag group of rebels—largely the misfits from every town below the Mason-Dixon line—came together as a way out of the small-mindedness of the segregated South of the Eisenhower years, and in the process helped the fifties turn into the sixties.

Arists along the fence in Jackson Square, 1960s, Courtesy HNOC, 1974.25.14.34. Read more our archived story: On the Origin of Jackson Square Artists: “They were a Rowdy Bunch”

There I first met Black people socially, as well as independent women, gays, street artists, political activists, people over thirty who didn’t act like my parents, and other kids like me who were running away from home without yet leaving town. This was where I encountered the older friends who later would serve as my introduction to the adult world, including the Satanist poet John Foret, the writer Ben Jennings, the artist John Kamas, and the troubadour Jerry Jeff Walker, as well as the Jaffes and Borensteins, who started Preservation Hall.

You wouldn’t have read about these bohemians in the culture section of The Times-Picayune, although occasionally their names did pop up in the crime section, such as when the police raided the Quorum Coffeehouse on Esplanade, which was conducting Black voter-registration drives. Those arrested were cited for—the words still reverberate through the decades—“the tuneless strumming of guitars and pointless intellectual conversation.”

At the time, the blues musician Babe Stovall was standing under balconies reminding us with twelve steel strings played on the guitar behind his back that “there trouble in this land, God gonna move his hand and time is winding up.” And after not too long, time did wind up, in ways that few of us then could have imagined.

By the late seventies, this bohemian enclave had dispersed, as did those before it. When the gigantic modern freighters no longer fit inside the wharves, the port was moved upriver and the Quarter lost its connection to the vital grit of marine commerce. The legitimate businesses and shadowy demimondes that fed off the port also vanished from the neighborhood. Fortunately, during the sixties, preservationists quashed plans to erect an elevated freeway over the Quarter and to install a sound-and-light show in Jackson Square.

The protest against Sound and Light, July 19, 1975. In the foreground is the poster designed by artist Steven Max Singer. Photo by Robin Von Breton. Read our archived story: The Sound and Fury over “Sound and Light”

But the 1984 World's Fair ushered in the final stages of waterfront redevelopment, and the decaying port was converted into a theme park. The truth is, the Quarter isn't wicked anymore but just pretends to be, and now makes its living off of conventioneers so drunk they can't tell the difference.

It’s as if Faulkner's aging courtesan had closed the shutters, taken a long look in her vanity mirror and decided honey, it's time to live off your reputation.

Yet like Tangier, the French Quarter feeds on the flesh of its strangers and never grows old.

And after a few years of hurricanes, torrential rains, and steaming summers, even the snazziest renovations will soon look like one of Clarence John Laughlin's phantasmal ruins. But don't be fooled. These few blocks of moldering buildings aren't the French Quarter.

Chartres Street, 2023, by Ellis Anderson

Thanks to the writers and artists who have passed through here, the eternal Quarter exists as a place in the imagination that imbues these worn bricks and rotting boards with magic. Only occasionally, and at unexpected moments, can you catch bewitching glimpses of the real Quarter.

Lafcadio Hearn, one of the first Quarter rats, got it right long ago when he compared the neighborhood to "one of those phantom cities of Spanish America, swallowed up centuries ago by earthquakes, but reappearing at long intervals to deluded travelers."

James Nolan’s most recent book is Between Dying and Not Dying, I Chose the Guitar: The Pandemic Years in New Orleans (UL Press). Flight Risk: Memoirs of a New Orleans Bad Boy (University Press of Mississippi) won the 2018 Next-Generation Indie Book Award for Best Memoir. His prize-winning fiction includes You Don’t Know Me: New and Selected Stories, the novel Higher Ground, and Perpetual Care: Stories.

His latest book of poetry is Nasty Water: Collected New Orleans Poems, and other collections include Why I Live in the Forest,What Moves Is Not the Wind, and Drunk on Salt. His translations from the Spanish are Neruda’s Stones of the Sky as well as the just released If Only for a Moment (I’ll Never Be Young Again): Selected Poems of Jaime Gil de Biedma. He has received an N.E.A., Javits, and two Fulbright fellowships, and taught at universities in San Francisco, Barcelona, Madrid, Beijing, and Florida, as well as at Tulane and Loyola in New Orleans, where he now lives. Contact him at jnolan77@bellsouth.net. Website: www.pw.org/directory/writers/james_nola