Philip M. Core: Torchbearer for Artistic Freedom

“The Demidoff Vase” by Philip Core, from the book Philip Core Paintings, 1975 - 1985. With permission of the Philip Core estate.

May 2025Only nine years old when he won a prestigious French Quarter arts competition, New Orleans artist Philip Core used that innate talent to blaze trails for the freedom of artistic expression – across two continents.

by Bethany Ewald Bultman

This Sketchbook column is underwritten in part by Betsy Fifield

In 1960, at a time when watching cartoons was the chief entertainment for many New Orleans children, nine-year-old Philip Core became captivated by the work of a ground-breaking 19th-century English illustrator.

Since there was no age requirement for a Vieux Carré artists’ invitational, the boy submitted an Aubrey Beardsley-inspired rendering to be judged alongside many of Jackson Square's seasoned professional artists.

Core’s work won first place.

By the 1980s, Core was telling the story to entertain dinner companions as the artist gained prominence as one of London’s creative trendsetters – and a trailblazer for freedom of expression.

Core’s final act of defiance before his untimely death in 1989 was to mail a package from his mother’s Uptown New Orleans home to his studio in South London. It contained a book by homoerotic artist Tom of Finland and photographs Core had taken as studies for paintings.

It was 1988. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s promise to free the British Isles of the alleged homosexual threat resulted in Core’s package being confiscated. Normally, it would have been burned. But Core, refusing to be cowed, challenged the law in court – just days before his death.

“If I got rid of my demons, I’d lose my angels.”

Tennessee Williams - Playboy 1973

As a toddler in Madras, India (modern-day Chennai), Philip Core, who’d been born in Dallas, Texas, spoke Tamil before he learned English. He would not have survived his attraction to a hissing cobra had it not been for his vigilant ayah and a spade-welding gardener. While Core didn’t remember the specifics of this episode as an adult, in later interviews, he used the anecdote to illustrate his fascination with the dueling elements of innocence and menace.

In “Consular Families,” Core pays homage to the Ayah who protected him as his parents entertain in the background. The painting was first exhibited in a one-man show in 1979 in “Pieces of Conversation” at London’s Francis Kyle Gallery. From the book Philip Core: Paintings 1975-1985, GMP Publishers, Ltd. 1985. With permission from the Philip Core Estate.

After his father, Jesse Rozell Core, III, completed his four-year stint with the U.S. Foreign Service, Philip’s parents settled in New Orleans, a port city some considered to be more Euro-Carribean than American. His mother, Lucy Ruggles Core, was the daughter of the esteemed editor of the Dallas Morning News, Bill Ruggles.

Lucy secured a post as an editor at a small press at the epicenter of the city’s “Dixie Bohemia,” while Jesse wrote two novels and worked in public relations for D.A. Jim Garrison – and for Clay Shaw – at the International Trade Mart.

“One Mardi Gras night Philip and I were allowed to spend the night on a Pontalba balcony as our parents decided to stay in the French Quarter.” Marguerite recalled. “We stayed up until the wee hours of Ash Wednesday watching the bats majestically circle the St. Louis Cathedral belfry. Photograph by Hedrich-Blessing, 1950s, courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection. Acc. No. 1959.198.

In a recent interview with FQJ, Philip’s younger sister Marguerite Core described their sibling bond as that of “a guerrilla unit” within their family. Every Sunday after attending services at Christ Church Episcopal Cathedral, the family would drive to the French Quarter. Beignets and café au lait at Café du Monde were followed by a visit to friends who lived in the historic Pontalba apartments flanking Jackson Square.

His early schooling was at École Classique, where Philip acquired a proficiency in Greek and Latin. As Marguerite Core explained, “visiting the Delgado Museum of Art [now the New Orleans Museum of Art] took Philip hours as he studied every artifact and painting, read every description – and passed judgment on the merits of each.”

His fascination with Aubrey Beardsley informed his early style. It was Philip Core’s juvenile pen and inks, a la Beardsley, that garnered him that first acclaim as an artist.

At that point, his father – an Arkansas-born, decorated WWII fighter pilot and lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve – declared his first-born would benefit from a disciplined military education at the New Orleans Academy (Carondelet and Constantinople, closed in 1986) to drill “all that artiness” out of the boy, according to Marguerite.

Esprit de Core

In 1963, thanks to a scholarship, the precocious twelve-year-old was dispatched to the prestigious Middlesex Preparatory School in Concord, Massachusetts. Left to his own devices, his artistic aspirations flourished. Core founded Middlesex’s literary magazine, Icon; became a theater critic for the Concord Free Press; produced several short films and self-published Palm Fronde Alphabet, a book of his drawings.

Philip, aged fifteen, in the Dallas garage of Jaunita “Cookie” and Alfred Bromberg (in what is called the Bromberg-Patterson house now), creating large cut-outs for the family’s Fourth of July bash. Circa 1966, from the collection of Marguerite Core.

By November 1966, the fifteen-year-old Core was in demand for his fashion designs at Betsey Johnson’s trendy Paraphernalia Boutique in New York. His sister, Marguerite, proudly modeled a trendy paper dress Philip brought her. From the collection of Marguerite Core

The Core siblings in the summer of 1967: the middle child, Marguerite (12), Philip (15) and Mason (9) with their parents on a visit to Dallas. The family station wagon behind them, with its roof packed and protected by a tarp. From the collection of Marguerite Core

The teen spent his Christmas and summer school vacations in New Orleans. Philip Core later acknowledged many of his artistic enthusiasms were projected against New Orleans’ neo-classical backdrop, filtered through Poe’s stories and overshadowed by Greek statuary.

His eye was trained to capture decadent contradictions: majestic 19th-century homes lined streets vulnerable to the will of the mighty Mississippi, with pristine paint jobs on their faces and decay on their unpainted sides.

Philip Core was also an unashamed homosexual teen with an itch to apply his talents to homoerotic art. In 1962, the United States Supreme Court ruled that male nude photographs were not obscene (MANual Enterprises v. Day). Beefcake “fitness” magazines were the first to test the limits of laws against pornographic images.

In 1967, under the pseudonym Féllippé Fecit, the sixteen-year-old Core produced a series of erotic drawings to illustrate the Canadian poet John Glassco’s poem about flagellation, “Squire Hardman.”

“The Haunted Ballroom,” first exhibited in “Novels without Words,” a one-man show in 1980 at London’s Francis Kyle Gallery. Inspired by the artist’s New Orleans childhood, well lubricated subjects languish as if collapsing under the pressure of trying catch a breeze amidst a profusion of artistic metaphors and dearly departed celebrities. The city’s above-ground tombs loom outside. From the book Philip Core: Paintings 1975-1985, GMP Publishers, Ltd. 1985. With Permission from the Philip Core Estate.

Philip Core in the spring of 1969 at his Middlesex graduation, smoking his ever-present Marlboro. From the collection of Marguerite Core.

Photo of bearded 18-year-old Philip. Core firmly stated in a cadence more suited to the 19th century than the swinging ‘60s, “I want to see if I can stay happy when I get famous. I think that one should set one’s own standards as long as one follows gentlemanly traits.” At the end of the teen’s interview, Ball observed “Philip pulled at his beard and smiled. ‘I know I sound pompous, but really, I do realize that I’m still an unfinished product.’” From the collection of Marguerite Core.

Two years later, in September 1969, The New Orleans Times Picayune profiled Philip Core in its “Terrific Teens” column under the headline, “Writer, Illustrator, Designer Driving Toward Goal: Fame.”

The reporter, Mildred Porteous Ball, astutely observed: “He says he’s eighteen years old, but it’s hard to believe that the Edwardian-looking young man isn’t a great deal older, for Philip Core has definitely been around.”

Core concluded his interview by regaling the reporter with a tale of how he’d spent his summer earlier that year. He and a pal rented a basement apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his roommate threw a party.

The first guests to arrive were ballet icons Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. The next day the dancers invited Core to their rehearsal at Boston’s Music Hall. He was mesmerized by watching Swan Lake atop a packing crate from beside the stage. Nureyev then entertained the teen in his dressing room after the June 7th performance. Core spent the next few days as the dancers’ Boston tour guide.

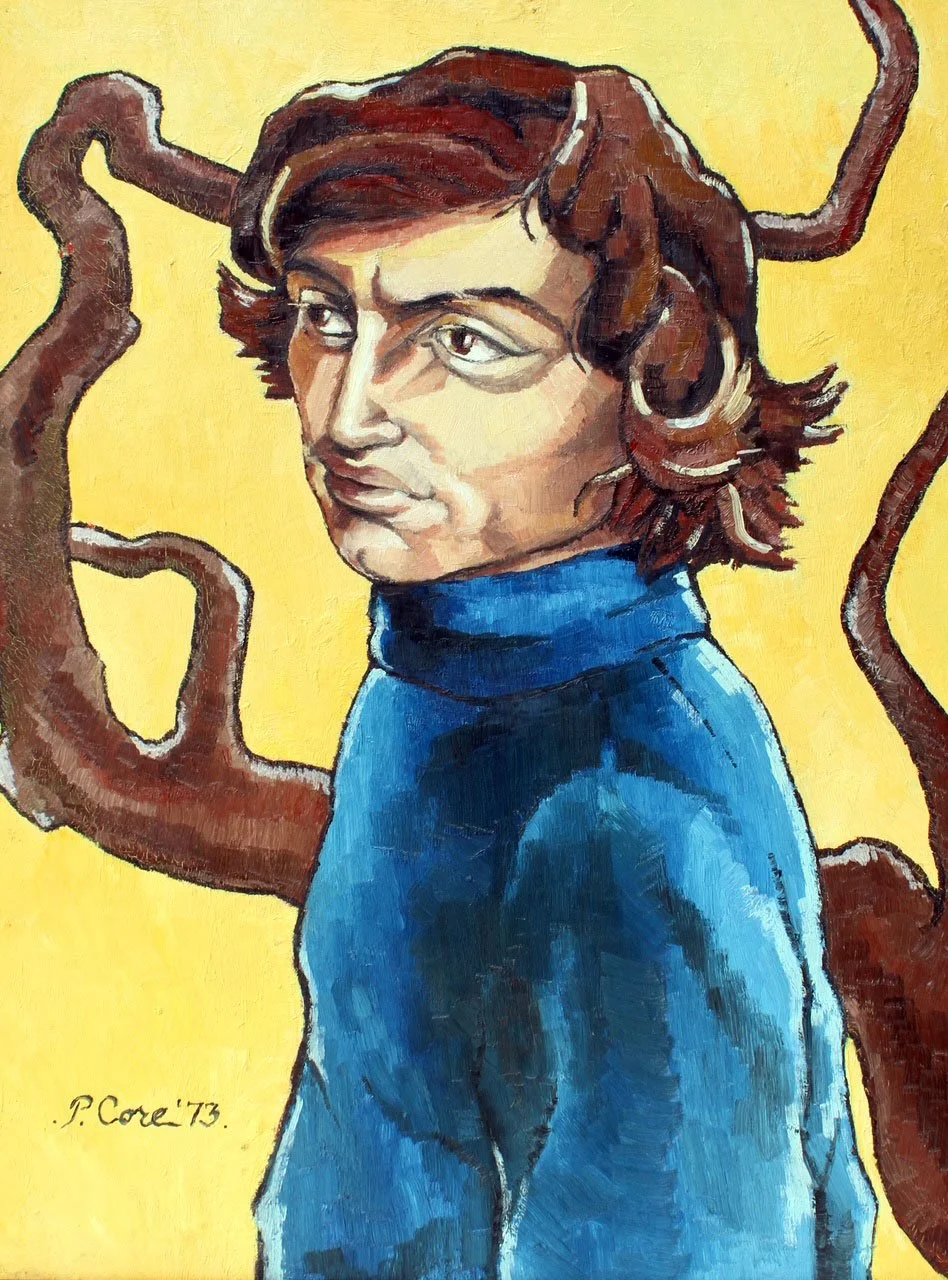

Philip Core oil painting of the scowling Rudolph Nureyev, 1973. Watching Nureyev dance “changed my life,” Core stated (posthumous obituary published in The Independent in 1993). Galvanized by the dancer’s magnificent ability to encompass emotions in one pure sweep of movement influenced how Core painted the male form. To him, Rudolf Nureyev flawlessly personified CP Cavafy's phrase, 'The lips and the skin remember like the soul.” From the Tom of Finland archive with permission from the Philip Core estate.

A few weeks later (June 24 - 26), Nureyev and Fonteyn performed with the Royal Ballet at the Municipal Auditorium in New Orleans. Philip Core was not back in town, but thanks to his relationship with the dancers, his ballet student younger sister, Marguerite, attended all three performances.

Marguerite was even hosted by the regal Dame Margot Fonteyn for tea at her suite at the Pontchartrain Hotel on St. Charles Avenue. Nureyev popped in to greet “Philip’s little sister.” The legendary ballerina confided to her, “the best dancers are very stupid,” advising Marguerite that she was clearly too intelligent to aspire to a career in dance.

“Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else.”

George Orwell, “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (1949)

“As beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella... Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp,” 1976. While still in boarding school, after producing a portrait of Lou Reed, the lead singer of Andy Warhol’s rock band, The Velvet Underground, Core found himself absorbed into their Factory scene on New York’s East 87th. From the book Philip Core: Paintings 1975-1985, GMP Publishers, Ltd. 1985, with permission from the Philip Core Estate.

Harvard University provided Core with a full scholarship and a coveted spot on the Harvard Lampoon staff – as an incoming freshman. Yet, in 1971 after a few semesters at Harvard, Core took a leave of absence to intern in Paris with illustrator Philippe Jullian on his seminal work on the symbolist painters.

Once back at Harvard in 1972, Core had his first one-man exhibition. The following year, in 1973, Core graduated cum laude with a degree in Art History.

Summing up his formal education (in 1986 in London’s The Independent), Core opined, “Harvard was a particularly difficult temple, and my own personality only precariously fitted to its faiths.”

UpStairs Lounge Arson Attack, painting by Philip Core, 1973. Core was not in New Orleans at the time of the horrific hate crime that killed thirty-two homosexual men, but as an an openly gay man since his teens, the fact it happened in his hometown was devastating. In his painting, he depicted bartender Buddy Rasmussen valiantly leading men up to the roof of 604 Iberville on Sunday, June 24, 1973. They were the only survivors. Read more about the tragedy here. From the Tom of Finland archive with permission from the Philip Core estate.

“The man who can dominate a London dinner-table can dominate the world.”

- Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

Philip Core exploded on the London scene at the cusp of 1975. England was amidst a bleak financial depression. Penniless and alone, Core at 24 years old embodied a sui generis mash-up of Oscar Wilde, Truman Capote, Aubrey Beardsley, Noël Coward and Tennessee Williams – enhanced with unique Mardi Gras virtuosity.

The Daily Telegraph (November 15, 1989) described how Core would “sashay about London in motorcycle boots, a bomber jacket and cropped dyed hair.”

A Fair Deal for Homosexuals invitation. Philip Core created the poster for the National Council for Civil Liberties conference at the National Institute for Social Work on May 17, 1977. Adam Low recalls marveling at Core’s unabashed gayness. As Low described, “This was not as common as people might think in Britain in the late ‘70s. In his art and his writing Core was a trend setter who was not incapacitated by shame about his sexuality.” From the Tom of Finland Foundation archive with permission from the Philip Core estate.

The young artist made an entrance at any gathering armed with the best gossip in London; a seductive, syrupy Southern drawl; courtly manners and stoic work ethic (no doubt forged by his prepubescent military school stint). The only impediment to Philip Core’s rigorous ambition was his utter refusal to compromise.

Not only did Core brim with enthusiasm about his latest projects, but he had the remarkable gift of infecting everyone from lords to cabbies with a desire to share in his pursuits.

Arts documentarian Adam Low encountered Core several years after his arrival in London.

“Philip had acute emotional understanding and dedication to his work that instantly drew me to him,” recalled Low.

In an era of drugs, Core viewed chemical stimulants as an impediment to his boundless creativity. The greatest mystery was when he slept. Seemingly simultaneously, he visited exhibits, plays, ballets, concerts, operas, and movies. Soon, London’s demi-monde couldn’t get enough of the transplanted New Orleanian.

The New Orleans society column (States- Item, December 22, 1977) confided that the London-based painter-writer, Philip MacCammon Core, had just sent his parents a photograph of the mural he’d painted on the ceiling of the Mayfair home of Lady Sophie Cavendish, the daughter of the Duke of Devonshire. His proud parents told the reporter that their son was en route to spend the weekend at Chatsworth House, their family’s 300-room 16th-century seat in the Derbyshire Dales.

Adam Low with Philip Core’s“La Traviata” which he bought from the artist. Core depicts Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé as Violetta in La Traviata (In a 1986 interview, Freddie Mercury said hers was the greatest voice he ever heard). Photo copyright Bruce Ormiston

“I’m afraid of losing my obscurity. Genuineness only thrives in the dark. Like celery.”

-Aldous Huxley

Artistically, the ex-pat artist danced atop the razor’s edge between meticulous draftsmanship and narrative-realism, gushing romanticism and high camp.

“Back then, his work was unfashionably figurative and often homoerotic,” noted Low. “Somehow that made Philip’s work all the more appealing.”

Core held court in his studio above a bait and tackle shop in the backside of a trendy South London neighborhood. He camouflaged any tawdriness of his surroundings under gallons of flat black paint.

Philip Core publicity photos, early 1980s, with permission from the Philip Core estate.

From an early age, the artist had gravitated to the magic hidden in the shadows. To his eclectic circle of friends, journalists and collectors, Philip Core’s studio was a Bohemian Goth backdrop for soaking up his encyclopedic knowledge of literature and art history, liberally doused with salacious historical factoids.

Core’s canvases competed for space on his walls and easels, some massive murals even draped on to the floor. Neo-classical scenes of homo erotica abutted Core’s portraits of British aristocrats and punk musicians. By 1976, Core’s work was regularly featured in one-man shows in prestigious London galleries.

In 1984, The Royal Shakespeare Company commissioned Core to paint Roger Rees as Hamlet. The iconic Welsh actor moved to New York to join the television cast of Cheers 1989-1993 and The West Wing 2000-2005, and narrated several vampire-themed Anne Rice audiobooks. From the Tom of Finland archive with permission from the Philip Core estate.

Philip Core landed himself in London’s artistic mainstream in 1980 when the Ritz Hotel commissioned a mural, The Ideal Party, for its Piccadilly entrance. It depicted the illustrious patrons of the hotel’s first 75 years. In 1982, the Ritz ordered a series of historical portraits of various famed hotel guests. The drawings for the mural are now part of the Victoria and Albert Museum collection.

Amidst the English arts’ renaissance, Maxim’s of Paris commissioned Philip Core to be the featured artist in the Henley Music and Arts Festival. In addition to an exhibition of his sculpture, he was tasked with creating Encore, a 180-foot mural for the festival’s formal al fresco dinner dance.

Core channeled the knockdown, drag-out energy he’d experienced during New Orleans’ Mardi Gras season when ball decor and costumes were conjured in a matter of days to transform the Louisiana city into a magical kingdom of pre-Lenten mirth.

In eight days, with Schubert blaring to inspire his artistic expression, Core painted a series of large faces, in ten-foot sections in his South London studio.

Images of the Henley Arts Festival mural with permission of the Philip Core estate.

“Writers are always selling somebody out.”

- Joan Dideon

In London, as a critic and a writer, Core earned a steady income and growing fame as a person whose opinion mattered. An encyclopedic knowledge of lesser-known figures of pre-WWII century culture landed him a gig as a commentator on the BBC Radio 4 Kaleidoscope.

His keen observations of the foibles of human nature popped up in Harpers & Queen. As the photography critic and obituary writer for The Independent, he eulogized many luminaries. Some he wrote in advance, obits that the newspaper would file away for future use – like those for Jean-Michael Basquiat (1988) and Robert Mapplethorpe (1989) and Nureyev, who died four years after Core.

Core had maintained a 20-year friendship with Nureyev, and the eulogy he wrote for his friend illustrates Core’s mastery at capturing the essence of his subjects:

“His slant eyes, the same as those of countless generations who had crossed the Russian steppes in seas of blood or wastes of cold; his broad hips and footballer's legs, trained in the Russian manner by slow repetitive movements to an incredible elasticity; his flat masculine hands, reaching like a child's in a pleading gesture he fused with any choreography; his feet which never stop…”

Don’t you just love those long afternoons in New Orleans when an hour isn’t just an hour-

but a little piece of eternity dropped into your hands.”

– Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire

In October 1979 Philip Core returned to New Orleans with an air of English sophistication and an eye to capture the visiting foreign sailors enjoying leave in the French Quarter. The twenty-eight-year-old was waltzed about town by his ceaselessly devoted mother. Core’s exhibition of cut-outs and paintings of literary celebrities at the Contemporary Arts Center was the must-see happening that Halloween season. From the Tom of Finland Foundation archive with permission from the Philip Core estate.

Book cover of The Male Nude. In 1985 New Orleans’ papers were abuzz with the news that Edward Lucie-Smith, the noted British curator and broadcaster, included works by two local artists, Philip Core and George Dureau, in his lavishly illustrated book, The Male Nude: A Modern View.

New Orleans’ readers learned (October 3, 1980, Times Picayune) that the August 1980 issue of British Vogue featured Philip Core’s full-page portrait of Marcel Proust, a popular figure in his paintings, dining on madeleines at London’s Ritz.

By Boxing Day, 1981 Core’s visits to his mother, Lucy, were written about in the local paper as if he were visiting royalty. (By then, his parents maintained separate residences but shared lunch and spirited dialogue every day. His younger siblings, Marguerite and Mason, had left New Orleans for school and careers. )

Lucy Core held court in genteel poverty in what the paper described as a “Carondelet Street carriage house.” There, the sagging seats of its chairs were amply augmented by stacks of well-thumbed magazines. Guests were a ragtag assortment of grande dames, writers and church friends. Presiding over his mother’s Merrie Olde English tea parties was Philip’s life-size cutout of Radcliffe Hall, author of Well of Loneliness.

“In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.”

George Orwell, “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (1949)

Rainbow plaque marking the location of protests against Section 28 in Victoria Gardens, Leeds, image Wikapedia, Creative Commons

In 1988, amid an AIDS-inspired backlash against homosexuals, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Party adopted Section 28, a law that prohibited local authorities from promoting homosexuality. No one was ever prosecuted under the law, but it achieved its goal of making local authorities cautious about funding material or events dealing with homosexual issues.

As a result of Section 28, many local authorities were reluctant to grant public space to gay and lesbian organizations or to host LGBT publications and art in their libraries and galleries. At the same time, however, Section 28 incited the British gay and lesbian movement into action.

Section 28 may be said to have made gay activists out of people who might never have come out. It also inspired prominent gay men and lesbians to form the Stonewall Group, Britain's first major lesbian and gay rights lobbying organization.

Other organizations, including the group OutRage!, were formed to combat the legislation and to agitate for its repeal. The largest political demonstrations on behalf of gay and lesbian rights in British history were motivated by Section 28.

Since the prohibition extended to banning gay-themed books, films, and artwork in libraries and schools, a group called The Arts Lobby countered that Section 28 attacked literature, art and theater, as well as an entire segment of the citizenry. When Core’s West End gallery dropped him for being “too gay,” he joined The Arts Lobby. This group of prominent actors and artists – both gay and straight – included Judi Dench, Patrick Stewart, John Thaw, and Gary Oldman.

Cut-outs by Philip Core, photo courtesy Arthur Roger

The press sat up and took notice when Philip Core smashed a statue of Michelangelo’s David at the Art Lobby’s press conference on Monday, January 25, 1988. Two days later, during a debate on Radio 3, the noted actor Ian McKellan introduced himself publicly as a gay man and an anti-Section 28 activist. On the fifth of June (1988), The Arts Lobby hosted the star-studded theatrical gala “Before the Act” at London's Piccadilly Theatre to protest the assault on gay rights.

Unfortunately, support for Section 28 was fueled by fears about AIDS.

In March 1986, the BBC had broadcast “Aids: A Strange and Deadly Virus” as part of its Horizon series. In April 1987, Princess Diana opened the AIDS ward at Middlesex Hospital.

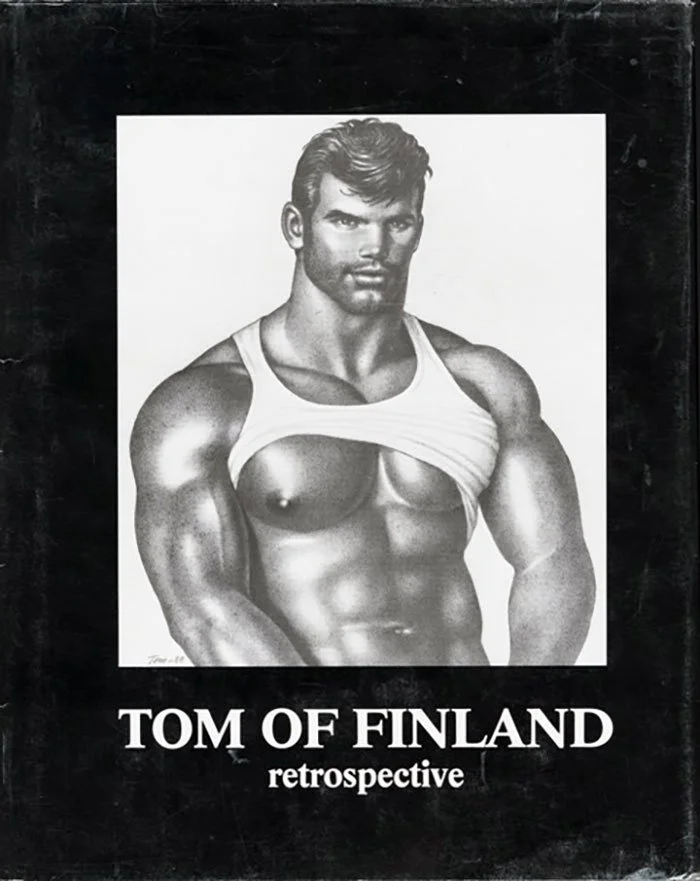

Tom of Finland Retrospective book cover, 1988 Over four decades, Touko Valio Laaksonen, known professionally as Tom of Finland, produced more than 3500 illustrations of homoerotic “beefsteak” for the male homosexual market: sexy bikers, sailors, construction workers, etc. in various stages of undress. In 1984, the Tom of Finland Foundation was established to collect and preserve homoerotic artwork. Today more than 500 works and documents of Philip Core are contained in the archives of the Tom of Finland Foundation.

That same year, British Health Services delivered a pamphlet about the disease to every household in the UK. Some cemeteries refused to bury men who had died from it in fear their bodies would contaminate the water supply. AIDS hysteria empowered Section 28 to class homosexuals as pariahs.

Tragically, Philip Core was battling more than censorship and discrimination. Those closest to him eventually learned that he had AIDS. Once a trendsetter of “shamelessness,” Core became a warrior for safe sex, warning about this catastrophic “accident of history.”

With unflinching urgency, Core produced two major public exhibitions in violation of Section 28: “Clausetrophobia: Philip Core 1973-1988” at the Waterman’s Art Center in Brentford and “Sixteen Positions Old & New” at the Old Bull Arts Centre in Barnet.

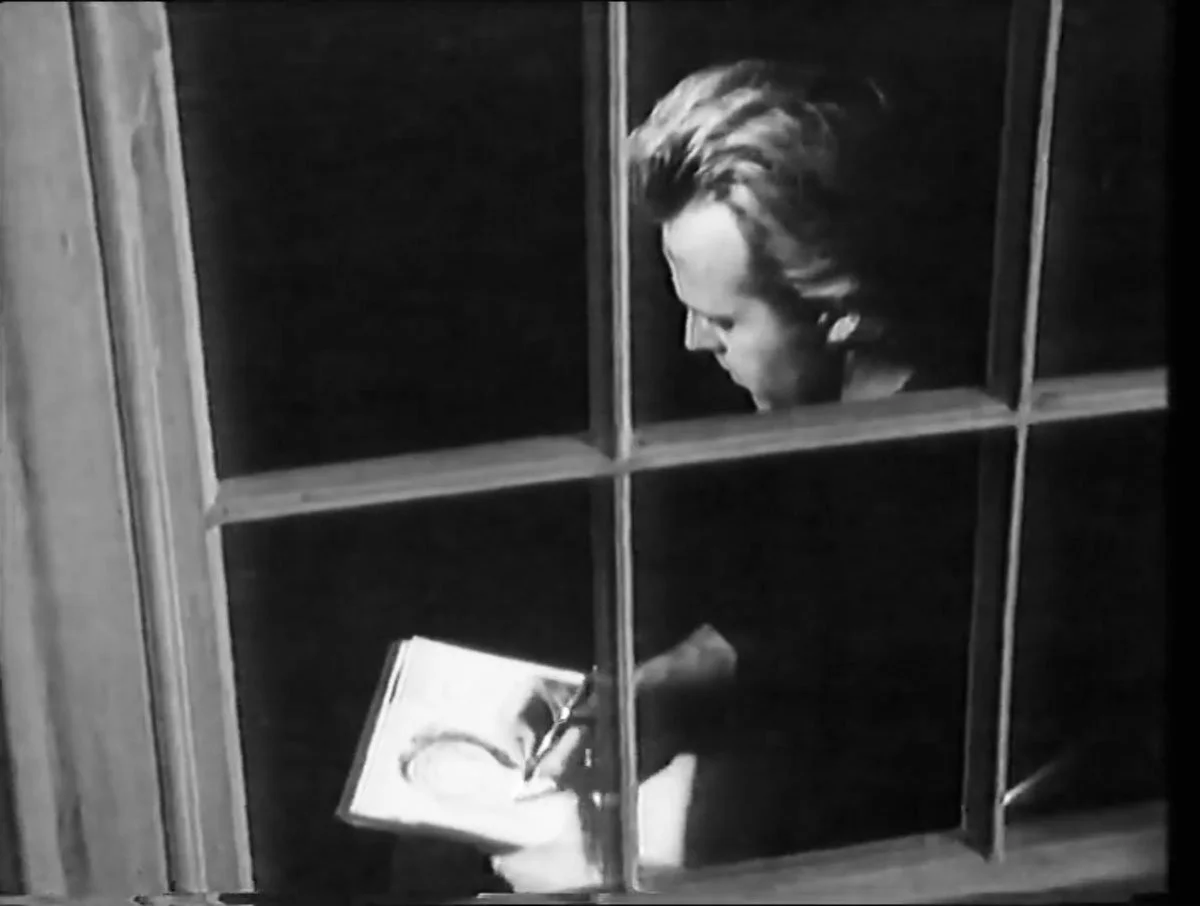

In April 1988, Philip Core returned to New Orleans for what would be the final time. While there, he obtained a personally inscribed copy of Tom of Finland, a Retrospective. He mailed it back to his London studio with photographic images, slides and drawings of men engaged in sex acts, created as studies for his two previous English exhibitions.

The contents fit the definition of obscenity: “repulsive, filthy, loathsome or lewd.” In London, the Royal Mail Customs seized this package and informed Core that the contents would be burned.

To Core, appealing the censorship was a hill worth dying on. He filed suit against the Royal Mail, determined to shed light on the hypocrisy of censorship.

New Orleans’ art dealer Arthur Roger with one of Core’s boxing works. Roger, who represented Core in New Orleans, is working with Core’s family and friends in London, to ensure his legacy lives on through exhibitions. Today, more than 500 of Core’s works are housed in the Tom of Finland Foundation Archive. Image courtesy Arthur Roger.

Untitled painting by Philip Core, image courtesy Arthur Roger

“There are occasions when it pays better to fight and be beaten, than not to fight at all.”

-George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

Core did not protest alone. In June of 1989, after the seizure of his package was made public, the legal department of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs Service (HMRCS) received letters of protest from directors at the Tate and the Victoria and Albert museums – as well as an impressive array of other cultural luminaries who were members of The Arts Lobby. Specifically, they defended Core’s right to his own intellectual property.

Philip Core self-portrait, 1984, from the book Philip Core Paintings, 1975 - 1985. With permission of the Philip Core estate.

On November 9, 1989, Philip Core left his deathbed to appear in London’s Wells Street Magistrates Court. Attired in a borrowed blue Issey Miyake coat, he argued for the return of his property.

“I think it is outrageous that someone who doesn’t know me or my work should be able to dictate what I can and can’t use in my art,” he said.

Core succeeded in his mission of raising awareness. London’s “The Sunday Correspondent” (November 12, 1989) featured an article, “Core and ‘hard porn’: Louisa Buck on an artist’s fight against censoring gays.”

This article appeared on the day he died, three days after his court appearance.

The case was dismissed after his death from AIDS at London’s Westminster Hospital, just a few blocks from the court. He was thirty-eight.

“Freedom is the greatest single reward,” wrote Core in his poignant 1988 artist statement. “As an articulate, gay painter in a foreign country I have always felt myself blessed with an enviable freedom: to work at what I love, to ignore habits of class or social usage where they impede human contact, to look in my own way at whatever strikes me as new or different, and to present my view of things as I choose.”

Core concluded, “I am not a great artist, only someone who loves painting, drawing and making things with his hands above all else; someone who has by some curious gift of heredity, became possessed of articulacy and intransigence in equal degree; someone who knows what they love and feels no shame about it.”

Today, Marguerite and Mason Core continue to preserve as many of their older brother’s works as they can locate with the assistance of the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles.